20080313-popa-mw14-collection-001

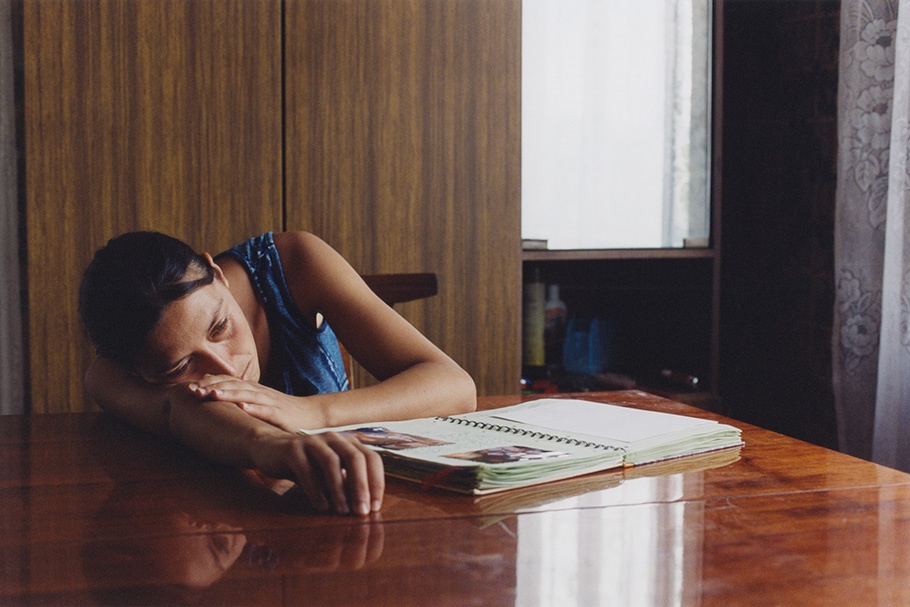

Dalia, 20 years old

Turkish authorities renewed her visa while she was being forced to work as a prostitute.

Born in Romania in 1977, Dana Popa studied advertising and mass communication at the School of Journalism and Mass Communication Studies at the University of Bucharest. She completed her master’s degree in documentary photography and photojournalism at the London College of Communication.

Popa has been based in London as a freelance photographer for the last three years. Her work focuses on contemporary social issues with a special emphasis on human rights.

In 2007, for her series on sex trafficking, she received the Special Jury Prize in the Days Japan International Photojournalism Awards and a Jerwood Photography Award. She has exhibited in the United Kingdom and Luxembourg. Her photographs have been published in Days Japan, Portfolio, D: la Repubblica delle Donne, KK, and Ogoniok.

Dana Popa

Sex trafficking—or forced prostitution—is one of the most profitable illegal businesses in Eastern and Western Europe. Women who survive sex trafficking tell horror stories about being raped and abused. Many of them contract sexually transmitted diseases, including hepatitis and HIV, and suffer emotional and psychological problems.

