20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-001

Humanity Street. New Orleans, LA, 2005.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-002

Clean Shirts.

Tupelo Street, New Orleans, 2006.

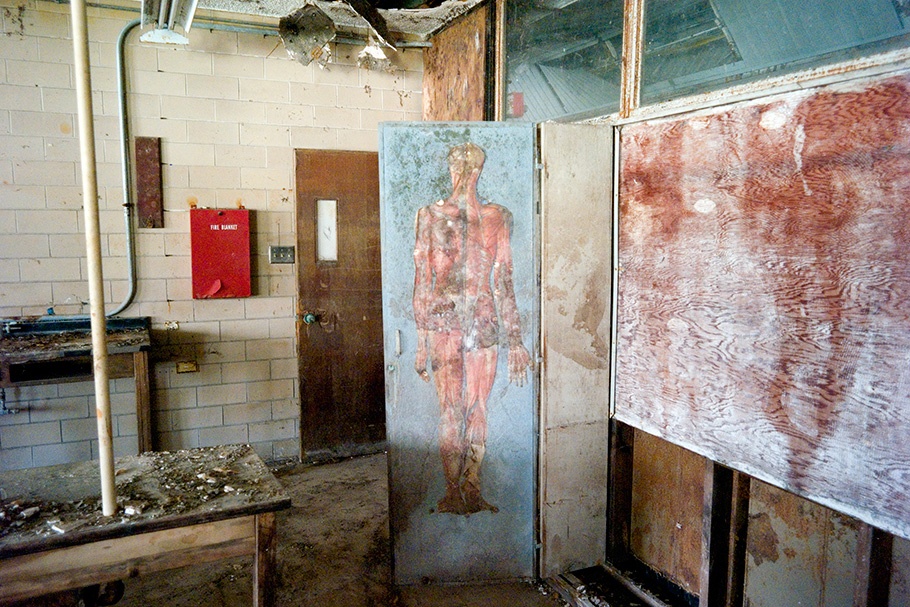

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-003

Science lab, Alfred Lawless High School. Lower Ninth Ward, New Orleans, LA, 2007.

Two years after Katrina, less than half the schools in New Orleans were open.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-004

A church destroyed by Hurricane Katrina is still abandoned two years later.

Lower Ninth Ward, New Orleans, LA, 2007.

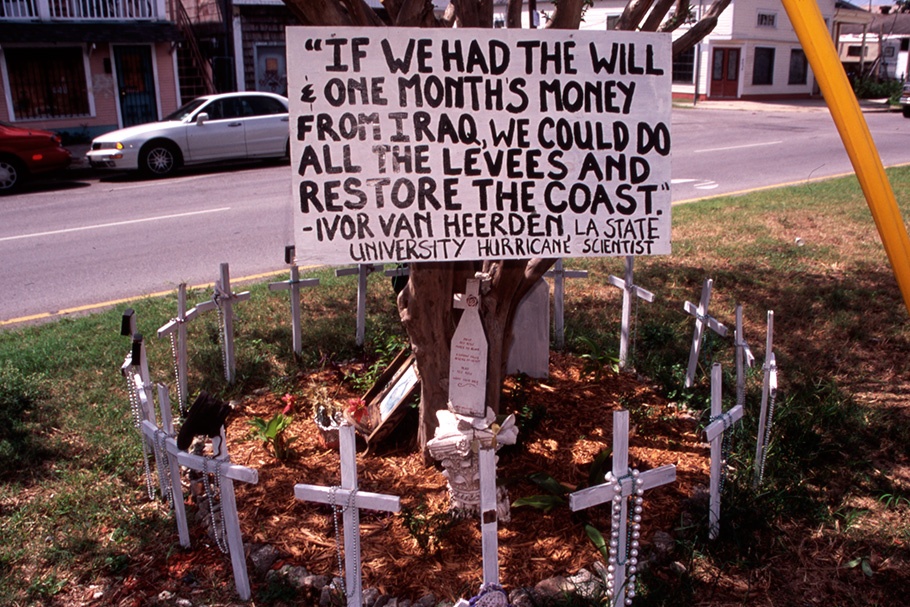

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-005

New Orleans Series #3.

New Orleans, LA, 2006.

