even-though-im-free-suu-kyi-mw19-collection

Aung San Suu Kyi, leader of the opposition party, the National League for Democracy, was arrested for the first time in July 1989. She has been detained on three separate occasions and has spent more than 15 years under house arrest in Rangoon. Released from her latest sentence in November 2010, she continues to work to achieve democracy and national reconciliation in Burma in spite of continued threats and oppression from the ruling military regime.

On her hand is written the name of Soe Min Min, a member of the National League for Democracy who was arrested in 2008 for praying at Shwedagon Pagoda for the release of Aung San Suu Kyi. He is serving a nine year sentence at Insein prison.

Update: Soe Min Min was released from Insein prison according to a conditional amnesty announced by the Burmese regime on January 12, 2012.

even-though-im-free-u-tin-oo-mw19-collection

U Tin Oo, vice-chairman of the National League for Democracy, has spent more than 17 years in prison and under house arrest at his home in Rangoon. The former commander-in-chief of Burma’s armed forces, he was first arrested in 1976 and charged with high treason by General Ne Win, chairman of the then ruling Burma Socialist Program Party. U Tin Oo has since been arrested three times and was released from his latest sentence of house arrest in February 2010. At 80 years old, he continues to play a significant role in the struggle for democracy.

On his hand is written the name of Aung Zaw Oo, who was arrested in 2008 for promoting human rights, working with labor unions, and for what the regime describes as “illegal association” with outlawed organizations in exile. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison but was released in October 2011 under a general amnesty.

even-though-im-free-maw-gyi-mw19-collection

Maw Gyi is a former member of the Tri-Color student group that provided security to Aung San Suu Kyi. He was arrested in July 1989 in Aung San Suu Kyi’s home along with 40 members of the National League for Democracy. He was detained for three years until March 1992 when he was finally brought before a military court and sentenced to eight years imprisonment with hard labor. Released in 1992 under a general amnesty, he fled Burma and now lives in Tokyo.

On his hand is written the name of Thein Lwin, who was arrested in November 2008 for being part of a group of more than 1,000 people who were demonstrating outside the east gate of Shwedagon Pagoda during the “Saffron Revolution” in September 2007. He is currently serving a three year sentence in Insein prison.

even-though-im-free-thandar-oo-mw19-collection

Thandar Oo was arrested and jailed for her involvement in the student demonstrations in Rangoon in December 1996. She served six years of a seven year sentence in the notorious Insein prison. She continued her activism after her release and was forced to flee Burma with her husband in 2007 when she was threatened with re-arrest. She currently lives with her husband who is also a former political prisoner, in Mae Sot on the Thai-Burma border.

On her hand is written the name of Nilar Thein, who participated in the 1988 mass uprisings when she was a high school student and was first jailed in 1991. She was jailed again in 1996 for leading student demonstrations and served nine years. Together with her husband Kyaw Min Yu, she is a leader of the 88 Generation Students and in August 2007 helped organize peaceful demonstrations against the military regime. As a result, she was forced into hiding for more than a year before she was caught in September 2008. She was sentenced to 65 years and is currently detained in Thayet prison.

even-though-im-free-u-thet-mhu-mw19-collection

Thet Mhu, a former member of the student organization Bagatha and the All Burma Student Democratic Front (ABSDF), was arrested in 1990 and sentenced to seven years in prison for his role in student demonstrations during the mass uprising in 1988 and his association with illegal organizations. He spent more than five years in Insein and Tharawaddy prisons before being released in 1996. He now lives in New York.

On his hand is written the name of Yan Naing, a leading member of the All Burma Federation of Student Unions (ABFSU) who was arrested in 2004 and sentenced to 22 years in prison for issuing a statement demanding political dialogue and the release of all political prisoners. He is currently being held in Insein prison.

even-though-im-free-htein-lin-mw19-collection

Htein Lin, a former student at Rangoon University, fled to the India-Burma border in 1988 where he joined the All Burma Students’ Democratic Front (ABSDF). Years later he returned to Rangoon where, rather than continue his law studies, he decided to work as an artist and comic film actor. In 1998, he was arrested and sentenced to 7 years imprisonment, charged on the basis of an intercepted letter on which his name was listed as a potential activist. He fled Burma and now lives in the United Kingdom.