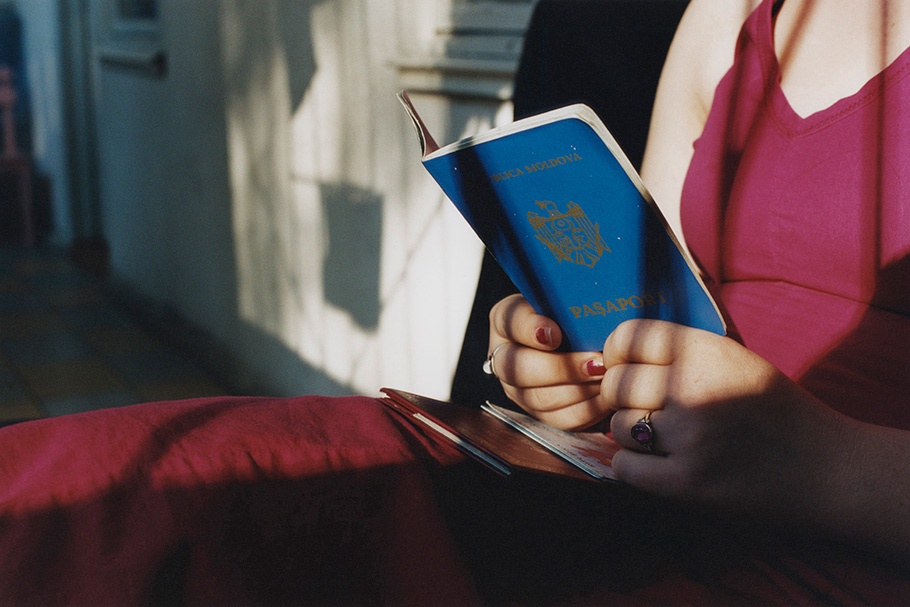

Moldova has turned into a major supplier of women for the sex industries in Albania, the Czech Republic, Dubai, Italy, Romania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) in Moldova has helped hundreds of women return home from these countries.

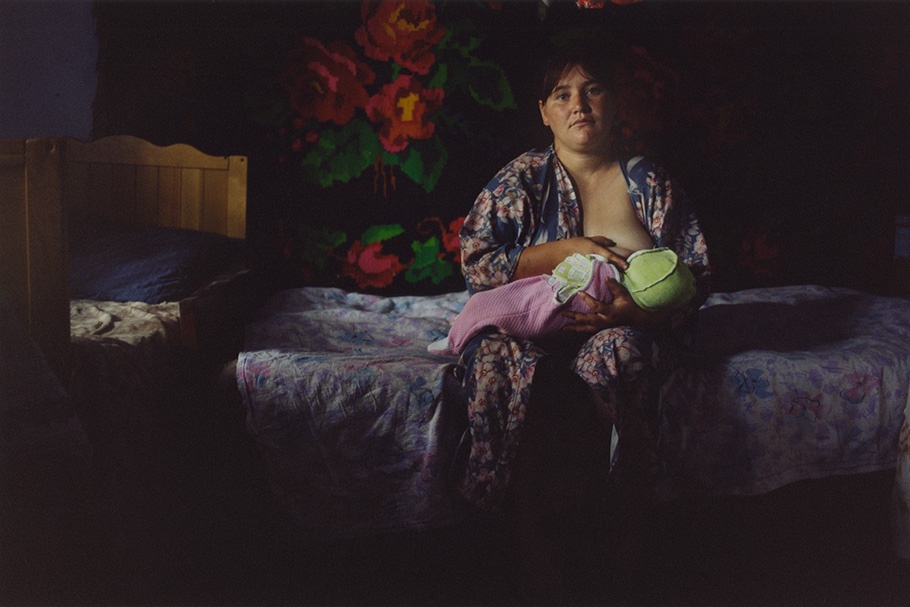

Others have visually documented the work of women inside brothels or on the streets. I chose to depict a different story about the women who were sex trafficked and succeeded in returning to their home country. I wanted to see how they managed to live with the traumas they had experienced in a world that knows nothing about their suffering, how they lived under a huge shadow of fear that a mother or husband might find out and throw them out in the street.

I spent two weeks at the IOM shelter in Moldova, among survivors of sex trafficking who had been assisted in their return to Moldova. Through interviews and discussions, five women began to trust me and felt free to reveal the appalling details of their stories. I carried my camera with me at all times, but I took only a few rolls of film toward the end of my time at the shelter. I wanted to photograph the women in their own environments, in the places to which they returned.

Eventually, I visited 15 women who had been sex trafficked—usually accompanied by a social worker. I explained the reasons for my work in detail to every woman I photographed. I had to be both discreet and protective. These women were still dealing with strong emotional issues; they did not want a stranger intruding into their lives. Polina, a woman from Ukraine, raised her voice when I tried to find out about her: "My story, do you want to hear my story? You have heard it...several times...over and over again."

Ion, the husband of one of the trafficked women, simply said, "I love my wife. It is not her fault that such a terrible thing happened to her. We both decided she could try and earn some good money in Turkey as a vendor at the market. You see, there were only job offers for women. I feel guilty I let her go. But she did nothing wrong and nobody should condemn her." The couple had no problems with me photographing Aurica and showing her face. Others did not want to be identified so I have changed the names of all the women in the photographs.

—Dana Popa, February 2008