20070612-herster-mw13-collection-001

Lawyers representing Guantánamo detainees photographed with the detainees’ families.

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-002

Detainee: Abdulaziz Al Swidi

Home country: Yemen

Represented by: Allen & Overy

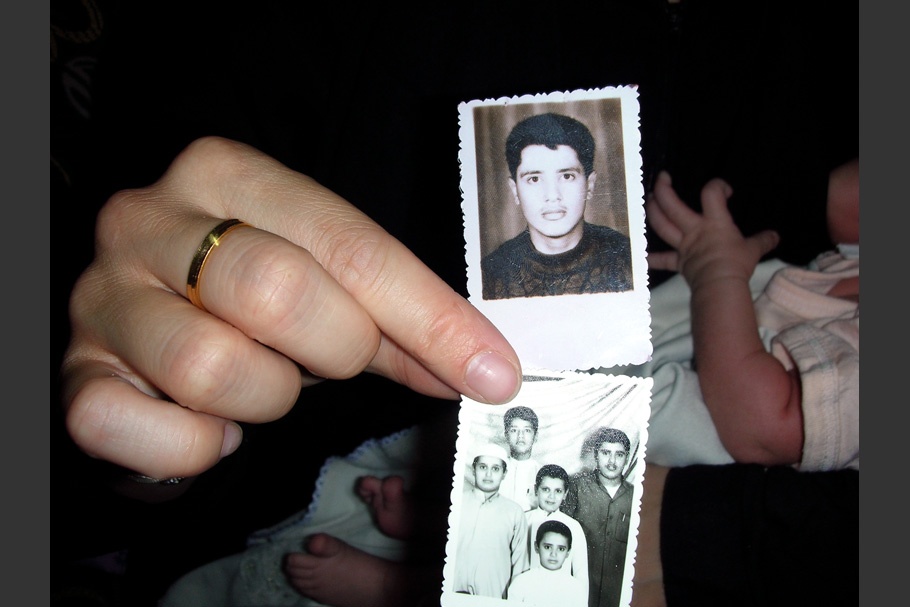

Attorney Sarah Havens holding pictures of Abdulaziz and his sister’s newborn daughter.

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-003

Detainee: Abdulkhaleq Al Baidhani

Home country: Yemen

Represented by: Allen & Overy

Lunch served to attorneys by Abdulkhaleq’s family.

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-004

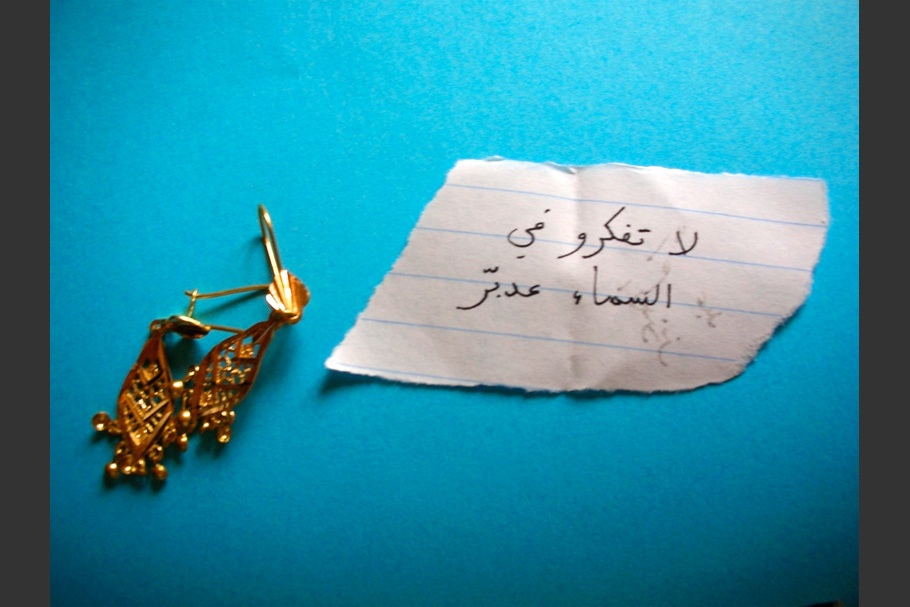

Detainee: Abdulaziz Al Swidi

Home country: Yemen

Represented by: Allen & Overy

Gift that attorney Sarah Havens purchased for Abdulaziz’s mother at his request.