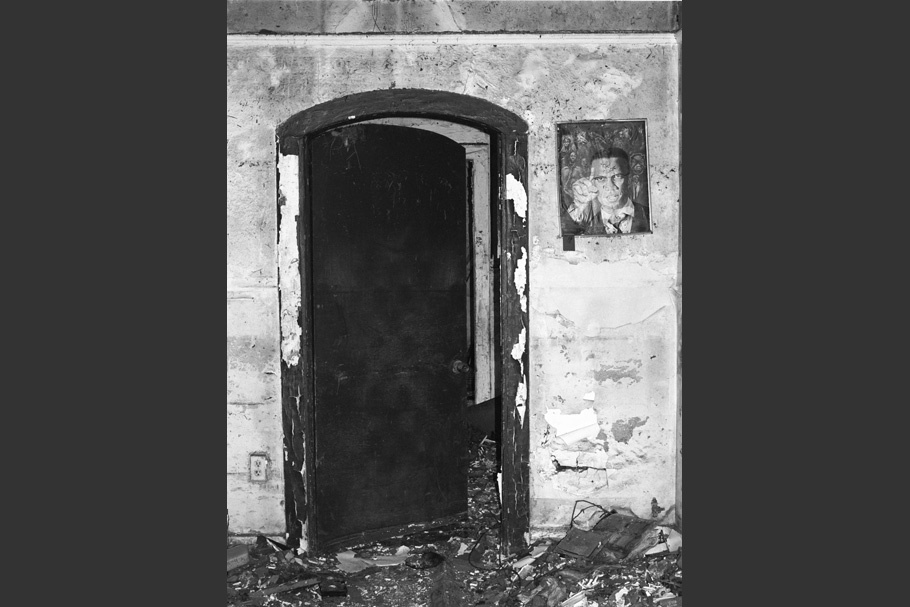

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-006

Malcolm X.

Lower Ninth Ward, New Orleans, May 2007.

A home flooded by Katrina remains damaged, two years later.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-007

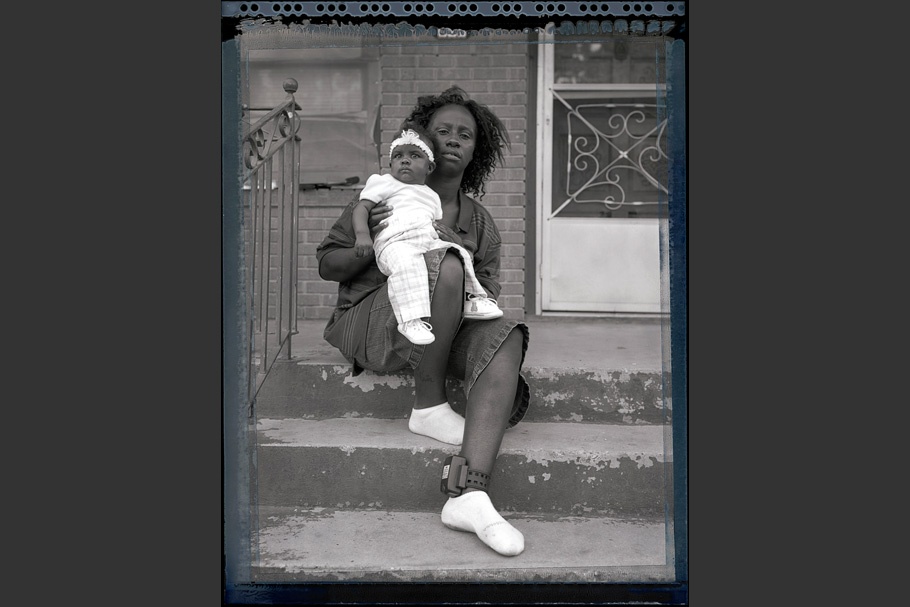

Terry Burton

New Orleans, October 2006.

Burton, 53, suffered from mental illness and lived in his damaged family home in the Lower Ninth Ward with no electricity and giant holes in the floor. On March 8, 2007, members of the National Guard chased Burton into a vacant house after seeing him riding a bike and carrying a hacksaw. When he allegedly pointed a rifle at them, the Guard opened fire and killed him. The rifle turned out to be a BB gun.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-008

Beulah Carey

New Orleans, August 2006.

Carey returned to New Orleans nine months after being evacuated. She is now living in the Holy Angels retirement home on St. Claude Avenue.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-009

Hands That Need Uplifting.

Lower Ninth Ward, New Orleans, August 2006.

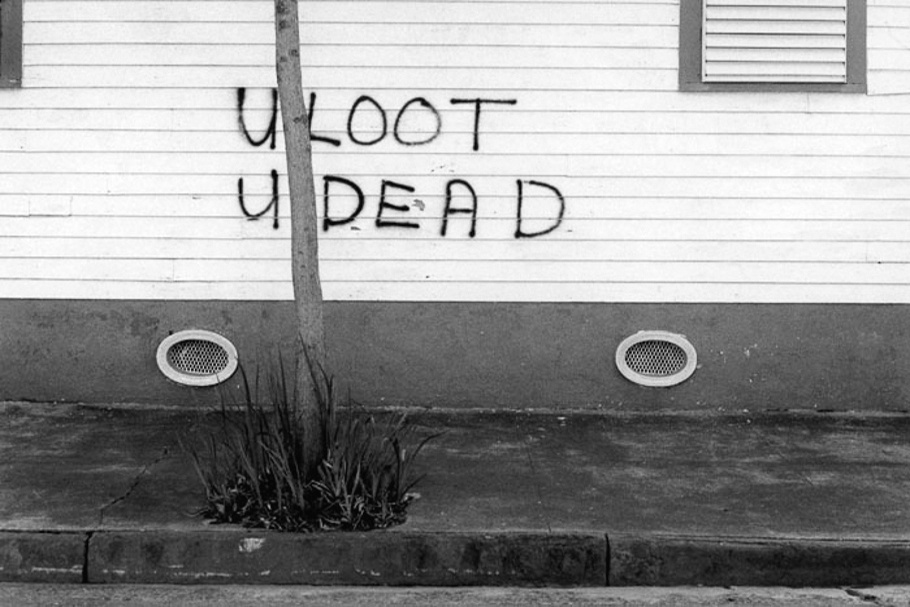

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-010-910

U Loot, U Dead.

