kenyas-nubians-elders-mw19-collection

Greg Constantine

Nubian elders sit in a soda shop in the Makina section of Kibera. December 2008.

Despite having lived in Kenya for over 100 years, the Nubian community has historically been shorn of recognition. Since Kenya's independence, they have been denied many social, civil, and economic rights.

kenyas-nubians-coffee-table-mw19-collection

Greg Constantine

In 1917, the British designated 4,197 acres of land for the Nubians to settle on as compensation for not being able to return to Sudan. The Nubians called the land Kibra, or land of forest. All of their claims to the land of Kibra have been denied by Kenyan authorities and Kibra turned into Kibera, one of the largest slums in Africa.

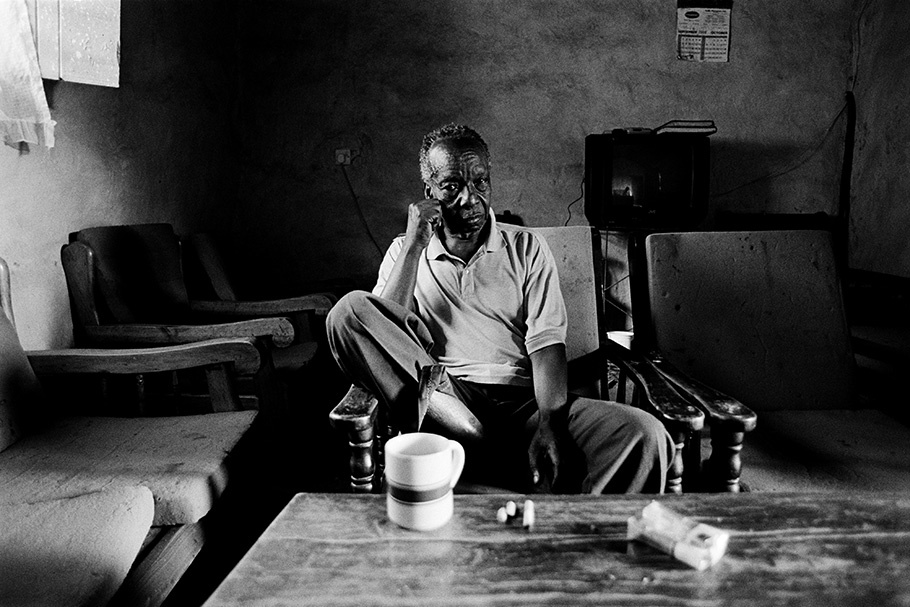

This 79-year-old Nubian man once lived on a large plot of land in the Lomle section of Kibera but in 1978 developers came, destroyed his family's home, and forced them to move to another section of Kibera. "We're being squeezed into extinction," he says. December 2008.

kenyas-nubians-shoes-mw19-collection

Greg Constantine

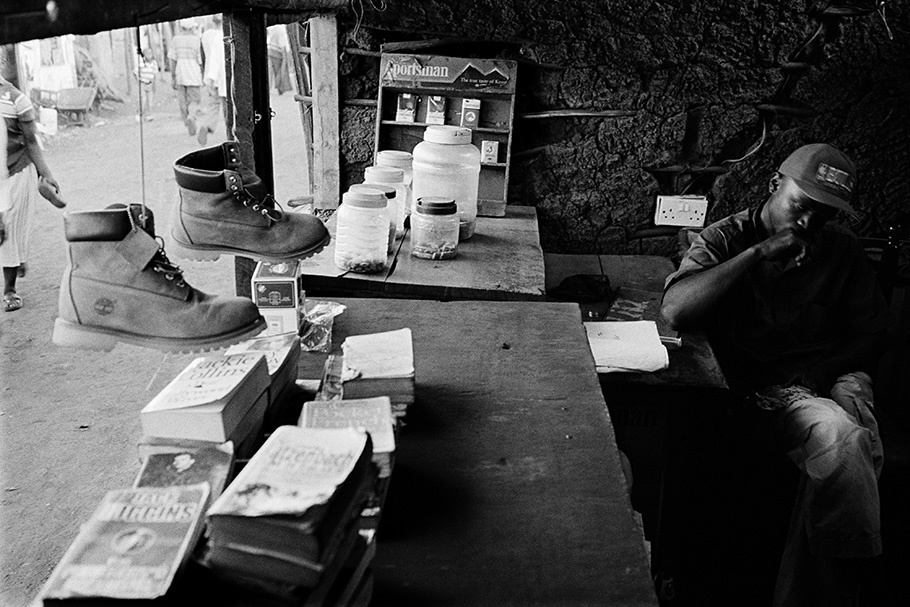

Most Nubian youth, like this young man, find they are limited to working odd jobs in Kibera. December 2008.

