20070612-burtynsky-mw13-collection-001

Urban Renewal #6, Apartment Complex

Jiangjun ao, Hong Kong, 2004

Urban Renewal

Under Mao Zedong’s government, starting in 1949 and continuing for nearly three decades, population growth was encouraged as it was considered an asset to long-term development. The population of China in 1950 was 550 million. Today it stands at 1.3 billion. In 1952, urban dwellers numbered 72 million. By 2003 that number rose to almost 524 million people. Recent estimates indicate that because of economic development and the resulting annexation of outlying rural areas, China’s urban populace will, over the next 40 years, increase dramatically to over one billion city dwellers—the equivalent of the combined population of today’s North and South American continents as well as the entire European Union.

During the 1960s and 1970s, China imposed very strict limits on migration as a way to maintain reasonable living standards in the cities. Today however, China is experiencing the largest country-to-city migration in history. Millions are leaving their farms for urban centers. Huge cities like Beijing and Shanghai attract peasants from the countryside who search for opportunities to participate in the new economy. Accommodation for these new city-folk will require a feat of urban planning and governance on a scale the world has never seen. It is estimated that from 80 to 120 million migrant laborers are working, or looking for work, in China’s booming cities.

In recent years, Beijing has started building schools to educate the children of migrant workers. Until the 1980s, most Shanghainese lived in houses rarely higher than two stories. Often more than one family lived in one house and a single family might have as many as four generations living together. Today, Shanghai is shaping itself into a modern international city. Between 1990 and 2002, as much as 38 million square meters of older houses and apartments were removed to make room for modern residential and commercial properties.

The government owns all land in China, but people have the right to use or occupy the land. Shanghai City’s plan to modernize has developers from around the world eager to profit. Many of central Shanghai’s old houses sit on the most desirable parcels of land. Often citizens will be notified of their residential termination by the sudden appearance of the now-ubiquitous Chinese character chai, or demolish, painted on the outside of their building. Under Chinese law, the government will provide substitute housing for residents of redevelopment areas, even if these substitutions are located hours away in the suburbs. To some, the idea of moving into a new apartment that has functional interior plumbing with hot water, something often lacking in older houses, is a welcome change. But to many, the dismantling of their community and the lack of satisfactory compensation for prime real estate signifies a battle worth fighting.

20070612-burtynsky-mw13-collection-002

Three Gorges Dam Project, Wan Zhou #2

Yangtze River, China, 2002

Three Gorges Dam

The Three Gorges Dam is the world’s largest and most powerful hydroelectric dam. Located on the Yangtze River, and straddling Hubei and Sichuan provinces, the dam stretches 1.2 miles across (five times wider than America’s Hoover Dam) and stands 607 feet high. Its completion will result in the creation of an adjacent 373-mile lake. Construction, which began in 1993, is slated for completion by 2009. The dam’s primary functions will be to generate electricity, control floods and provide for inland shipping. In full operation, this dam will generate 18,200 megawatts of electricity from 26 turbines (the output of approximately 16 nuclear power plants). Budgeted investment is nearly $25 billion, but some dam watchers say costs could rise to as much as $75 billion by completion.

Plans to dam the Yangtze have existed for nearly a hundred years. Sun Yat-sen, the “Father of the Revolution,” is often identified as being one of, if not the, first proponent of the dam. However, the original plans were shelved due to unfavorable political and economic conditions until April 3, 1992, when the Seventh National People’s Congress (NPC) finally approved it. Former Premier Li Peng, who had long ties to the power industry in China, was a major champion of the project.

Building mega dams in the 21st century has gathered much global criticism and is central to a growing debate. To make room for the Three Gorges Dam, approximately 1.13 million people must be relocated and their livelihoods challenged; it is the largest peacetime evacuation in history. Fertile agricultural lands and important cultural and historic sites will be found submerged under a vast reservoir. By 2009, 13 major cities, 140 towns and over 1,300 villages—along with 1,600 factories and mines and an unknown number of farms—will have vanished beneath its surface.

The winners of this massive undertaking include those who improved their standard of living and benefited from new housing and new opportunities. China’s industries, hungry for electricity, also win. However, there are many who must face short-term hardship. For instance, farming families stand to lose much as their ancestral lands disappear, often without sufficient compensation. Farmers relocated to land parcels further uphill face the prospect of poor soil, steep slopes and erosion. Furthermore, schemes aimed at integrating farmers into urban economies have met with very limited success. Environmental degradation, escalating costs and human rights concerns are the main issues entangling mega-dam projects today. Experts argue that a series of smaller dams may enable more effective strategies for dealing with flood control. However, the Three Gorges Dam project is a source of intense national pride and the government’s masthead project to show the world its capability to realize formidable accomplishments.