New Orleans, LA, 2006

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-011

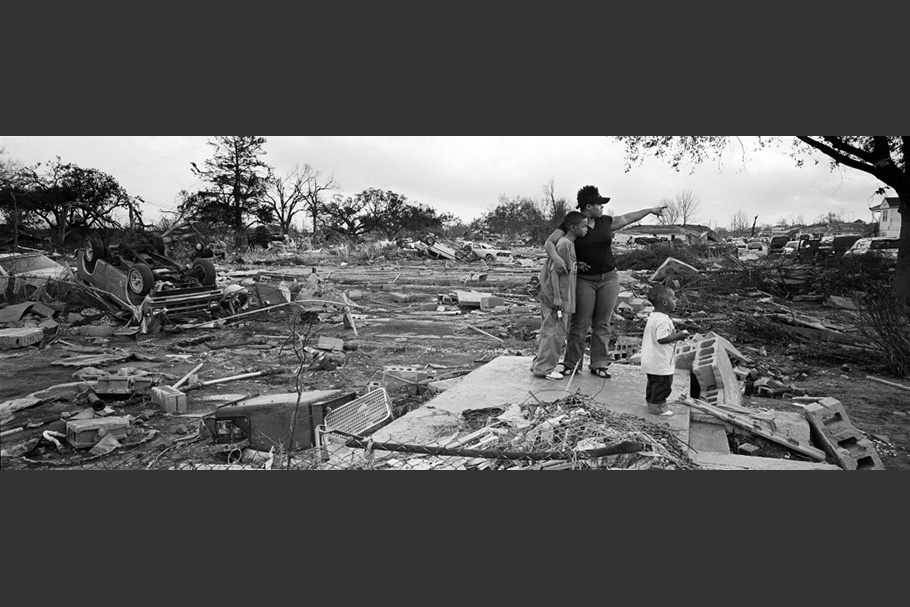

A family returns to the remains of their house for the first time since Katrina.

Lower Ninth Ward, New Orleans, LA, January 2006.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-012

The same place, photographed a year and a half later.

Lower Ninth Ward, New Orleans, LA, July 2007.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-013

Thalita Halley, 14, cries on the steps where her local candy store once stood.

Lower Ninth Ward, New Orleans, LA, July 2007.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-014

“I think I have more chances in Houston; the schools are better. I am going now to the 9th grade. I never see my old friends anymore. Two friends, I don’t even know if they are still alive. I know it’s better for me to stay in Houston, but home is New Orleans. Home is home.”

—Thalita Halley, 14

Halley lost her house after Katrina, and has been living in Houston since then. On her first visit home since the hurricane, she removes the remaining bricks from her destroyed house.

Lower Ninth Ward, New Orleans, LA, July 2007.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-015

I used to live in Midcity in New Orleans. On the Sunday before the storm, we went to a motel. Our home was only a ground floor. But the motel got flooded as well, so we decided to walk to the Superdome through the flooded streets. We stayed there three days before buses picked us up and brought us to Houston. We were dropped off at the Astrodome complex. We stayed there till we got an apartment here at ‘Royal Oaks’ on the 4th of October 2005. I have six children, but I am single. I can’t find work here in Houston. I will go to New Orleans just for two months to work. I want to go back permanently, but I have nowhere to stay. I lost everything. FEMA gave me a check for only 2000 dollars."

Rose Lewis, 46.

Houston, TX, June 2007.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-016

Linda Jeffers (right) is from New Orleans and now lives in Houston. An evacuee community advocate, Jeffers has helped many families in Houston who are having difficulty returning to New Orleans.

Houston, TX, July 2007.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-017

The funeral of Damon Brooks, 16, and Ivan Brooks, 17, two brothers who were shot dead on February 15, 2007.

New Orleans, February 2007.

Damon and Ivan Brooks lived in Treme and attended Joseph S. Clark High School, where they played in the school’s marching band. The brothers were riding in the car of a friend when he stopped to give a young man a ride. When the man got out, he turned and shot both brothers and their friend; only their friend survived.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-018

Burial of Damon and Ivan Brooks.