Nubian youth must go through a process called “vetting” in order to be issued a National ID card. Nubians are one of the only people in Kenya to be vetted. Nubian youth often have to wait months before they are issued an ID card. While people from larger tribes hold important positions in the private and public sectors in Kenya, few, if any, Nubians have positions significant enough to help influence their community's development and voice in society.

kenyas-nubians-houses-mw19-collection

Greg Constantine

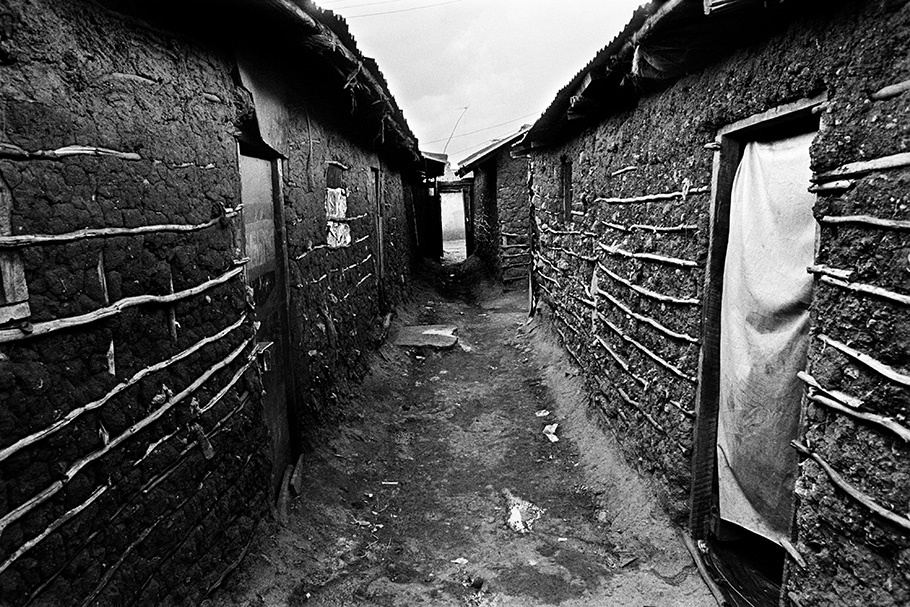

In 1955 the total population of the Nubian village of Kibra was 3,000 people. Nubian families once had spacious plots of land called shambas. Today hundreds of thousands of people live in dilapidated rooms and houses in Kibera. Nubian homes are considered temporary structures, even though some Nubian homes are almost 100 years old. November 2008.

kenyas-nubians-woman-mw19-collection

Greg Constantine

A Nubian woman and children stand in front of one of the oldest Nubian buildings in Kibera, called Nyumba Kumbya. Nubians hid Jomo Kenyatta and other Kikuyu freedom fighters from the British in this building during the Mau Mau rebellion. December 2008.

Rulings by the Kenya government after independence in 1963, changed Kibera's status into an “unauthorized settlement,” rendering the inhabitants of Kibera, including the Nubians, as squatters.

kenyas-nubians-family-mw19-collection

Greg Constantine

This family has lived in the Laini Saba area of Kibera for over 100 years. Laini Saba translates into “firing range” and was an area where Nubian soldiers from the King's African Rifles trained. Dozens of Nubian families once lived in the area. Now only a handful of Nubian families remain.

