20060914-decesare-mw12-collection-001

Mayra Hernandez, age 9, receives physical therapy at CIREC, a center that helps physically disabled children heal emotional trauma and learn to use prosthetics.

Colombia, 2004.

"I lost my leg but also my father and my grandparents. Someone knocked on the door and my papa went to open it. But before he reached the door, a bomb exploded and the bricks fell on him. It killed him, but I didn't know because I fainted. My whole body was asleep.

"People say that a guerrilla of the FARC [Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionaros de Colombia] left the bomb in the house next door to ours. If it was our neighbor, then she knew us. She left with her kids that morning, so they wouldn't get hurt. I don't know how she could do this knowing we were still there. They say it was because Vice President Francisco Santos was going to pass by. So when the soldiers who were bodyguards passed, the bomb exploded and some of them were injured. Some became deaf. But the ones killed were my papa and grandparents.

"I didn't think anything at first. I didn't know my father was dead. I didn't know that my leg was mush. When they brought me to Bogota, the doctors here told me that my leg was infected and it would kill me if they didn't amputate.

"When they told me that, I didn't want to live. I told them to let me die. You feel like you are the only one. You think of all the things you can't do.

"The surgeon who operated on me was very kind. She saved my life. The psychologist told me I could learn to walk again. She was right. Little by little you learn to do things again—new things, too. This weekend was the first time I was in a pool. I got in, and I learned to swim. It was fun.

"It is important for children who don't have a leg or an arm to know that they are not alone. In Colombia, the sad reality is there are many children like me."

20060914-decesare-mw12-collection-002

"Maria," age 16, lives in a home for former combatants sponsored by the Colombian Family Welfare Institute. She was 13 years old when she joined the FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionaros de Colombia) guerrillas.

Colombia, 2004.

"I come from Casanare. I lived there with my mom and three sisters. I worked for as long as I can remember, but what I hated most was working on the palm plantations. It was like being a slave, the pay is so little. I used to fight with my mother about it all the time.

"My boyfriend was with the guerrillas. He said, 'Come away with me. It will be better.' My older sister went, and so I followed her. Then my younger sisters followed me. My mother begged me not to go, but I didn't care. I wasn't afraid of combat. You get used to it. I loved the guerrillas. We were fighting for a better life for people like my family.

"I have a necklace. I don't wear it much now, but when I first got captured by the army and came here I wore it all the time. The necklace has a stone with a picture of Che Guevara. I wanted to return to the guerrillas, and I wore it to show everyone that I didn't want to be here. I still have it. It is like my memories of my sister and my comrades. They are good memories. But I don't wear the necklace anymore.

"I changed. I started going to school and to meet my mother. I realize how much we all broke her heart. At first I used to laugh at her. Now I think, 'Why was I so mean to her?' We started getting closer. Then when my older sister was killed in combat six months ago I started really thinking about how my mother would feel if I went back. I started to think about how I could help my family, and now I pray my other sisters can escape or get captured by the army and get out of all that.

"I don't believe anymore that war will make things better. Everyone has to make their own way, to struggle for their family and the people they love. I still believe in the things the guerrillas said we were fighting for. But I don't believe the war will get us those things, so I don't want to go back. When I see my mom cry for my dead sister, I just want to hug her and get a decent job, so I can help us all."

20060914-decesare-mw12-collection-003

Pregnant at age 13 with no family, "Roxana," age 15, began working in a brothel saloon to support herself and her baby.

Guatemala, 2001.

"My mother gave me away to a señora when I was a year old. The señora took good care of me. I stayed with the señora till I was 10. She died. Then I was all alone. I tried to go back to my mother, but she treated me bad, so I looked at the buses one day and got on one that said Chimaltenango. I didn't know anyone there, but I decided to go far away to find work.

"At first, I worked in a restaurant washing dishes, later in houses washing clothes. Then, when I was 12, I met an older man who wanted to hug me. He said he would take care of me. He became my husband. But after four months with him, I was pregnant and he left me.