Holt Cemetery, New Orleans, February 2007.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-019

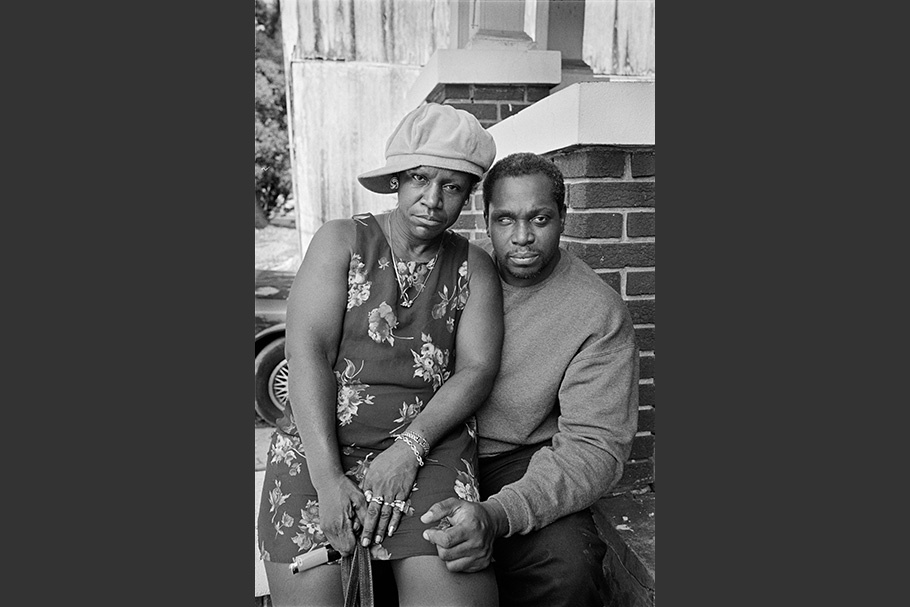

Portrait of Hilda and Michael Hendricks outside their home one year after Katrina destroyed their home. They are still waiting for assistance to help in the rebuilding.

Treme, New Orleans, LA, September 2006.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-020

Hilda Hendricks and her husband Michael try to convince the landlord not to evict the people who are illegally squatting on his property.

Treme, New Orleans, LA, September 2006.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-021

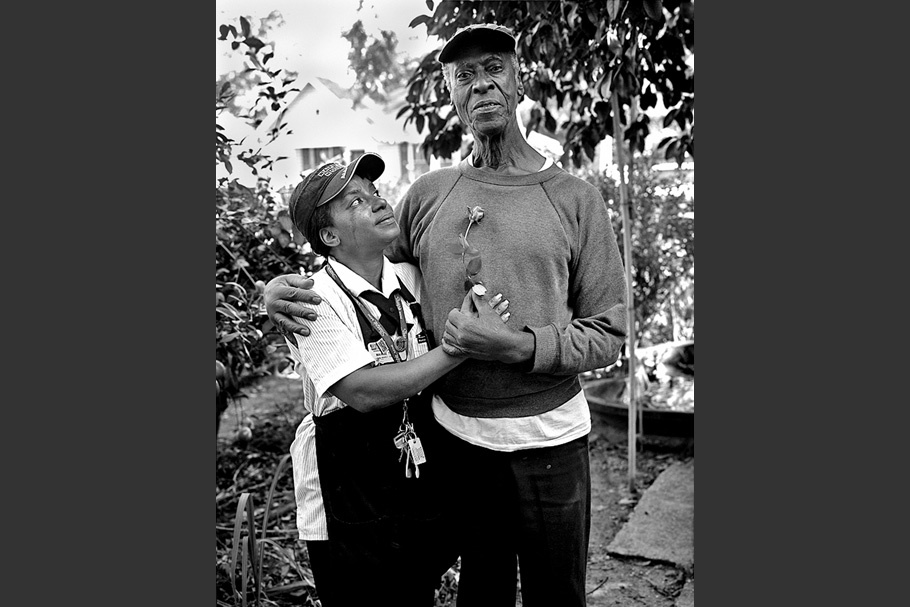

Hilda Hendricks (left) is comforted by her neighbor. Like many people affected by Hurricane Katrina, Hendricks is suffering from severe depression and still worried about her home.

Treme, New Orleans, LA, September 2006.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-022

Michael and Hilda Hendricks walk in their neighborhood, which is still mostly deserted. One year after Katrina, only half of the city’s population had returned.

Treme, New Orleans, LA, September 2006.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-023

Tasha and Muriel Jackson.

Gretna, LA, 2007.

0080313-katrina-mw14-collection-024

William and Margie Tucker.