"Kibera wasn't always like this,” said Toma (left). “To be from Kibera meant that you were Nubian. Now, to be from Kibera means that you are from a slum." December 2008.

kenyas-nubians-photo-mw19-collection

Greg Constantine

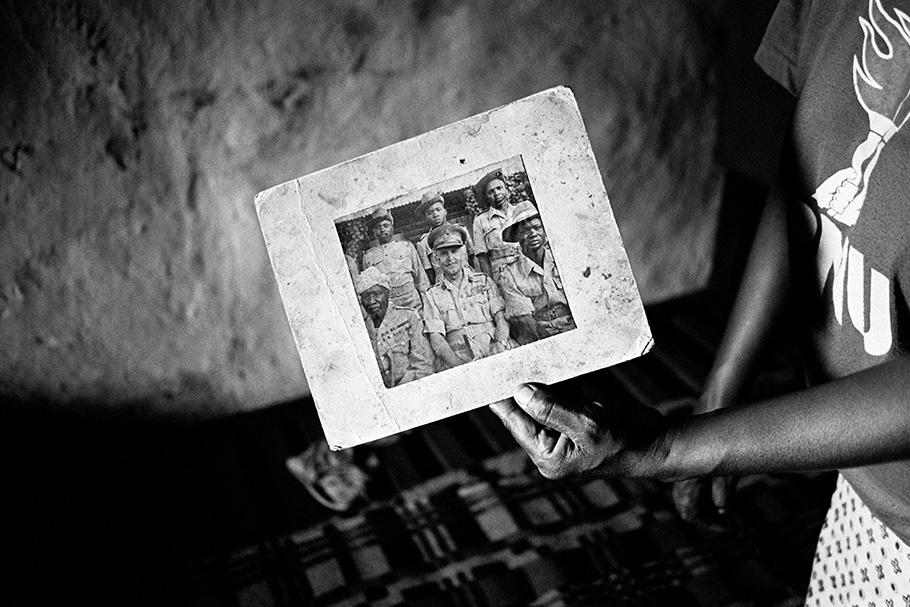

A woman holds a photo of her grandfather who served in the King's African Rifles. November 2008.

Nubians from Sudan were conscripted into the British Army in the 1880s and brought to Kenya in the early 1900s. The Nubians fought for the British in East Africa during World War I and World War II in a military unit called the King's African Rifles.

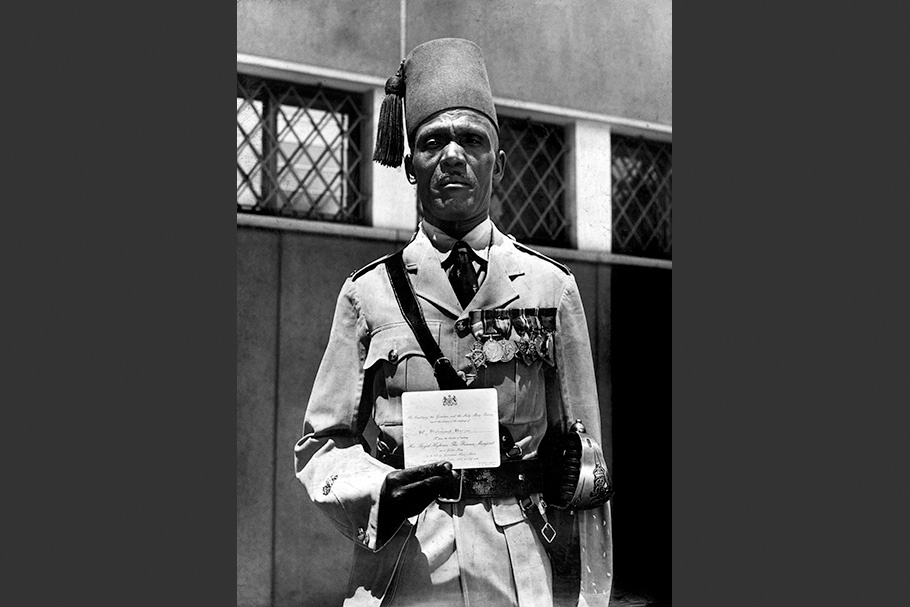

kenyas-nubians-officer-mw19-collection

Photographer unknown

A Nubian officer of the King's African Rifles holds his invitation to a garden party at the Government House of Nairobi in honor of HRH Princess Margaret of England. Nubians were recognized and invited to such events when members of the British Royal family visited Kenya. 1956.

kenyas-nubians-three-women-mw19-collection

Photographer unknown

Nubian women wearing traditional dress called gurbaba. 1947.

kenyas-nubians-family-formal-mw19-collection

Photographer unknown

Nubian family photograph. 1940s.