"That is when I came here to work. I knew this place because I would pass it sometimes. The señora here was kind, and she let me come to work. She is indigenous too, and she gives me advice. She pays me 300 quetzaeles [$38.00] a month. I used to make only 100 quetzaeles [$12.00] a month washing clothes.

"Often I think I want to leave this life. Some men are abusive; others are kind or sad. No one stays. But leaving this life is difficult. I only studied to first grade, and now I need to buy milk for my baby. He's six months and eats a lot. The baby milk is very expensive.

"In the beginning, I thought I would give my baby away. But then I thought? I don't want to give my son away like my mother gave me away. I knew he would always be sad thinking of that. I don't have any dreams really. Well, to marry and have a happy family, but I don't think that will happen now."

20060914-decesare-mw12-collection-004

"Carolina," age 18, lives in a home for former combatants sponsored by the Colombian Family Welfare Institute. She joined the FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionaros de Colombia) guerrillas when she was 13 years old and lost her foot when she stepped on a landmine.

Colombia, 2004.

"My mother abandoned me when I was 9 years old. I stayed with my grandmother and went to school. I was studying in eighth grade when I just up and left and went with the guerrillas. I was 13 years old. On the one hand, it was because I liked the guns. I liked their uniforms. It was clear that people respected them a lot. And it was also because I felt so alone. My grandmother took care of me, but I still felt alone.

"I feel alone again now. A few days before this accident happened, they [the Colombian army] killed all the people from my unit. Well, not everyone was killed, but we had fierce combat and many friends died fighting. Some were captured and gave themselves up. The few of us who survived and escaped went to the outskirts of the city. That is where this happened to me.

"We knew there were landmines in the area to protect our supplies from the enemy, but we were not certain exactly where the landmines were. I heard something and ran and then I fell. When I stood up the mine exploded. I flew up in the air and hit a tree. The impact of hitting the tree almost killed me. That night they took me to a doctor. It must have been about 11:00. I didn't know that my foot was gone. They didn't want to tell me. They were afraid to. But the next day I realized, and when I did it was like everything went black. It hit me hard, and I tried to kill myself. But they found me with the knife and took it away from me.

"I cried and cried for three days without stopping. I never imagined anyone could cry so much or so hard. But there was nothing else I could do. They kept me in the camp for a while, but they couldn't keep carrying me, and my leg was getting worse. I had an aunt that they trusted and they brought me to her. They promised her that in three days they would come back and get me. But they didn't come. We waited and waited and my leg got very infected. My aunt got afraid because of the smell [it was gangrenous], and so this is how my family decided to turn me in to the army.

"Ever since then I've lived in a group home with three other girls who also used to be guerrillas. I can't say I repent my past life though I do want to leave it behind. You can't repent for loving people who loved and cared for you. The FARC [Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionaros de Colombia] was my family for many years. But I don't believe what they believe anymore. What good is the war? My friends are dead and look at me. Sometimes I still cry and think who will ever love me now. But I will get a prosthetic leg. When I learn to walk with it and wear pants no one needs to know that I don't have my foot."

20060914-decesare-mw12-collection-005

"Monica," age 16, stands before the door to her room in the brothel saloon where she lives and works.

Guatemala, 2001.

"I come from a very small village of peasants. Buses go there, but not many. It's a long, bumpy dirt road. There is no television in my village, only the radio.

"One of my uncles was in the army. But we were lucky the war didn't come to our village. My childhood was happy. I have no complaints. No bad things happened to me. Well, except that my father was a preacher and he abused all the girls in my family. He was drunk most of the time, and he beat my mom and us whenever he was drunk.

"The first time I was with a boy, it was a boy from the village. Luckily, I didn't get pregnant. My father would have killed me. I was 14. The boy wanted to marry me, but I don't want a man beating me like my father and telling me what to do. I don't want to be married ever. I would like to have children, but without a husband. They don't treat you well.

"It was an older cousin of mine who brought me here when I was 15. I've been here a year and now my sister is here with me too. I didn't know what the work was at first. They told me I was going to be a waitress. It was hard to be with these men.