Mobile, AL, 2006.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-025

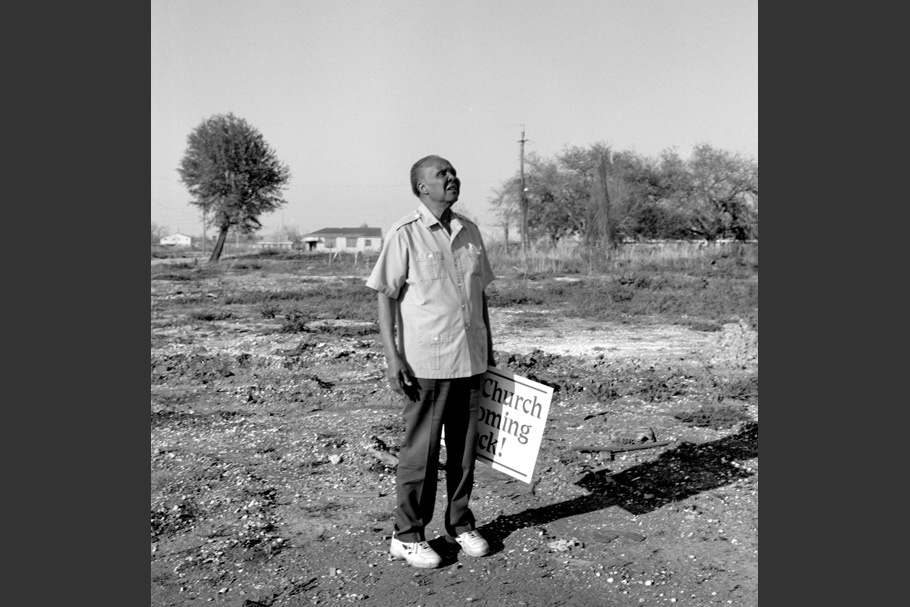

Reverend Adams.

New Orleans, LA, 2007.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-026

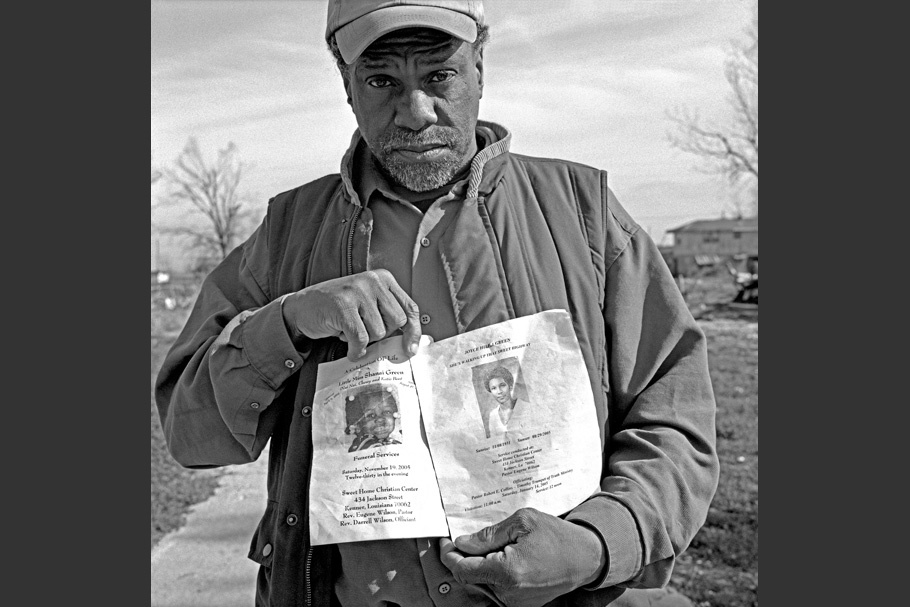

Robert Green with family obituaries.

New Orleans, LA, 2007.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-027

Bridget and Chrishanda, Flood Street.

New Orleans, LA, 2006.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-028

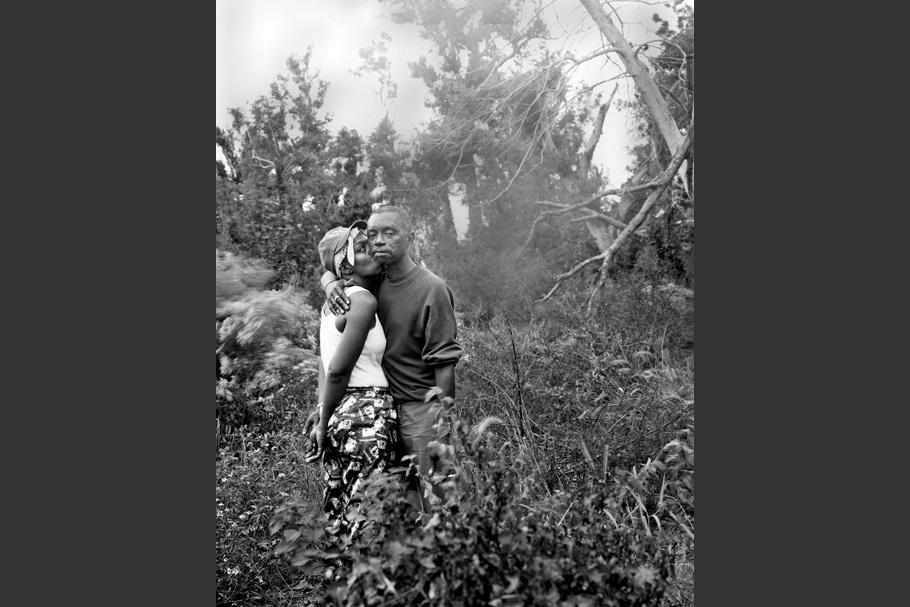

Rodger and Girlfriend.

