20060914-leong-mw12-collection-001

Groups of Falun Gong followers numbering in the hundreds and sometimes thousands openly practice spiritual breathing exercises. The following spring, the government began a nationwide suppression of the Falun Gong movement.

Beijing, 1998.

20060914-leong-mw12-collection-002

Neighbors play mahjongg while their houses are demolished.

Beijing, 1996.

20060914-leong-mw12-collection-003

Shanghai, 1997.

20060914-leong-mw12-collection-004

In the intensely anti-American political climate during the months following the NATO bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, young Chinese continued flocking to fast food outlets like KFC and McDonald's.

Beijing, 1999.

20060914-leong-mw12-collection-005

Sandy, 25, sells body piercings, stuffed toys, and other gifts at her shop. Her boyfriend stays at home playing an online computer game seven hours a day.

Beijing, 2003.

20060914-leong-mw12-collection-006

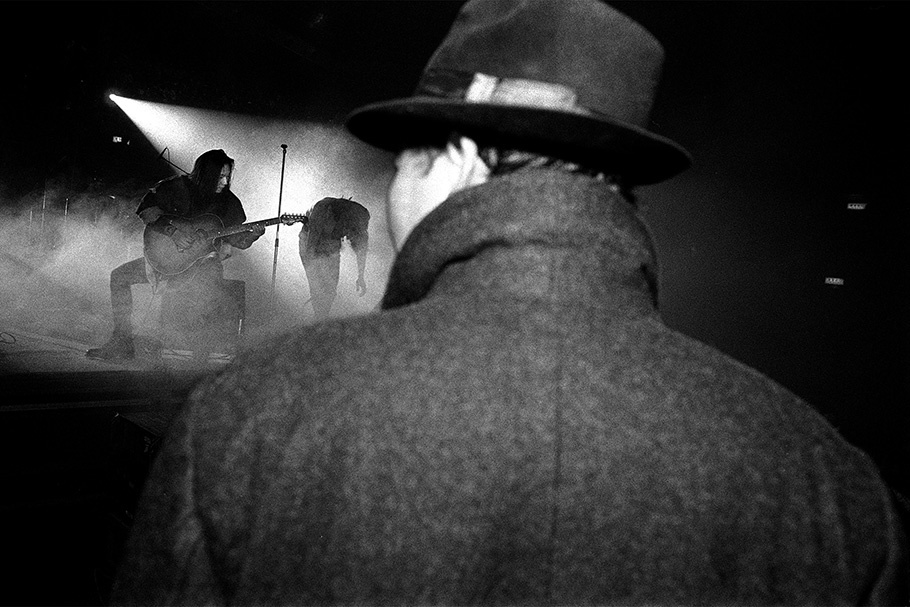

A plainclothes policeman monitors a show by the metal band Tang Dynasty.

Beijing, 1992.

20060914-leong-mw12-collection-007

A drug user breaks small paper pods of heroin on a crisp 100 yuan note, where he sifts it before smoking it.

Lanzhou, 2002.

20060914-leong-mw12-collection-008

Ancestor worship ritual during the Lunar New Year. Food offerings and the burning of symbolic paper money are gifts to the spirit world.

Taishan, 1990.

20060914-leong-mw12-collection-009

Migrant workers float from city to city looking for work and sleep in the train station until they can find jobs, usually on construction sites.

Beijing, 1992.

20060914-leong-mw12-collection-010

A young woman tries on a rented wedding dress at a photo studio. She is already married, but only now has enough money saved up to have pictures taken.

Shenzhen, 1999.

20060914-leong-mw12-collection-011

Dang Jianjun, 21, lost both arms in a factory punch press accident on August 13, 1999 at 2:00 a.m., eight hours into the overnight shift. An average of 31 such accidents per day occurred that year in Shenzhen.

Shenzhen, 2001.

Mark Leong is a fifth-generation American-Chinese whose family emigrated from Guangdong Province to California over 100 years ago. After graduating from the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies at Harvard University in 1988, he was awarded a George Peabody Gardner Traveling Fellowship to spend a year taking photographs in China.

In 1992, he returned to China as an artist-in-residence at the Central Academy of Fine Art in Beijing, sponsored by a fellowship from the Lila Wallace-Reader’s Digest Foundation. He subsequently decided to make his long-term home in Beijing, where he has lived since, observing what changes and what remains the same in the world’s most populous country.

In 2003, Leong joined the Redux Pictures photo agency. His photos have appeared in Time, Fortune, The New York Times, Business Week, The New Yorker, Stern, and National Geographic. He has received grants from the National Endowment of the Arts and the Fifty Crows International Fund for Documentary Photography. His book China Obscura won a special citation from the Overseas Press Club for photographic reporting in magazines and books in 2004.

Mark Leong

I first came to China in 1989, the day after the Tiananmen crackdown. My idea was simply to photograph daily life, a ground-level record of a year in my ancestral homeland. With the democracy movement stamped out, I assumed that China would return to a state of isolation as the Communist Party reconsolidated control. I traveled the countryside by bus and train, taking pictures of farmers and schoolchildren, imagining that their lives would stay the same for years to come.

During my second year-long trip to China in 1992, I realized how wrong I had been. Deng Xiaoping had given his blessing to private enterprise, so instead of glum socialism, I encountered free-for-all capitalism in a nation trying to transform itself as fast as it could. In 1989, products like motorcycles and air conditioners were rare luxuries that often had to be smuggled into the country. Three years later, however, these items were not only for sale, they also were being produced locally, along with, according to the labels, clothes, electronics, and sports gear—almost everything in the world.

I also didn’t expect that more than a decade later, I would still be taking pictures in China, compelled by the surge of constant change. But while many of my assignments for Western publications have covered the colorful commercial explosion that has captured the world’s attention, my personal photos have explored the darker realities outside media spotlight.

A sense of broken trust has come to define the relationship between China’s citizens and its government, beginning with Tiananmen in 1989. With the shift toward capitalism in 1992, the Chinese people were left to fend for themselves in a new economy. Since then, China’s gains toward economic superpower status have also been marked by loss—of paternalism, of ideology, of guaranteed welfare. Meanwhile, the Communist Party retains its monopoly of political power, and the gap between burgeoning free markets and stagnating personal freedoms continues to widen.

This project documents the lives of ordinary individuals as they attempt to navigate this altered landscape. In the mayhem of economic growth, some have found new opportunities while others have been further marginalized—herded out of their homes or made into commodity laborers in the name of progress. The old Communist Party—which dominated every aspect of Chinese life for half a century—no longer exists. The ideological and spiritual void left in its place is palpable at all levels of society, as people search, and wait, for something to fill it.

—Mark Leong, September 2006