Note reads: “Don’t despair, someone in the sky is taking care.”

“Abdulaziz said he wanted jewelry for his mother and his wife, something they could wear all the time and remember him. He said, ‘I have three daughters, a wife and a mother. I love them all very much and I want to give them presents but I can’t. I obviously have no money; I don’t have any access to anything. Would it be possible for you to go and bring gifts to them from me?’ So he became very thoughtful and thought of something specific he wanted for each of his daughters, his wife, and his mother and gave specific instructions for us. Of course, he was thrilled when we came back and told him that we gave them the gifts he requested.”

—Notes from interviews with Sarah Havens & Doug Cox, lawyers for detainee Abdulaziz Al Swidi

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-005

Detainee: Abdulkhaleq Al Baidhani

Home country: Yemen

Represented by: Allen & Overy

Abdulkhaleq’s nephew.

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-006

Detainee: Abdulkhaleq Al Baidhani

Home country: Yemen

Represented by: Allen & Overy

Abdulkhaleq’s family’s livestock.

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-007

Detainee: Abdulkhaleq Al Baidhani

Home country: Yemen

Represented by: Allen & Overy

Abdulkhaleq’s family’s store.

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-008

Detainee: Riyad Al Haj

Home country: Yemen

Represented by: Allen & Overy

Riyad’s father.

“Riyad is such a fragile character and seems so alone and does not have much family that can support him. The fact that it was going to be difficult to find Riyad’s dad, that it was something really important and meaningful to Riyad was weighing heavily on us in Yemen.

“The last day we were in the hotel lobby in Sana’a. The only picture I had ever seen of Riyad’s dad was a bad photocopy of his ID card. I saw this little old man walking through the lobby and it looked a little bit like him. He was walking toward the exit and talking to some of the guards, saying ‘Americayeen (Arabic for Americans).’ I said, ‘You’re Riyad’s dad.’ He said, ‘Oh yes, yes.’ This poor man was so out of place in this hotel lobby. It was the nicest hotel in Sana’a with marble everywhere and giant flower arrangements with this little old man, from a very modest background, basically blind and confused in the lobby. He then started asking us what happened with Riyad. He had heard that Riyad’s legs had been cut off, that they had put things in Riyad’s ears—like electric shock so that he couldn’t hear and that he was blind. The minute he sat down with us he started crying. We said, ‘We saw Riyad literally eight days ago; he’s fine.’”

—Notes from interviews with Sarah Havens & Doug Cox, lawyers for detainee Riyad Al Haj

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-009

Detainee: Adel Al Nussairi

Home country: Saudi Arabia

Represented by: Weil Gotshal & Manges

Attorney Anant Raut (right) with Adel’s cousin (middle) and friend at a hotel in Bahrain.

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-010

Detainee: Fahmi al Tawlaqi

Home country: Yemen

Represented by: Allen & Overy

Fahmi’s living room.