Biloxi, MS, 2006.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-029

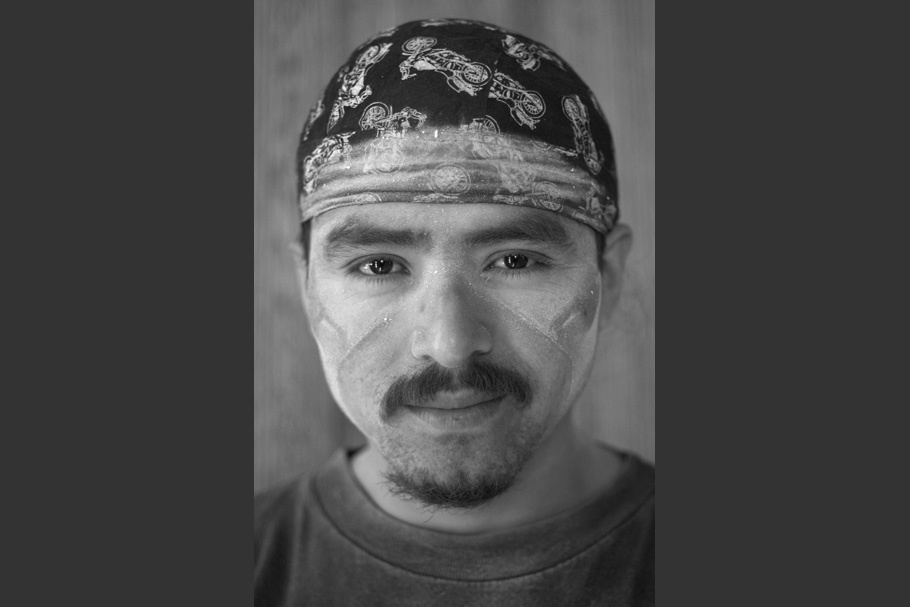

Hispanic worker helps rebuild Keith Calhoun's and Chandra McCormick's photography studio.

Lower Ninth Ward, New Orleans, LA, February 2008.

Since Katrina, New Orleans has experienced a large influx of citizen and noncitizen migrant workers, who have come to the city in search of jobs.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-030

Hispanic worker at the Royal Omni hotel.

New Orleans, LA, September 2006.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-031

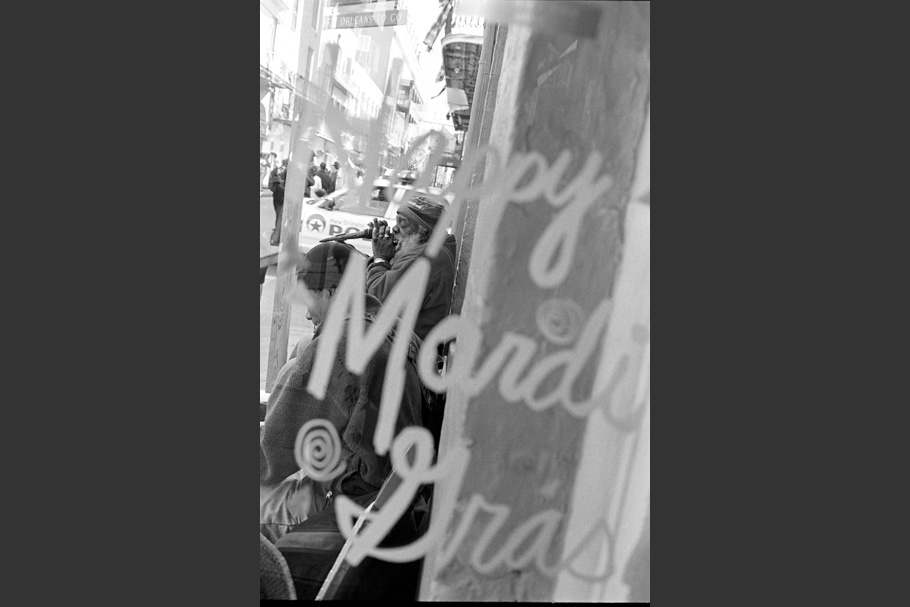

A street performer plays his harmonica during Mardi Gras.

New Orleans, LA, 2007.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-032

The Men of Leisure Social Club make their way through the streets of New Orleans during a funeral dirge.

New Orleans, LA, 2007.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-033

Culture and tradition run deep in New Orleans. A young man plays his horn during a Second Line parade.

New Orleans, LA, 2007.

20080313-katrina-mw14-collection-034

Unable to use the interior of their water-damaged church, members improvise a baptism outside.

New Orleans, LA, 2007.

20080313-katrina-mw14-035-910

Mrs. Hayes. New Orleans, LA, 2007.

Mrs. Hayes, 92, and her daughter live in a rental apartment in Algiers on the West Bank of New Orleans. During the day, Mrs. Hayes goes to a senior citizens program in their neighborhood. On Sunday, August 28, 2005, at 11 am, they evacuated to Houston, when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans. The handicap tag in the car window is for Mrs. Hayes's grandson, who has multiple sclerosis.

20080313-katrina-mw14-036-910

Taking a Break. Steve Richards at Work. New Orleans, LA, 2007.

20080313-katrina-mw14-037-910

Gerard Ingraham. Pointe à la Hache, Plaquemines Parish, LA, 2007.

Hurricane Katrina wreaked havoc on Plaquemines Parish’s fishing industry. Of 1,300 registered shrimpers in Plaquemines Parish, only 50 were working a year after the storm.