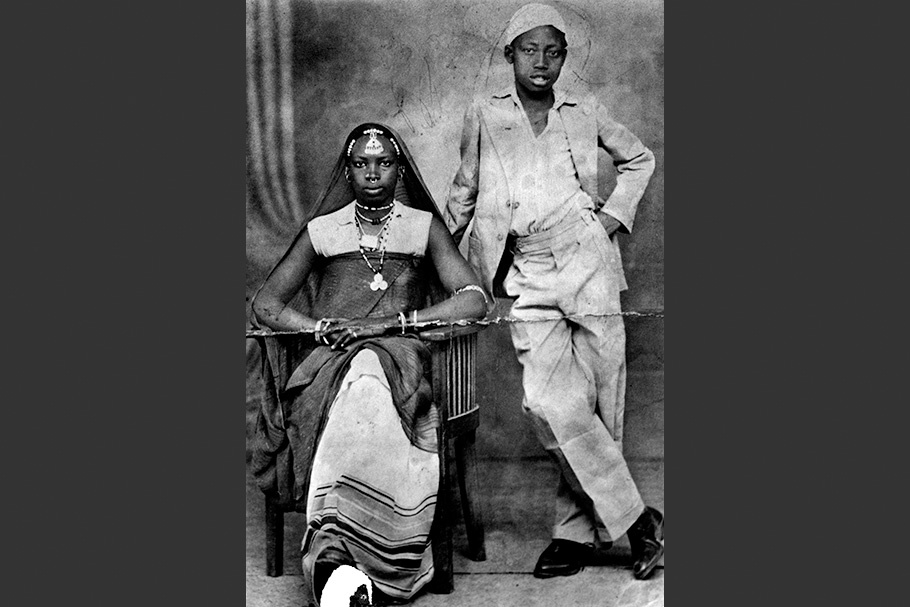

kenyas-nubians-aunt-nephew-mw19-collection

Photographer unknown

Family members (aunt and nephew) pose for a photo after a wedding in Kibera. 1961.

kenyas-nubians-womens-group-mw19-collection

Photographer unknown

The Nubian women’s group Muchumwa welcomed Kenya’s President, Jomo Kenyatta, at the airport whenever the President returned from a trip abroad. 1969.

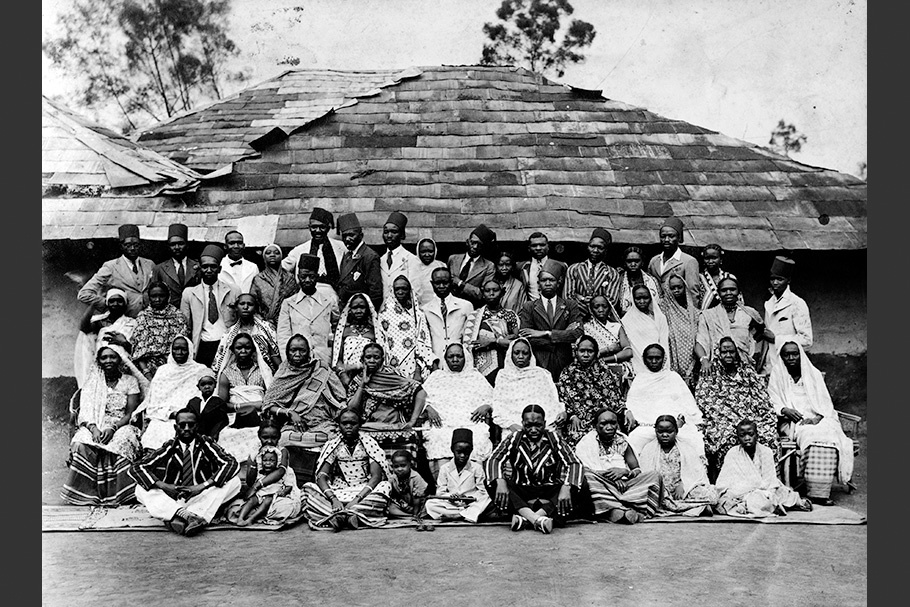

kenyas-nubians-large-group-mw19-collection

Photographer unknown

Family and friends gather in the Makina section of Kibra for a group photograph. 1943.

kenyas-nubians-women-on-grass-mw19-collection

Photographer unknown

Four Nubian women sit on the grass in the Laini Saba area of Kibera, which was once an old shooting range for the King’s African Rifles. 1950s.