"But I earn 600 quetzaeles [$74.00] a month from the owner of the bar, and I live here in the back. I don't know what the men pay. They give the money to the owner and later he pays me.

"My sister and I speak our language when we don't want other people to know something. I never put on a mini skirt. I like my traditional dress.

"Dreams? I don't have any."

20060914-decesare-mw12-collection-006

"Misrael," age 16, lives in a shelter for homeless children living with HIV.

Guatemala, 2005.

"My life turned bad when I was 11—that is when I started doing drugs. But before that, things were rough, too. My father was in the Guatemalan army. He and my mom were fighting all the time. My dad is the first one who got addicted to drugs. My mom left him for my stepfather when I was five.

"My father was murdered when I was seven and my uncles said it was my stepfather who paid to have my father killed. I don't know if it is true, but I went back to live with my mom even though I hated my stepfather. That is when I got deep into drugs. I was full of hatred. My parents tried to talk to me, but I didn't listen. I got deeper and deeper into drugs and finally after a month they kicked me out.

"I was 14 then, and I had nowhere to go. I began living with friends or just anyone I met. I felt upset that my parents kicked me out, but they told me not to come back if I didn't stop the drugs. I couldn't. I went first from marijuana, to cocaine, to crack.

"Finally, I went to look for my grandfather. He wasn't my real grandfather; he was my grandma's second husband. But my grandma had died and after this he went to live near the border with Honduras. I always liked him, so I went to find him. When I got there, I found out that he had a new wife. She was much younger than him. She was from Honduras. She used to give me drugs. That is when I learned that she was really a prostitute.

"I wasn't in love with her, but sometimes I was lonely. She would give me crack, cocaine, any drugs I wanted, just like that, for free. Well, not exactly for free. She wanted sex. She was 27, and I was 14. I would get drugged and then I didn't even remember what happened. I lived there for two years till I was 16. After that, I came back to the city. I was feeling sick. I don't know what is wrong. They tell me I have that sickness that kills you. I feel weak because of all that I've been through. But I hope maybe I don't have HIV."

Update: Since this conversation Misrael has been hospitalized with an HIV-related illness. He is no longer in denial about his status and is taking antiretroviral drugs.

20060914-decesare-mw12-collection-007

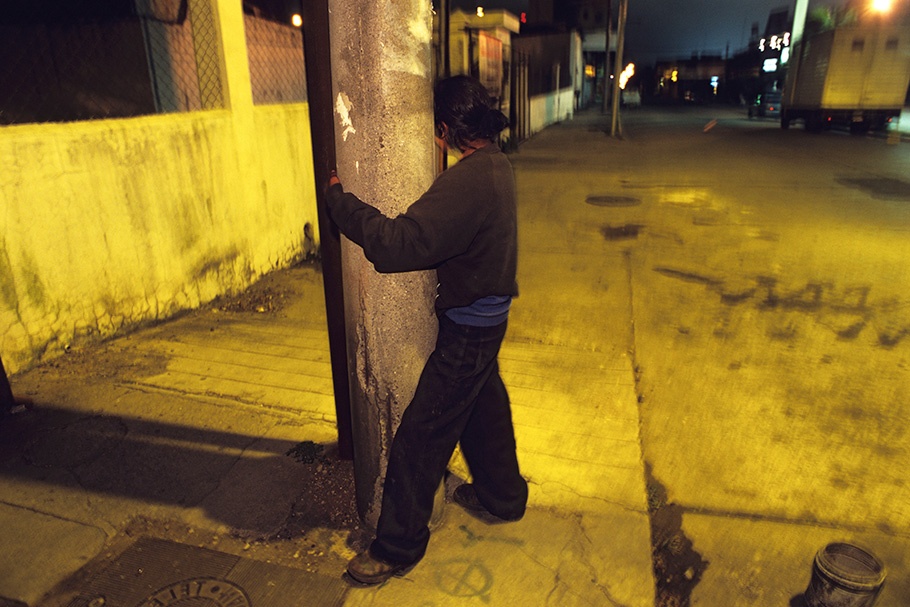

Cindy Paula, age 17, is a single mother who works in the red light district along the railroad line.

