20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-001

Nigerian and foreign workers on the Amenam Kpono oil platform off the Niger Delta in the Atlantic Ocean. This platform produces 125,000 barrels of oil a day for Total of France and employs approximately 90 percent Nigerians, but few from the Niger Delta.

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-002

In the oil town of Afiesere, local Urohobo people bake "krokpo-garri," or tapioca, in the heat of a gas flare. The town's residents have utilized the gas flares since 1961 when the Shell Petroleum Development Company first opened this flow station. Pollutants from the flares cause serious health problems, shortening the life spans of people working near them.

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-003

Workers subcontracted by Shell Oil Company clean up an oil spill from an abandoned Shell Petroleum Development Company well in Oloibiri, Niger Delta. Wellhead 14, closed in 1977, has been leaking for years; in June of 2004, it spilled over 20,000 barrels of crude oil.

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-004

Drivers wait for work in the tanker park of the PTD (Petroleum Tanker Drivers). As a result of the violence that forced refineries to shut down or curtail production, many of these drivers had been waiting for three months at the park to obtain oil products for delivery throughout Nigeria.

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-005

Trans Amadi Slaughter is the largest slaughterhouse in the delta. They kill thousands of animals a day, roast them, cut them up, and prepare the meat for sale. As fish stocks have dwindled due to pollution from oil and over-fishing, meat is overtaking fish as the main source of protein.

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-006

The NNPC (Nigerian National Petroleum) pipelines run through Okrika near Port Harcourt. Okrika is a troubled area where fishing, once the main form of work, is declining and factional violence over oil is increasing.

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-007

In Uvwie, a local district of Warri, a funeral procession celebrated the life of Roseline Okotie, 63, who had 33 grandchildren. Family members dressed up and marched alongside the colorful burial band.

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-008

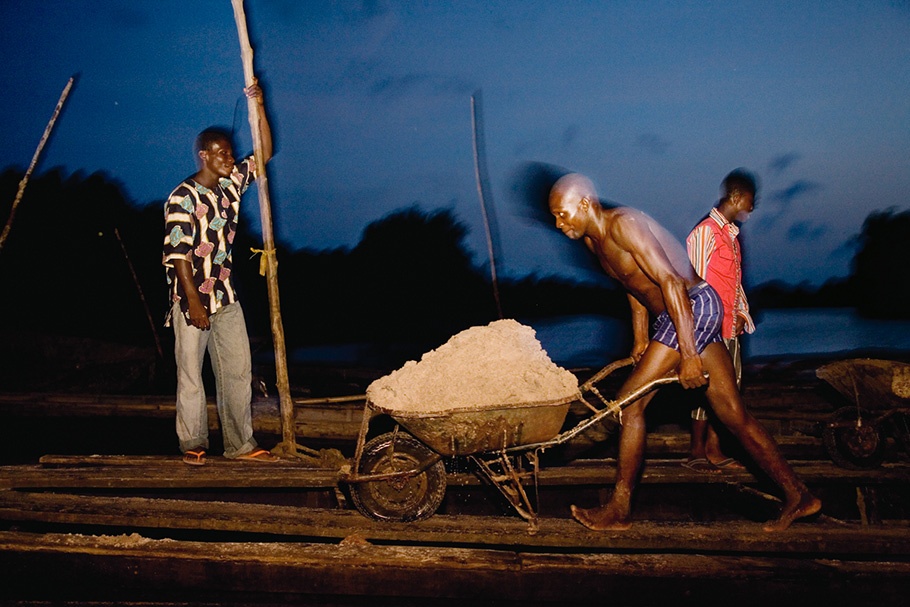

In Ubeji, which is near an NNPC refinery, villagers collect sand from the creeks for sale.

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-009

Men cut wood from mangrove trees in the swamps to use for drying fish. The Mobil Exxon Gas Plant appears in the background, across the water.

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-010

In the fishing village of Finima, women sort through catches of bonga fish, gold fish, and silver fish before taking them to dry and then sell. Pollution caused by the oil companies has lowered the quality and quantity of fish, but the oil companies haven’t helped by hiring unemployed local workers.

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-011

The Cherubim and Seraphim Mount Zion Finima church is an African-Christian church with branches throughout the delta.

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-012

Living conditions in Okrika. Oil leaks and fires along the pipelines have plagued the community.