Kibera was once called the Nubian village of Kibra. Nubians have lived on the land for over a century. Nubians consider the land to be their heritage and homeland in Kenya. Kibera was once situated among bush, mango trees, and green grass.

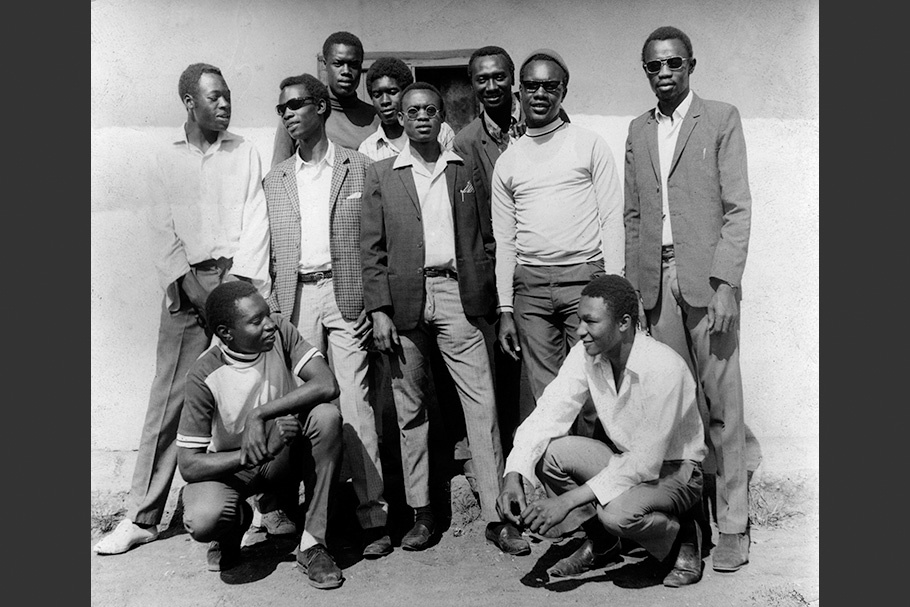

kenyas-nubians-sports-club-mw19-collection

Photographer unknown

Members of the Young Rovers Sports Club, the oldest Nubian youth group in existence. 1960s.

Greg Constantine was born in Carmel, Indiana, and is currently based in Southeast Asia. Since late 2005, he has worked on a long-term project titled Nowhere People, which documents minority groups around the world who have become stateless because governments denied or stripped them of their citizenship.

His work has been recognized by Pictures of the Year International, the National Press Photographers Association’s Best of Photojournalism, Days Japan, the Amnesty International Media Awards in the United Kingdom, and the Human Rights Press Awards in Hong Kong. He has received the Society of Publishers in Asia Award, and the Harry Chapin Media Award for Photojournalism. In 2009, the Asia Society awarded Constantine and four journalists from the International Herald Tribune the Osborn Elliott Prize for Excellence in Journalism on Asia for their work on the aftermath of Cyclone Nargis in Burma.

Constantine is a recipient of a visiting research fellowship from Oxford Brookes University (2008), was a Getty Images Grant for Good finalist (2009), and a recipient of an Open Society’s Culture and Art program Audience Engagement Grant (formerly the Distribution Grant, 2009). He has worked in collaboration with several international organizations, including UNHCR, the World Food Programme, Refugees International, and Médicins Sans Frontières. Constantine’s work has been exhibited in Bangladesh, Cambodia, Kenya, Malaysia, South Korea, Switzerland, Thailand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. His first book, Kenya’s Nubians: Then & Now, was released in fall 2011 and is the first in a series of books from Nowhere People to be published over the next two years. The second book in the series, Exiled to Nowhere: Burma’s Rohingya, is scheduled for release in spring 2012.

Greg Constantine

In the late 1800s, the British Army began incorporating soldiers from the Nuba Mountains in what is now Sudan into its ranks and deployed them to Kenya. During both World Wars, Nubian troops fought for the British in the King’s African Rifles and many carried British colonial passports. Once their service was over, they were given settlements in Kenya, rather than being repatriated. Unable to return to Sudan, the Nubians remained on those settlements, the largest plot of land being just outside Nairobi. The Nubians named this land “Kibra” or “land of forest.”

