20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-001

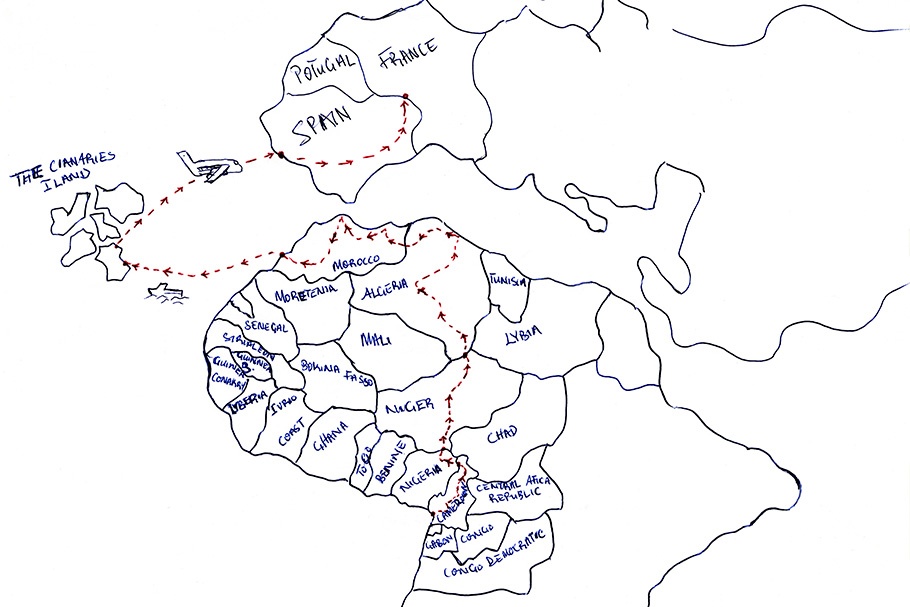

A map drawn by Kingsley showing the route of his journey.

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-002

Kingsley tells his parents that he is leaving for France. They have given him money for the trip.

Limbe, Cameroon, May 2004

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-003

Kingsley sits on the bus that will take him to the northern part of the country.

Yaounde, Cameroon, May 2004

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-004

The Agadez depot, considered the gateway to the Sahara desert.

Agadez, Niger, May 2004

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-005

Migrants crammed into the back of the four-wheel drive vehicle that will take them across the Sahara desert.

Sahara desert, between Niger and Algeria, June 2004

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-006

Crossing the Sahara desert.

Between Niger and Algeria, June 2004

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-007

The least bit of shade is a welcome relief from the heat, which can exceed 120 degrees Fahrenheit during the day.

Sahara desert, between Niger and Algeria, June 2004

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-008

Following a ten-day wait, more than thirty migrants are crammed into the back of a four-wheel drive vehicle that will take eight days to cross the desert.

Sahara desert, between Niger and Algeria, June 2004

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-009

Kingsley and several of his compatriots scope out the Spanish enclave of Melilla from the top of a garbage heap at the edge of town. The smugglers demand large sums of money to get the immigrants past the barbed wire fence.

Nador, Morocco, July 2004

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-010

The boat furnished by the smugglers capsizes less than 1000 feet off the Moroccan coast on this first attempt to cross the ocean to the Canary Islands. Many aboard cannot swim and two men drown.

Western Sahara, Morocco, September 2004

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-011

Kingsley has repaired the boat but is still apprehensive about boarding.

Western Sahara, Morocco, September 2004

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-012

Kingsley and his group take off a second time, ten days after the boat capsized. They are under constant surveillance by the smugglers, who are armed with knives. Once they are close to the Canary Islands, they will be recovered by the Spanish Coast Guard and taken to a detention center.

Atlantic Ocean, between Morocco and the Canary Islands, Spain, October 2004

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-013

Kingsley and his group take off a second time, ten days after the boat capsized. They are under constant surveillance by the smugglers, who are armed with knives. Once they are close to the Canary Islands, they will be recovered by the Spanish Coast Guard and taken to a detention center.

Atlantic Ocean, between Morocco and the Canary Islands, Spain, October 2004

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-014

After three weeks at a dentention center in the Canary Islands, Kingsley is released because the Spanish authorities cannot determine his nationality. He and his fellow migrants are flown to mainland Spain.

Malaga, Spain, November 2004

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-015

Kingsley and his fellow migrants.

Malaga, Spain, November 2004

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-016

Kingsley’s new life begins. His immigration status has been regularized, and he has found employment at a warehouse. He spends a total of three hours commuting to and from the job.

Cergy-Pontoise, France, December 2005

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-017

Kingsley waits at a bus shelter. The long commute and extended work day leave little time for much else.

Cergy-Pontoise, France, December 2005

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-018

Kingsley works ten-hour days at his warehouse job.

Cergy-Pontoise, France, December 2005

20070612-jobard-mw13-collection-019

The migrants lost all of their belongings—even their shoes—when the boat capsized.

Western Sahara, Morocco, September 2004

Born in 1970, Olivier Jobard entered the École Louis Lumière in 1990. After completing an internship at Sipa Press, he joined Sipa as a staff photographer in 1992.

His work has taken him around the world and into the heart of conflict zones in Afghanistan, Bosnia, Chechnya, Colombia, Croatia, Iraq, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Sudan.

In 2004, he documented the passage of one immigrant from Cameroon to France over the course of six months. This human adventure resulted in a book published by Marval Publishers in France.

Olivier Jobard

The United Kingdom is the most popular destination for immigrants in Europe. Some travel there because of family connections or cultural ties; others put themselves in the hands of smugglers, abandoning any control over their final destination.

In 2000, I visited the now-closed Red Cross shelter in Sangatte, France, just down the road from the entrance to the Channel Tunnel. The shelter was established to aid the large numbers of migrants who gathered there, waiting for their chance to cross the channel through the tunnel or on ferries.

Many of the migrants were fleeing conflicts in Africa and elsewhere that I had covered as a photojournalist. For two years I returned periodically to Sangatte, listening to people recount their journeys from distant lands, and express their hopes for a better life in Europe.

After listening to their stories, I felt compelled to document their passage—to put faces to those usually called “sans-papiers,” people without papers. I decided to accompany one migrant on his six-month trek across half of Africa.

Kingsley is a 23-year-old lifeguard from the West African coastal town of Limbe, Cameroon. Kingsley worked at an upscale hotel giving swimming lessons to European tourists. He earned 50 euros a month, just enough to pay for food and rent for the two-room house he shared with his parents and seven siblings.

In Limbe, almost every person talked about crossing the desert to get to Europe. Kingsley believed in the European dream. In 2004, he left Cameroon on an excruciating six-month journey. He crossed Nigeria, Niger, the Sahara Desert, and Algeria. The driver of the truck had to stop often because of engine problems. Other migrants joined the caravan or left. The more they drove, the more they suffered from the heat, sun, and dust. Finally, he reached Morocco. He waited there for three months before boarding a makeshift skiff bound for the Canary Islands. For Kingsley, crossing the desert and the ocean was the only way to make it out. And six months after leaving Cameroon, he finally set foot on European soil.

I hope that Kingsley’s journey shows the willingness of people to abandon everything—family, culture, and past—for the dream of finding a better life abroad.

—Olivier Jobard, June 2007