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-013

The pollution and environmental degradation of the Niger Delta is striking, particularly in the towns and cities where the lack of sanitation is overwhelmingly evident.

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-014

Workers push heavy barrels of gas up front the waterfront into the main market road of Yenagoa.

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-015

Armed militants with MEND (Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta).

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-016

Armed militants with MEND.

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-017

Armed militants with MEND.

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-018

The burial of a MEND fighter killed in an ambush. Nine MEND members had just negotiated the release of a Shell Oil Company worker taken hostage when, returning from the negotiations, Nigerian military boats ambushed and killed all nine as well as the Shell worker.

20080313-kashi-mw14-collection-019

King Nemi Tamunoiyala Oputibeya the 10th of Okrika in the Niger Delta.

Ed Kashi has dedicated his photographic career to documenting the social and political issues that define our times. Since graduating with a degree in photojournalism from Syracuse University in 1979, he has photographed in over 60 countries. His images and essays have appeared in National Geographic, New York Times Magazine, Time, Fortune, GEO, Newsweek, and various other domestic and international publications.

Kashi’s photographs chronicling the negative impact of oil development on the Niger Delta is his 11th major story for National Geographic. His Iraqi/Kurdistan video flipbook, premiering on MSNBC.com, demonstrated Kashi’s innovative approach to photography and filmmaking, garnering a Black Maria Film and Video Festival Award (2007).

With his wife, writer Julie Winokur, Kashi completed an eight-year project, Aging in America: The Years Ahead, which included a traveling exhibition, an award-winning documentary film, a website, and a book. Talking Eyes Media, Kashi and Winokur’s nonprofit multimedia company, has produced a book and traveling exhibition on uninsured Americans called Denied: The Crisis of America’s Uninsured.

Kashi has two books coming out in 2008, Curse of the Black Gold: 50 Years of Oil in the Niger Delta, and THREE, an artist’s monograph of triptychs culled from his more than 25 years of making images.

Ed Kashi

Since my first trip to the Niger Delta in July 2004, with Michael Watts, a Berkeley-based scholar who has studied oil and conflict for over 30 years, I have been obsessed with telling this difficult but profoundly important geopolitical story in a visual way. This exhibition shows the consequences of a half century of oil exploration and production, exposing the reality of oil’s impact and the absence of sustainable development in its wake.

Nigeria is the sixth largest producer of oil in the world—and now one of the major suppliers of U.S. oil in what has been called the scramble for African oil. Virtually all of Nigeria’s oil is pumped from the nine states that make up the Niger Delta in the southeast of the country. Yet the delta remains the poorest region in the nation. Political gangsterism, corruption, and poverty seem to converge there.

Since the first wellhead in 1958, more than $500 billion dollars has been pumped out of the Niger Delta’s fertile grounds. Petroleum production causes devastating pollution from uninterrupted gas flaring and oil spillage. The traditional livelihoods of fishing and agriculture are no longer productive enough to feed the region.

After my first visit with Watts, I returned on my own to the Niger Delta in late 2005 and faced severe restrictions and frustrations. But a year later I went back with a commission from National Geographic, making breakthroughs to areas and subjects that had been virtually impossible before.

One of the most important subjects I photographed was the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta, an armed and formidible militant group responsible for disrupting and shutting down large parts of Nigeria’s oil industry through direct attacks on facilities, the taking of hostages, and the creation of an inhospitable and unsafe environment for the oil production. The struggle for the control of oil creates secrecy and shadows across a landscape of historic exploitation, influential transnational corporations, violence encouraged and supported by politicians, and the turmoil of leaderless groups, gangs, and cults.

The Niger Delta is one of the most difficult places I’ve ever worked. The people are hesitant and suspicious of outsiders, the terrain is tricky with out-of-the-way places only reachable by small boats, and dangers lurk along every road and waterway. In June 2006, while attempting to photograph flow stations in the creeks of Nembe, I was arrested by the Nigerian military. My fixer and I were locked in a room for four harrowing days, our possessions and equipment confiscated. We were released through the great work of family, friends, and colleagues, but others are less fortunate and endure a much longer, more painful incarceration. This event left me even more determined to create a visual body of work to tell the untold story of the Niger Delta.

We must always remain open in our hearts and minds. This is what makes life worth living and allows us the opportunity to witness the unimaginable. I am forever grateful for my chance to work in the Niger Delta, and to attempt to shed some light into its world of shadows.

—Ed Kashi, February 2008