Guatemala, 2001.

"I was six months old when my papa left my mama. She only has me now, and my younger brother and sister, so as the oldest I have to help.

"Right now, my mom and I get along. But it wasn't always like that. The big problem was my stepfather. He beat me, and I got mad at my mom when she didn't stop him. So I left home at 14. I started living in the streets with other kids. The streets are hard. People always want something from you. The boys all want sex. In the end, they give you the cold shoulder. There are no real friends.

"I tried glue and solvent at first. Then I moved on to marijuana, cocaine, and crack. Sometimes I would have sex in exchange for food or drugs. I got so addicted I preferred drugs to food. Finally, I ended up in the hospital with cardiac arrest. The doctor told me I was going to die if I continued the drugs. I cried and cried. I was so scared. That is when I decided I had to stop.

"I made friends with a woman who worked as a prostitute at the railroad tracks. She was 20, and she told me I could make better money doing that than working in a factory and it was better than stealing or begging. She explained everything to me—how to use condoms, how much to charge, how to make my price a lot higher if someone looked sick or violent, so they'd go away.

"Even though I know it's not the best, for me it is the only way to get ahead. As a servant, I'd make 300 quetzales [$37.00 per month]. In a textile factory, I'd make 1,200 quetzales [$148.00 per month]. Here, I can make twice as much.

"But someday I hope I can leave here. You always have to hide things when you work in this. If someone where you live sees where you work then they spread gossip. I don't want my boy to grow up feeling ashamed of me."

20060914-decesare-mw12-collection-008

Nancy, age 24, and her six younger siblings were displaced after surviving one of Colombia's most brutal paramilitary massacres. In 2000, during three drunken days of mayhem, paramilitaries tortured and killed more than 40 villagers from El Salado. Nancy works with Women Life and Future, a support group for women who have been affected by the war.

Colombia, 2005.

"I was 16 in 1997 when the paramilitaries arrived with the first list of names. One of the people on it was my neighbor, Domingo Mena, another was the schoolteacher. They only killed four people that time, but it shocked us. We couldn't believe what we had seen with our own eyes. Then, in 2000, the paramilitaries came back with another list of names. This time they ate and drank while they tortured and killed almost 40 people in the town square. They said they were killing guerrillas.

"In Montes de Maria, people are accused of collaborating with the guerrillas. If an armed person comes to a civilian and says, 'make me coffee,' I make the coffee if I value my life, so they don't kill me. But when the paramilitaries were coming, the guerillas left. And who remained in the town? Unarmed peasants. And who got killed? The peasants.

"Fear is something that invades your heart so that it becomes like your most trusted friend. Once fear exists the smallest thing can activate it. Today, in El Salado, it is the Colombian army that asks for favors. Now, if someone does a favor for the soldiers, then in five days you might be found dead in a bag. Fear has made the civilian population victims, but silence has made them collaborators in their victimization.

"The war is a business fed by ignorance, fear, and acts of rage. If I am a man and my father rebukes me, I pick up a gun to get even and feel superior. Sometimes it is that simple. Rage blinds you. It makes you make crazy mistakes. The desire for vengeance is one of the roots of the violence we live with.

"Thankfully, we've had a lot of support and psychological help in El Salado. At the time of the massacre, I wanted the electric chair for every one of them. Now, I would ask the paramilitaries who committed the massacre, 'What made you do this? What gives you the right to take life?' Maybe they will answer that they were following orders. Then I would ask, 'How would you feel if this had happened to you, to your family?' I don't want to make them suffer this; I do want them to at least imagine what it would feel like to be us.

"If they cry and wail and tell me they are sorry, this will not convince me. My family and I have cried more tears than the people who did this ever can. I believe in actions more than words. But if there is a process that breaks the silence, ends the fear, and makes them show a genuine change of heart, with time I hope I can accept that. I don't know if that is justice. But life teaches you tolerance."