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-011

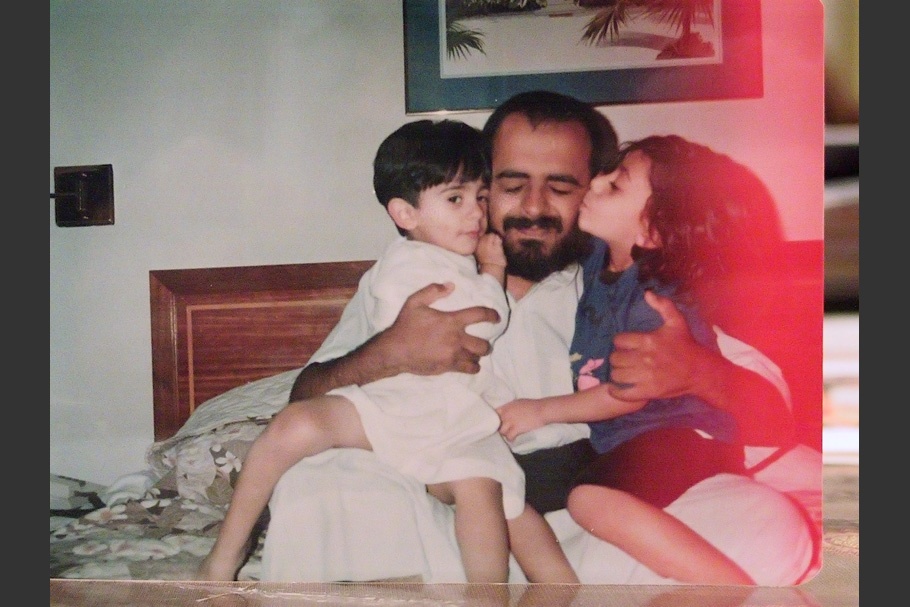

Detainee: Fuad Al-Rubiah

Home country: Kuwait

Represented by: Shearman & Sterling

Re-photographed snapshot of Fuad and his children before he was detained.

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-012

Detainee: Omar Rajab Amin

Home country: Kuwait

Represented by: Shearman & Sterling

Omar’s mother and sons.

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-013

Detainee: Ali Yahya Mahdi

Home country: Yemen

Represented by: Allen & Overy

Ali’s nephew and father.

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-014

Detainee: Jumah Al Dossari

Home country: Bahrain

Represented by: Dorsey & Whitney

Attorney Josh Colangelo-Bryan with Jumah’s father and brother at the Bahrain Bar Association.

“During the first meeting with Jumah, not only did he say ‘see you later alligator,’ but later he looked at me in a sardonic way and said, ‘don’t worry, be happy.’ During the same meeting, he also would pull away from the table and put his hands to his face and in a stream of consciousness-like way describe abuses he suffered in U.S. custody. At the end of our meeting, he said, ‘What do I do to keep myself from going crazy?’

“In October 2005, I was back for another visit. After about an hour or so he said he had to go to the bathroom. After a few minutes, I hadn’t heard anything from inside, so I let it go a couple of minutes. I started to feel really anxious. I opened the door. The first thing I saw was a big puddle of blood. I looked up and saw Jumah hanging from his neck from the top of the steel mesh wall. I was literally two inches from his face, but I couldn’t get to him because of the wall. His head was pulled back, his eyes rolled back in his head, his lips and mouth swollen. I saw that he had a big gash in his arm.

“I called the military police and after fumbling with the keys, they cut the noose. He wasn’t breathing. I yelled to do CPR and bind his arms, and the sergeant said I had to get out of the room. I didn’t want to have an argument. As I walked out, I heard Jumah gasp for air, which I took as a good sign.

“Obviously I had to tell Jumah’s family about what I had seen. The hardest part was that after being told by the military that Jumah had surgery, the government refused to provide any more information. All I could tell the family was that I had seen Jumah try to kill himself, that I’ve been told he had surgery and was recovering physically, but beyond that I had no new information.”

—Notes from interview with Josh Colangelo-Bryan, lawyer for detainee Jumah Al Dossari

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-015

Detainee: Abdulaziz Al Swidi

Home country: Yemen

Represented by: Allen & Overy

Abdulaziz’s younger brother.

“Abdulaziz’s older brother passed away suddenly not long ago, and the family doesn’t want us to reveal it to him. They want to be able to tell him when he returns under the right circumstances.

“We visited Abdulaziz’s family twice. The first night, it was the younger brothers all running around, and we took all of their pictures. When we returned, the oldest brother was there and we asked if we could take his picture. He said, ‘I prefer that you didn’t because if there was a picture of me, Abdulaziz would see pictures of all the brothers except for the one brother who died. It’s best if some of us are not included.’”