20080313-katrina-mw14-038-910

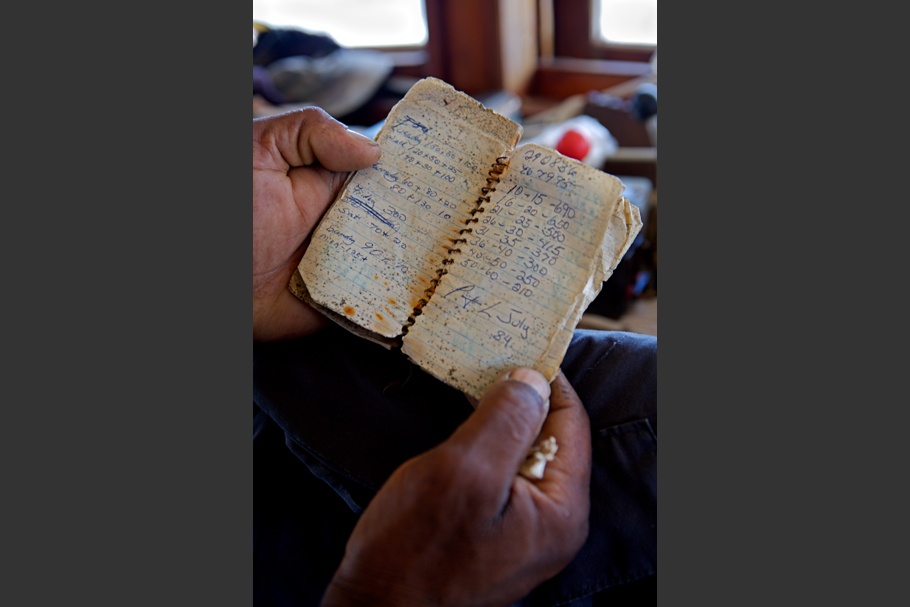

Memories, Doug Wells’ Hands. Pointe à la Hache, Plaquemines Parish, LA, 2007.

A shrimper’s log damaged by the hurricane.

Katrina Media Fellows. The fellowships supported print and radio journalists, photographers, and filmmakers working across a range of disciplines and covering a variety of issues exacerbated or caused by the hurricanes Katrina and Rita.

The fellows include photographers, such as Debbie Fleming Caffery, Keith Calhoun, and Chandra McCormick, who have documented the people and culture of their native Louisiana for over 30 years. For them, the fellowship offered an opportunity to expand an ongoing body of work and reflect on the disaster’s impact on local residents and displaced communities. Other fellows also had a personal connection to the Gulf Coast: Clarence Williams was visiting relatives in New Orleans when Katrina hit, and the experience prompted him to move from Los Angeles to New Orleans in order to continue documenting issues of racism, poverty, and government neglect brought to light by the hurricane. For others, such as Stanley Greene, Joseph Rodriguez, Kadir van Lohuizen, and Michael Williamson, professional assignments or personal projects documenting the immediate aftermath of the hurricanes drew them to the Gulf Coast, as well as to places to which residents were displaced. The fellowships allowed these photographers to engage in long-term, in-depth projects that are an extension of their reporting and social documentary work in other parts of the United States and the world.

Salimah Ali, Gerald Cyrus, Collette V. Fournier, Russell K. Frederick, Wayne Lawrence, John Pinderhughes, Radcliffe Roye, Frank Stewart, and Shawn Walker, are part of a New York–based collective of African-American photographers called Kamoinge. In keeping with the group’s mission, the collective received a fellowship to document the devastation’s far-reaching ramifications on the economic, social, and racial fabric of Gulf Coast residents. Many photographers from the Kamoinge collective had previously photographed the people, architecture, and culture of New Orleans and other parts of the region prior to the hurricanes. The fellowship allowed them to continue this work by traveling to the Gulf Coast’s most publicized areas (such as New Orleans’s Lower Ninth Ward), as well as forgotten coastal towns (such as Pointe à la Hache in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana).

Salimah Ali is a New York–based photographer whose work has appeared in a number of publications, including Essence, Black Enterprise, USA Today, the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and Washington Post; she is a member of Kamoinge, an African American photographers’ collective.

Debbie Fleming Caffery has been making photographs of the people and culture of her native Louisiana for over 30 years.

Born and raised in the Lower Ninth Ward, Keith Calhoun is a New Orleans photographer committed to documenting the local culture, spirit, and people of his hometown.

Gerald Cyrus was born in 1957 in Los Angeles, California, where he began photographing in 1984. He is a member of Kamoinge, an African American photographers’ collective.

Collette V. Fournier is an award-winning New York–based photographer whose work has been published and exhibited widely and is included in a number of museum collections, such as the Smithsonian Institution and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; she is a member of Kamoinge, an African American photographers’ collective.

Russell K. Frederick is a Brooklyn–based photographer whose work has been exhibited widely and who has collaborated with some of the industry’s best. He is a member of Kamoinge, an African American photographers’ collective.

Stanley Greene has been photographing major worldwide news events since 1989.