20070612-burtynsky-mw13-collection-003

Three Gorges Dam Project, Wan Zhou #1

Yangtze River, China, 2002

20070612-burtynsky-mw13-collection-004

Three Gorges Dam Project, Feng Jie #6

Yangtze River, China, 2002

20070612-burtynsky-mw13-collection-005

Three Gorges Dam Project, Dam #4

Yangtze River, China, 2002

20070612-burtynsky-mw13-collection-006

China Recycling #9, Circuit Boards

Guiyu, Guangdong Province, China, 2004

E-Waste

Since the birth of the digital age, industrialized nations have continuously replaced older electronic communications infrastructures with modern ones, resulting in a great deal of electronic waste, or e-waste. In order to divert these obsolete toxic materials from our own landfills in the West, “recyclers” came forward offering to take them away. For this service there is a collection fee. These agents then sell to Chinese scrap buyers, thereby making money on both ends of the transaction. Everything from massive switching stations and industrial computers to hospital technology and old schoolroom computers—in short, all obsolete electronics, even old rotary phones—are today packed into containers, then shipped to China and other developing nations. It is estimated by the recycling industry that 80% of the e-waste collected in North America for recycling goes offshore and out of that amount 90% goes to China.

E-waste is hazardous and its processing is a high-risk endeavor even in state-of-the-art facilities. In China, e-waste recycling is, for the most part, not yet a refined industry. Once the scrap arrives at its destination, workers use their hands and primitive tools to pick apart the junked computers and salvage precious components. In the process, they expose themselves and their environment to toxic elements such as lead, mercury and cadmium.

In China many of the people involved in this process are farmers who stopped tilling their land in favor of the more lucrative e-waste recycling trade. The farmers earn about $1.50 per day cooking circuit boards to remove components, sloshing corrosive acid solutions over removed chips and burning wires and other plastic-coated parts to liberate metals. These are routine operations conducted by workers of all ages and both genders with a minimum of occupational health protection or appropriate equipment.

Environmental groups like the Basel Action Network, who first reported on massive imported e-waste operations in China, call this “dumping by another name.” They claim that electronics manufacturers and consumers are in effect “externalizing” real end-of-life liabilities and costs instead of paying for them upfront. This creates a greater profit margin for manufacturers and a subsidy for electronics consumers at the expense of Chinese laborers and their increasingly contaminated communities. Being allowed to pass on this liability to others in far away countries provides little incentive for manufacturers and consumers to take on the added cost and/or initiative for supporting “greening product design” of products that are environmentally responsible.

In 1989, the Basel Convention was adopted to control the international trade of hazardous waste. In 1995, it included an amendment that banned the export of hazardous waste from richer nations to developing nations for any reason, including recycling. It was recognized that trade barriers were needed to protect the poor from receiving a disproportionate burden of the world’s toxic waste, a situation that is considered one of the perverse effects of globalization. The European Union has already implemented this global waste dumping ban, even though it still lacks all of the necessary ratifications for it to become legally binding. Under current Chinese law, the importation of hazardous electronic waste is illegal.

20070612-burtynsky-mw13-collection-007

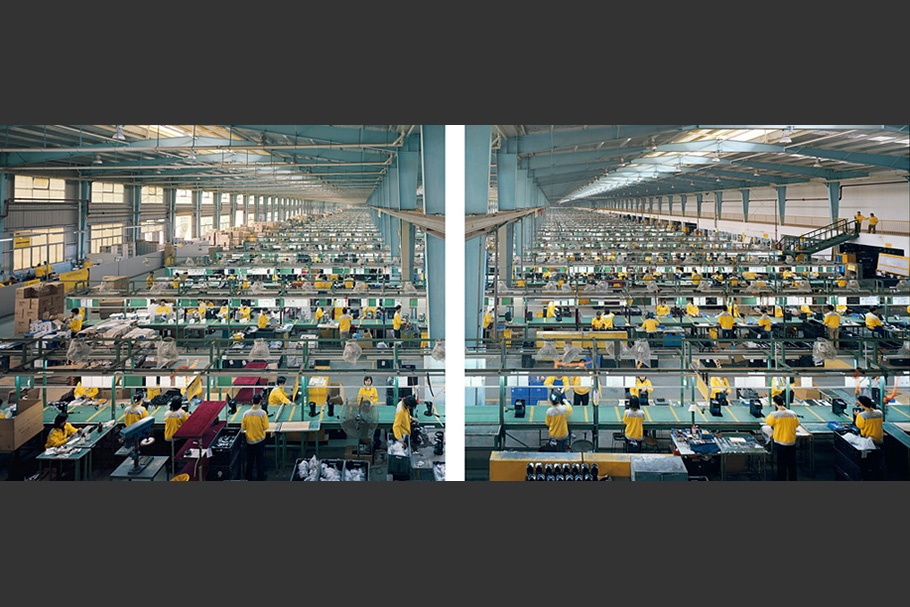

Manufacturing #10A & 10B, Cankun Factory

Xiamen City, China, 2005

Manufacturing

In the southern province of Guangdong, one can drive for hours along numerous highways that reveal a virtually unbroken landscape of factories and workers’ dormitories. These new “manufacturing landscapes” in the southern and eastern parts of China are producing more and more of the world’s goods and have become the habitat for a diverse group of companies and millions of busy workers.