After Kenyan independence in 1963, most Nubians—in spite of the vital role they played in the history of Kenya and East Africa—were not recognized as citizens of Kenya because of their Sudanese heritage and many became stateless. While many Nubians today have managed to regularize their status as Kenyan citizens, discrimination in access to nationality remains a major problem. Up until the most recent census in mid-2009, the Nubian community was not a formally recognized tribe of Kenya and many Nubians are still unable to fully participate in Kenyan society. The settlement once called “Kibra” is now Kibera and has grown from a community of 3,000 mostly Nubians in 1955, to one of the largest slums in Africa with a population in the hundreds of thousands—many rural migrants—who represent all the major Kenyan ethnic backgrounds. Meanwhile, the Nubians’ claim to this land has still gone unacknowledged. The denial of nationality and documentation such as national IDs and passports, as well as land rights, has been used by successive Kenyan governments to marginalize the Nubian community.

Since late 2005, I have worked on a single, long-term project documenting the impact that the denial of citizenship has on minority communities around the world. In 2008, in collaboration with UNHCR, I traveled to Kenya to create a photo essay about the Nubian community in Kibera. My conversations with Nubians in their homes often resulted in them showing me rare, heirloom photographs that most had never shared with anyone outside of their immediate family.

These archival photographs provided me with a unique historical portrait of the Nubians; a portrait of an empowered and confident community of people with a strong sense of connection to the land where they live. Most people in Kenya—as well as many people outside of the country—have no idea of this history or the various forms of exclusion that Nubians in Kenya currently face on a daily basis.

In 2010 and early 2011, a team of Nubian youth went door-to-door in Kibera asking Nubians to loan their family photographs to this project as a way for individuals to actively participate in telling others about the history of the Nubian community. Juxtaposing the older photos with my recent work makes the costs of statelessness clear by using context and contrast to show what Nubians have had and lost during their time in Kenya. The experience of Nubians in Kenya is one example of what makes statelessness one of the most radical forms of injustice today. Statelessness is a silent form of abuse and exclusion that evades both headlines and the attention of the international community. It is a condition that erases the identities and histories of entire groups of people. It deprives people of opportunities and fundamental rights that are crucial for the self-determination and empowerment of individuals, families, and communities. The perpetrators of statelessness—mostly governments—are not held accountable. This leaves stateless people, like many Nubians, disenfranchised and without access to basic rights such as education, employment, and freedom of movement. These enormous obstacles force them to the margins of society.

This project aims to both highlight the struggles of a community which—as one Nubian elder described it—is “being squeezed into extinction” and celebrate the dynamic and rich heritage of a community that continues to strive for recognition.

—Greg Constantine, November 2011

Open Society Justice Initiative

The Open Society Justice Initiative uses law to protect and empower people around the world. The Justice Initiative’s work on the issue of statelessness addresses a condition that impacts over 12 million people across the globe. Most stateless people lack basic forms of identification, like birth certificates and passports, leaving them vulnerable to arbitrary arrests and unable to move around freely. Statelessness often means they can’t vote, they can’t own property, they can’t get medical care, and they can’t go to school—they live life in the shadows of society. The Justice Initiative is working to eradicate statelessness and bring this global problem the attention it deserves through strategic litigation, advocacy, and research.

Open Society Initiative for Eastern Africa (OSIEA)

The Open Society Initiative for Eastern Africa promotes public participation in democratic governance, the rule of law, and respect for human rights. The Initiative’s work on statelessness issues includes sponsoring events and activities that analyze and develop strategies for combating discrimination and gaining access to citizenship for Nubians living in Kenya.

Kenya’s Nubians: Then & Now website

The Kenya’s Nubians: Then & Now website combines Greg Constantine’s photographs documenting the consequences of statelessness and the denial of citizenship of Nubians in Kenya, with rare historical photographs from Nubians’ personal collections. The archival material that appears on the website was collected in 2010 and 2011 by a team of Nubian youth who went door-to-door in Kibera asking Nubians to loan their family photographs. This community archiving project enabled individuals to actively participate in establishing a visual history of the Nubian community in Kenya. The website was supported by a 2009 Open Society’s Culture and Art program Audience Engagement Grant (formerly called the Distribution Grant).