On his hand is written the name of Zaganar, Burma’s most famous comedian, actor, and film director. Previously imprisoned several times for his political activities, he was arrested in June 2008 and sentenced to 35 years for delivering aid to survivors of Cyclone Nargis and talking to foreign journalists about the government’s lack of action. He was released from Myitkyina prison in October 2011 under a general amnesty.

even-though-im-free-tun-lin-kyaw-mw19-collection

Tun Lin Kyaw is a former member of the Tri-Color student group and lived in Aung San Suu Kyi’s compound from an early age after his parents died. In 2004, he performed a solo protest outside city hall in Rangoon, holding a placard demanding the release of Aung San Suu Kyi and all political prisoners. He was arrested and spent three years in Insein prison. The brutal torture he suffered from the prison guards led to the removal of half of his lung. He fled Burma in 2009 and is currently in Umpiem Mai refugee camp on the Thai-Burma border awaiting resettlement.

On his hand is written the name of Aung Aung Oo, a member of the National League for Democracy and student friend of Tun Lin Kyaw who was arrested in March 2006 for distributing political pamphlets. He is currently serving a 14-year sentence in Insein prison.

even-though-im-free-u-zawana-mw19-collection

U Zawana was arrested in 1993 after meeting with UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights Yozo Yokota and informing him of the dire human rights situation in Burma. He was sentenced to 29 years in jail. Upon his release in 2009, U Zawana was forbidden by the authorities to return to the monkhood and was forced to flee Burma in November 2009. He currently lives on the Thai-Burma border.

On his hand is written the name of U Pyinnyar Wuntha, a colleague of U Zawana and a fellow monk currently being held in Insein prison.

even-though-im-free-grid-mw19-collection

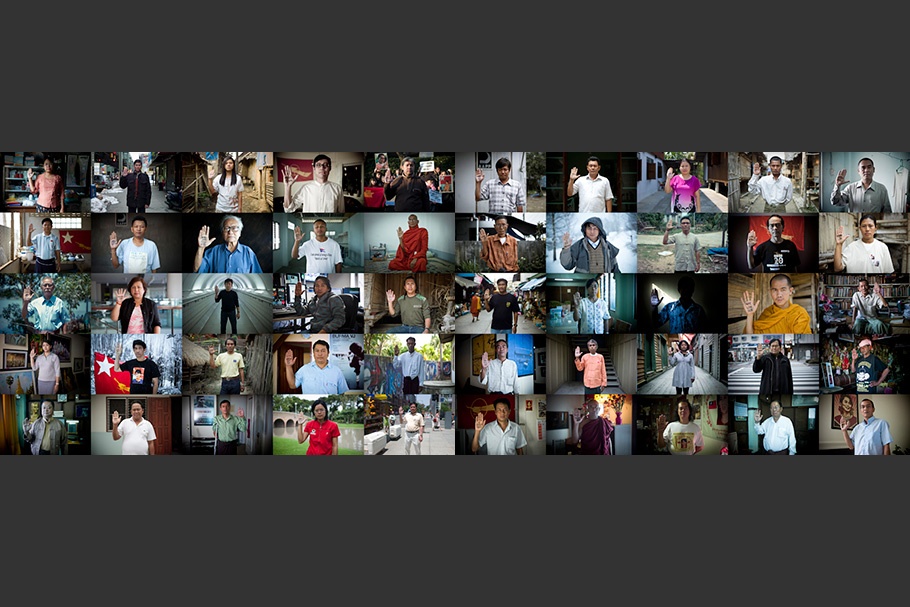

Even Though I’m Free, I Am Not, 2008-2011

Composite grid of 50 portraits of Burmese political dissidents

James Mackay is a documentary photographer based in Southeast Asia and the United Kingdom. He graduated from Central Saint Martins College of Art & Design in London and has worked extensively, often undercover, in Burma and its border regions documenting humanitarian and political issues in the militarily controlled country. Working in close collaboration with exiled Burmese organizations, the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) and the Democratic Voice of Burma, as well as through underground networks both inside and outside of Burma, Mackay has been undertaking a number of long-term projects documenting the democracy movement, political dissidents, human rights defenders, and in particular the issue of Burma’s political prisoners.