—Notes from interviews with Sarah Havens & Doug Cox, lawyers for detainee Abdulaziz Al Swidi

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-016

Detainee: Abdullah Al Anazi

Home country: Saudi Arabia

Represented by: Weil Gotshal & Manges

Abdullah’s bedroom.

“Abdullah is a guy who has lost both of his legs since he was captured. His legs were injured during the U.S. bombing of Afghanistan. And still he has managed to make peace with himself and his surroundings.

“Abdullah’s mother has turned his room into a shrine for him. They have his favorite clothes set out, hanging on the closet. They’ve pretty much left the room as he remembers it so it is waiting there ready for him when he comes back.”

—Notes from interview with Anant Raut, lawyer for detainee Abdullah Al Anazi

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-017

Detainee: Abdullah Al Anazi

Home country: Saudi Arabia

Represented by: Weil Gotshal & Manges

Abdullah’s nieces and nephews holding his Guantánamo mug shot.

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-018

Detainee: Abdullah Al Anazi

Home country: Saudi Arabia

Represented by: Weil Gotshal & Manges

Abdullah’s favorite landscapes and drawings by his nieces and nephews.

20070612-herster-mw13-collection-019

Detainee: Ali Al Rezehi

Home country: Yemen

Represented by: Allen & Overy

The men and children of Ali’s family.

Margot Herster is an artist and freelance photographer based in New York City and Austin, Texas. Herster holds an MFA in Photography, Video, and Related Media from the School of Visual Arts in New York City, as well as undergraduate degrees in psychology and art history from the University of Kansas.

Herster’s work focuses on the social and psychological dynamics of family and interpersonal relationships. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, including as a solo exhibition at SCALO Project Space in New York.

In response to the lack of information available about the individuals detained at Guantánamo, she developed the exhibition Guantánamo: Pictures from Home and the accompanying website: www.throughthewalls.org. The project, which combines photographic, audio, and video components, debuted as a large-scale exhibition at FotoFest in Houston in March 2007.

Margot Herster

Legal scholars have called Guantánamo the most important civil liberties case in half a century. Since 2002, the United States has detained over 700 men, holding them virtually incommunicado after their post-9/11 capture. The administration labeled the detainees “the worst of the worst,” but officials and outside analysts have questioned the accusations against them. Government documents reveal that only 8 percent of detainees are characterized as Al Qaeda fighters, and less than half are suspected of committing hostile acts against the United States or its allies. While courts, attorneys, politicians, and human rights groups deliberate over living conditions, interrogation tactics, and the prison’s fundamental legality, those directly affected by these policies remain hidden.

The U.S strategy to obscure transparency of Guantánamo includes restrictions on photography. The only images are of faceless orange jumpsuits and shackled hands taken by military photographers and censored journalists.

My connection to this issue compelled me to develop Guantánamo: Pictures from Home. My husband is an attorney with Allen & Overy, a law firm that represents 11 Yemini nationals at Guantánamo. The more I learned about the individual detainees, the more I wanted to know: Who are they? What do they look like?

In June 2005, my husband’s colleagues traveled to Yemen to meet their clients’ families. When they returned, I asked to see their photographs. Their images hinted at the detainees’ personal and cultural lives, and revealed the burden carried by the families. Subsequently, I collected the photographs that attorneys from five major law firms, which represent 45 detainees from Afghanistan, Bahrain, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen, had taken on trips to their clients’ home countries. These images, originally intended to provide evidence that the families trusted the American lawyers to represent their sons, have become treasured objects within Guantánamo. For many detainees, the photographs are the only link to their families back home.

Amateur digital photographers have produced some of the most incisive recent wartime photographs. Abu Ghraib revealed the dehumanization engendered by war and the abuse of power, and snapshots of U.S.-bound, flag-covered caskets fixed the cost of war in American life. Guantánamo: Pictures from Home highlights the power of photography to build trust and sustain family relations, and to provide the public with an intimate look into the lives of the people detained at Guantánamo.

—Margot Herster, June 2007