20060914-decesare-mw12-collection-009

"Rosario," age 19, lives in the streets and sometimes stays at the Casa Alianza shelter in Guatemala City. A social worker confirmed the truth of her story, but was not hopeful that Rosario would press charges against the men who raped her.

Guatemala, 2001.

"I left home when I was seven. My father beat me a lot, and so did my mom. I used to sell candies in the streets. Sometimes I would steal, but mostly I would beg. For a little while I was with a gang, Mara Salvatrucha. I would sell myself as a prostitute for drugs.

"I used to sleep in an abandoned warehouse here. Lots of street children go there. But I don't go there anymore because of what happened. Nine months ago I was there sleeping. The police came. It was 6:30 in the morning, and they came into the building where we were. They told all the women to get up and that they were going to search us for drugs. Then they took us to the bathroom and told us to take off all our clothes.

"At first, I refused. I told them they would not want this to happen to their own kids. But they threatened to rape us all if we didn't do as they said. When they didn't find any drugs they let the other women go.

"Then one of them laughed in my face. He grabbed me and raped me. Another cop raped my friend Jennifer, who is 15.

"Then they told us to get dressed, and they left. A little while later they came back, bringing us ham and tortillas to eat. They told us not to tell anyone and threatened us if we did.

"But we told Casa Alianza. The medical exam proved that we were raped. And now Casa Alianza is helping us make a case against the police who did this to us."

20060914-decesare-mw12-collection-010

"Tomas," age 15, lives in a home for former combatants sponsored by the Colombian Family Welfare Institute. He joined the AUC (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia) paramilitary forces when he was 11 years old.

Colombia, 2003.

"I left my house because of my mother. She and my father argued a lot. One day, she was screaming at him. She kept screaming. It scared me, and I ran to hide. But I saw it. She lit my father with fire. The flame caught on his clothes. He was burning, and he died. After that when she was angry, she told me she would do the same to me. I was eight, I think. I don't remember. Do I have to remember?

"The main thing is I was scared, and I hated her. Sometimes I went home, but I stayed away a lot. I was afraid. That is when I met the paramilitaries. They were kind. Even though I was little, they said I could stay with them, and I didn't have to do anything. I was the favorite. They bought me nice clothes, everything I needed, gifts, and food. I was so happy with them. I loved them. They told me not to think about my mother. They told me they would always protect me.

"Later, bad things happened. I saw them kill people, a lot of people. They told me they had to. I didn't like it. Sometimes I felt so angry I wanted to kill someone, but then I would feel afraid. They told me not to worry. I didn't have to do any of that. I would close my eyes.

"They were my family. I would never have left them. But one day the army came. They saw how small I was, and they captured me and brought me here. I begged them to let me go back. At first, they kept us locked in here. I wanted to escape and return to the paramilitaries.

"Now that I have been here for almost a year, I think I want to stay. School is hard. I don't understand things. At first, I didn't like to be around so many women, but there is one girl I like. I met her when we took a trip to a farm. She was very kind and pretty, too. I would like to see her again. They tell me if I stay here maybe I can see her again."

20060914-decesare-mw12-collection-011

"Maria," age 18, lived in this the abandoned building before her friend Ronel convinced her to move to the Our Rights Shelter and begin HIV treatment.

Guatemala, 2005.

"I remember my papa, but my mother was a prostitute. I never knew her. She gave me to my father. I had a stepmother, but she beat me constantly. So I left and went to live in the streets when I was 12. My father found me and left me at Casa Alianza and told them he couldn't take care of me. But I didn't stay. I ran away to the streets.

"It was a girl I met there that showed me how to get high. First, I used glue. Later, it was crack. I would beg for money. Sometimes the people would give a few coins, sometimes they said, 'Don't be lazy, work.' But I would always find someone to give me something, food or a little money. With the money I got more drugs. Sometimes I would have boyfriends for drugs. I feel ashamed to say it. I don't even remember most of the things that happened.

"Then I had a boyfriend for almost two years. I can't remember how old I was, maybe 14 or 15, or how old he was. He's the father of my baby, but we split up when Luis Alfredo was born, and he's a year old now.