Pick up almost any commonly used product and you won’t be surprised to find that it was made in China. It is here that 90% of Christmas decorations, 29% of color television sets, 75% of the world’s toys, 70% of all cigarette lighters and probably every T-shirt in your closet are made. The hard drive for your iPod mini was made in the city of Guiyang. Located in China’s poorest province, Guiyang is noted more for its poverty than for making state-of-the-art one-inch hard drives. Working the assembly lines, China’s youthful peasant population is quickly abandoning traditional extended-family village life, leaving behind the monotony of agricultural work and subsistence income for a chance at independence.

Inexpensive labor from the countryside, important as it is to China’s growth as a trading nation, is only one major facet of China’s success. Just as important is a rising industrial production capability. China now plays a central role in the global supply chain for the world’s multinational corporations. Wal-Mart alone outsourced $15 billion in manufacturing, making the company (if it were a country) China’s eighth largest trading partner. Altogether, nearly half of foreign trade is tied to foreign-invested enterprises in China. This investment stimulated managerial, organizational and technical expertise that China has fully integrated into its business model. Since the early 1990s, more than one-half trillion U.S. dollars have flowed into this country’s manufacturing sector, mainly from its Asian neighbors—Hong Kong, Korea, Japan, Singapore, Taiwan—and then additionally from North America and Europe. China has moved up the manufacturing ladder, and today, exports an increasingly sophisticated array of products. Its manufacturing future rests not just in being able to absorb technology, but also in becoming an innovator and a source for new technology.

20070612-burtynsky-mw13-collection-008

Manufacturing #18, Cankun Factory

Zhangzhou, Fujian Province, China, 2005

20070612-burtynsky-mw13-collection-009

Manufacturing #15, Bird Mobile

Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, China, 2005

20070612-burtynsky-mw13-collection-010

Manufacturing #17, Deda Chicken Processing Plant

Dehui City, Jilin Province, China, 2005

Edward Burtynsky is considered one of Canada's most respected photographers. Born in Ontario in 1955, Burtynsky is a graduate of Ryerson University and Niagara College. His early exposure to the General Motors plant in his hometown inspired his ambition to depict global industrial landscapes. His imagery explores the link between industry and nature, finding beauty and humanity in the raw elements of mining, quarrying, manufacturing, shipping, oil production, and recycling.

In 1985, Burtynsky founded Toronto Image Works, a darkroom rental facility, custom photo laboratory, digital imaging, and new media computer-training center for the local art community.

Burtynsky's works have been exhibited in solo and group exhibitions across Canada, the United States, Europe, and Asia. His prints are housed in public, corporate, and private collections worldwide, and are included in 15 major museums around the world, including the National Gallery of Canada, the Bibliothèque Nationale, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Guggenheim.

Burtynsky has received numerous awards and fellowships, and has lectured at the National Gallery of Canada, the Library of Congress, and the George Eastman House. His images have appeared in various periodicals, including Art Forum, Art in America, Art News, Blind Spot, National Geographic, and the New York Times. He also sits on the board of directors for Toronto’s international photography festival, Contact.

Edward Burtynski

For 25 years I have created images about how our civilization has imposed itself upon and transformed nature. During the course of my work I have become anxiously aware of the impact our actions are having upon the world. As a husband and father, as an entrepreneur and provider, with a deep gratitude for his birthright in a peace loving, bountiful nation, I feel the urgency to make people aware of the consequences we could face. What we give to the future are the choices we make today.

For the past five years, I focused my attention on and made photographs about China. I began thinking about this formidable country as a subject around the time that construction began on the Three Gorges Dam. The voyages and resulting images I made during those years were as much about my personal need to understand the ecological events unfolding on our planet as they were about the powerful force China is now bringing to bear upon how the world does its business.

In my view, China is the most recent participant to fall prey to the seduction of western ideals, the promise of fulfillment and happiness. From my experience of living in a developed nation, the troubling downside of progress is something that I am sensitive to. The mass consumerism these ideals ignite and the resulting degradation of our environment intrinsic to the process of making things to keep people happy and fulfilled frightens me. I no longer see my world as delineated by countries, with borders, or language, but as 6.5 billion humans living off a single, finite planet.

—Edward Burtynsky, June 2007