Wayne Lawrence is a Brooklyn-based photographer who specializes in documentary portraiture; he is a member of Kamoinge, an African American photographers' collective.

Kadir van Lohuizen is an internationally recognized professional freelance photojournalist who has covered stories about Africa, Asia, the former Soviet Union, and the Middle East in numerous magazines and newspapers, and has worked regularly for Medecins sans Frontieres since 1990.

Chandra McCormick is a documentary photographer who is renowned for capturing many different aspects of New Orleans culture, as well as the lifestyles of her fellow New Orleanians.

John Pinderhughes is a New York–based commercial and fine art photographer with over 30 years of experience; he is a member of Kamoinge, an African American photographers’ collective.

Joseph Rodriguez is a New York–based freelance photojournalist whose work has appeared in publications such as the New York Times Magazine, National Geographic, Marie Claire, GQ, Jane, Ebony, Mother Jones, Newsweek, American Photo, B&W, and Stern.

Radcliffe Roye is a Brooklyn, New York–based documentary photographer specializing in environmental portraits, photojournalism, and stock photography; he is a member Kamoinge, an African American photographers’ collective.

Frank Stewart is an award-winning, New York–based photographer whose work has been included in solo and group exhibitions at venues such as the Studio Museum in Harlem, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, International Center of Photography, Museum of Contemporary Art (Los Angeles), and the Corcoran Gallery; he is a member of Kamoinge, an African American photographers’ collective.

Shawn Walker is a New York–based photographer whose work is exhibited and collected by major institutions, including the Brooklyn Museum, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Whitney Museum of American Art, International Center of Photography, Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco Museum of Art, and the Studio Museum in Harlem; he is a member of Kamoinge, an African American photographers’ collective.

Pulitzer Prize–winning photojournalist Clarence Williams lives in New Orleans, where he documents ongoing racism, poverty, and government neglect in Katrina’s wake.

Michael Williamson is a staff photographer at the Washington Post.

Photographs by the Open Society Foundations’ Katrina Media Fellows

The aftermath of the 2005 hurricanes Katrina and Rita underscored persistent problems of poverty, racism, and government neglect plaguing the United States. Yet, mere months after the destruction of New Orleans, Louisiana, and other parts of the Gulf Coast, the public’s attention had, for the most part, shifted elsewhere. In early 2006, the Open Society Foundations created a fellowship competition to support in-depth media projects as a means of stimulating and sustaining a national conversation concerning the critical issues laid bare by the hurricanes.

Katrina Media Fellowships supported more than 50 fellows working on 31 print, radio, photography, and film projects. Some fellows pursued individual projects, while others worked collaboratively. Many projects focused on historically neglected groups—African Americans, Native Americans, first and second generation immigrants, incarcerated people, low-income and rural communities. The projects exposed problems caused or illuminated by the storms—government inefficiency and neglect, misuse of public funds, the role of private contractors, and ineffective clean-up and rebuilding efforts. By exploring these issues, the fellows worked to expand and deepen the public’s understanding of race and class inequity in the United States, and inform the handling of future natural and man-made disasters.

The images presented here are only a small selection of the photography fellows’ work. Some images, such as those by Frank Stewart and Michael Williamson, document the surreal nature of the altered physical landscape in the days and months immediately following the storms. Photographs by Stanley Greene and Gerald Cyrus of still-damaged schools and neighborhoods taken a year or two after the storms attest to the shockingly slow pace of rebuilding and the urgent need to keep national attention focused on the Gulf Coast. As Shawn Walker’s photograph shows, by placing graffiti, handmade signs, and impromptu memorials on buildings and in the streets, residents have used the public sphere to express their frustration with the government’s response

The personal toll of government neglect, displacement, and increased urban violence is documented in photographs, by Joseph Rodriguez and Kadir van Lohuizen, in which residents confront an overwhelming number of obstacles in their attempt to return to and rebuild their communities. Photographs by Salimah Ali, Debbie Fleming Caffery, Keith Calhoun, Collette Fournier, Russell K. Frederick, Wayne Lawrence, Chandra McCormick, John Pinderhughes, and Radcliffe Roye offer profiles of residents living and working in the post-Katrina and Rita landscape. These images place residents within the context of their hurricane-damaged environments, whether in Biloxi, Mississippi, Mobile, Alabama, or New Orleans and Pointe à la Hache, Louisiana. Yet rather than depict residents as singularly defined or overwhelmed by their experiences, these photographers capture the dignity and determination of residents as they attempt to reclaim their homes and lives.

As problems with housing, employment, health care, and public education threaten residents’ ability to maintain their communities, culture and religion gain a heightened sense of importance, as both provide opportunities for community building and healing. Photographs by Clarence Williams, for example, convey the persistence of cultural traditions and religious practices, even in the face of disaster.

As a whole, the photographs taken by the Katrina Media Fellows shed light on the devastation’s ongoing legacy and its impact on the daily lives of Gulf Coast residents. Moreover, the issues the photographs raise attest to the ongoing need for continued media coverage documenting the injustices faced by residents of the Gulf Coast.

—February 2008