"Then I met Ronel again. He was my friend in the streets before. The night he came, he wanted me to go to a shelter. He brought me there. He said I should get off drugs for Luis Alfredo. He said they would help me get off drugs and get medicine. They gave me an exam for HIV, and they told me I had it. I don't know if Luis Alfredo has it, too. We are waiting to test him soon."

Update: In May 2006, I visited Maria again in Guatemala. She told me that in January she ran away from the shelter for two weeks and during that time she got pregnant again. She is back living at the shelter and following a regimen of antiretroviral drugs to prevent HIV transmission to her unborn child. She still doesn't know if Luis Alfredo is HIV positive.

Donna DeCesare was born in New York City. After completing an MPhil degree in English Literature at Essex University, England, she began working as a freelance photographer, writer, and videographer.

DeCesare is the recipient of fellowships and grants, including the Dorothea Lange prize, the Alicia Patterson fellowship, the Mother Jones International Photo Fund grant, and the Soros Individual Project fellowship. In 2003, she was named a fellow of the Dart Society for the Study of Journalism and Trauma, and in 2005, she completed a Fulbright Fellowship in Colombia.

Her photographs have been published in news and arts magazines, and exhibited in national and international exhibitions. Her photo reportage for the website Crimes of War won a top award in the NPPA Best of Photojournalism, and her work on U.S. and Latin American gang violence has won photojournalism awards.

She has worked as a videographer and producer on projects for PBS, Discovery, and The Learning Channel. Killer Virus, her first video assignment, won an Emmy Award in 1995.

In 2002, DeCesare joined the journalism faculty at the University of Texas, where she teaches documentary photography and video. She is also a member of the advisory board of the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas.

Donna DeCesare

Over the last several years—on self-assigned projects and in collaboration with UNICEF—I have been documenting Central American and Colombian children living with a burden of fear and stigma. Whether they are living with HIV, surviving as prostitutes, or struggling with the physical and emotional scars of war, the fact that they are children does not save them from being treated as outcasts or blamed for situations over which they have little control.

Children affected by the war in Colombia, whether former combatants or children maimed or displaced, all face varying degrees of social exclusion—from ridicule to social cleansing or retribution. In Guatemala, it is not uncommon to hear that HIV is a curse from God. Children suffer taunts and bullying from classmates, but also hostility from teachers who would exclude them from their classrooms. Those who want to clean up “HIV carriers” target street children, already vulnerable to vigilantism. While economic desperation leads some children to brothels, there are disturbing subtexts of incest, abandonment, or semi-enslavement in these testimonies that demand public outrage.

As children in Guatemala and Colombia know, showing your face while speaking honestly can get you killed. And yet, they also crave recognition. As soon as they spotted my camera, they were eager for fame or immortality. “Oh, take my picture,” they said, But a moment later, their expressions turning sober, they would add, “Just please don’t show it here.”

Any illusion that photographers can control where or how our images appear dissolves in the age of the Internet. An image that exists in a public sphere can be instantly copied and distributed whether or not its publication is intended or officially sanctioned. How to depict suffering and injustice without exposing victims to further stigma or harm has become much more difficult. The ubiquitous reach of the Internet penetrates even remote areas of Guatemala and Colombia.

Knowing that I couldn’t control local exposure of my images, I needed to find a way of working that would protect the children’s identities, allay their fears, and empower them to speak truthfully about their lives.

When I was beginning the project, a conversation with Ellen Tolmie, the UNICEF director of photography, stuck with me. We’d been talking about the need for children, especially those who feel imprisoned by stigma, to have a context in which they can exercise control. Later, when a child asked if he could pick a different name to accompany his photographs, it occurred to me that he was really asking to share control. This inspired me to look for ways to make the image-making process collaborative. My conversations with the children became like a brainstorming game. In this playful dance of posing and waiting for a spontaneous gesture, an expression of candor, or an image that provided context, we learned to trust each other and they were able to share their secrets.

—Donna DeCesare, September 2006