His work has been featured in films, books, and a number of leading newspapers and magazines including the New York Times, the Independent, the Observer, the Guardian, the Bangkok Post, Irrawaddy, Vogue Japan, British Vogue, and Dazed & Confused. He has partnered with Amnesty International, exhibited in galleries in Bangkok, London, and New York, and received several awards.

His work on Burma’s political prisoners, Abhaya: Burma’s Fearlessness, features a foreword by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and was published in November 2011.

James Mackay

Burma—A country ruled by fear where torture is state policy and its prison system is one of the darkest hells on earth.

In 1962, a military coup against Burma’s democratically elected government brought in a succession of some of the world’s most brutal military regimes. Since then, thousands of people have been arrested, tortured, and jailed for their political beliefs and for daring to defy the dictators who tolerate no form of dissent or opposition. The struggle for democracy in Burma has been a long and often bloody one, led since 1962 by university student groups and joined in 1988 by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy. Numerous uprisings in each decade have provided brief signs of hope, but have also resulted in the incarceration of thousands of determined and courageous Burmese who have called for change.

From distributing pamphlets to participating in a peaceful demonstration, almost any democratic activity in Burma can prompt the regime to deem people as threats to its power and result in arbitrary detention. Even after they are released, former political prisoners continue to be harassed by authorities, forcing many advocates for democracy to flee the country for fear of rearrest. Burma’s borders and its many refugee camps are awash with political dissidents. As of October 2011, there were more than 2,000 political prisoners in Burma who represent a full range of professions, ages, and genders.

Over the past three years, I have traveled the world photographing more than 250 former political prisoners who have come together to raise awareness for their colleagues still suffering in jail. This project is an attempt to document their stories and bring greater attention to the issue. I also aim to understand how and why the regime chooses to operate in this fashion and how the world continues to show indifference.

In my experience, there is an inextricable bond between political prisoners. I have tried to highlight this relationship by using photography to show how former political prisoners feel tied to their colleagues who continue to suffer in prison. Spending time with former political prisoners around the world is heart wrenching. But the abundance of dignity, determination, and courage displayed by those who remain in prison and those who were once there has inspired me to carry out this work. To have suffered such inhumanity yet remain so calm defies logic. It was this serenity that inspired me to explore how Buddhism, which is the common religion among many former and current prisoners, provides an important link between the worlds inside and outside prison walls. The Buddhist Abhaya Mudra hand symbol means fearlessness. In an act of defiant protest, those who are no longer in prison have written the name of an imprisoned colleague on the palm of their hand.

This project includes many photographs taken inside Burma which cannot be shown, and many of the project participants have taken huge risks by agreeing to be involved. The fact that they have taken and faced these risks for much of their lives puts things in perspective for many of us who lead less perilous lives. Working in Burma is difficult and dangerous. Without underground networks both inside and outside the country this project would not have been possible. Some people in Burma with whom I have worked are now in jail as political prisoners, bringing a personal aspect to the work that I could never have imagined nor have ever wished for. But these are not my stories. These are the stories of advocates for democracy and justice who refuse to be silenced.

The unconditional release of Burma’s political prisoners is an issue that is fundamental to the future of the country. It is a demand made by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy that is echoed by governments and human rights organizations across the world. There can be no national reconciliation in Burma as long as there are political prisoners. How can there be, when so many of the people who were chosen to lead the country and so many of those who can help shape its future—doctors, lawyers, teachers—are still in prison? Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has said, “Please use your freedom to promote ours.” The future of Burma lies in its people.

—James Mackay, November 2011

Burma Project/Southeast Asia Initiative

The Burma Project was established in 1994 to increase international awareness of conditions in Burma and help the country make the transition from a closed to an open society. The Burma Project/Southeast Asia Initiative has helped activists call attention to denial of fundamental freedoms in Burma, military attacks on civilians, and the imprisonment of political dissidents. Burma’s military government prompted hopes for fundamental reform, including the release of all political prisoners, when it lifted some restrictions on the media and internet in mid-2011. By October, however, the government had only released 200 political prisoners and Burma Project grantees continue to advocate for unrestricted release of all political prisoners.