20060914-vanlohuizen-mw12-collection-001

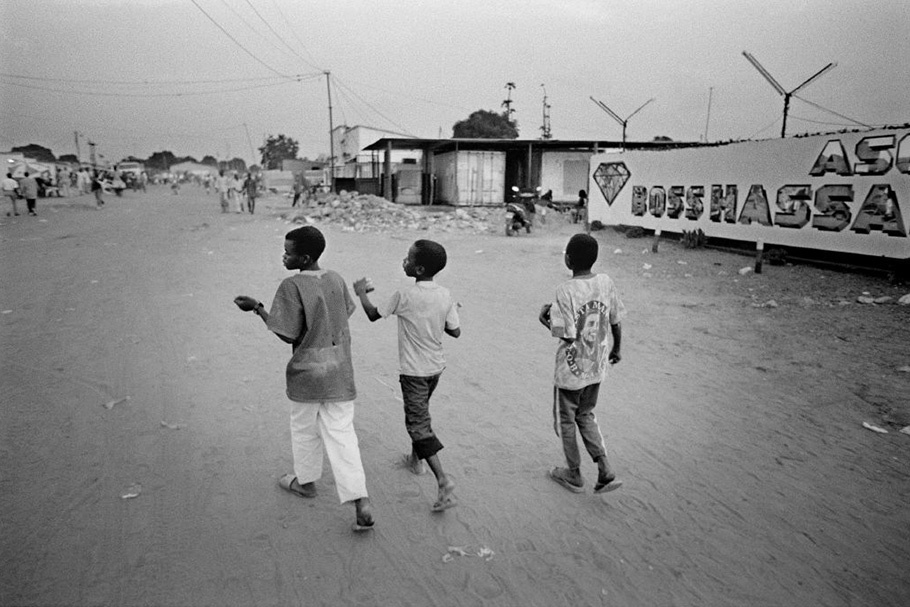

Cafunfo is one of the richest diamond towns in the country.

Angola, 2004.

20060914-vanlohuizen-mw12-collection-002

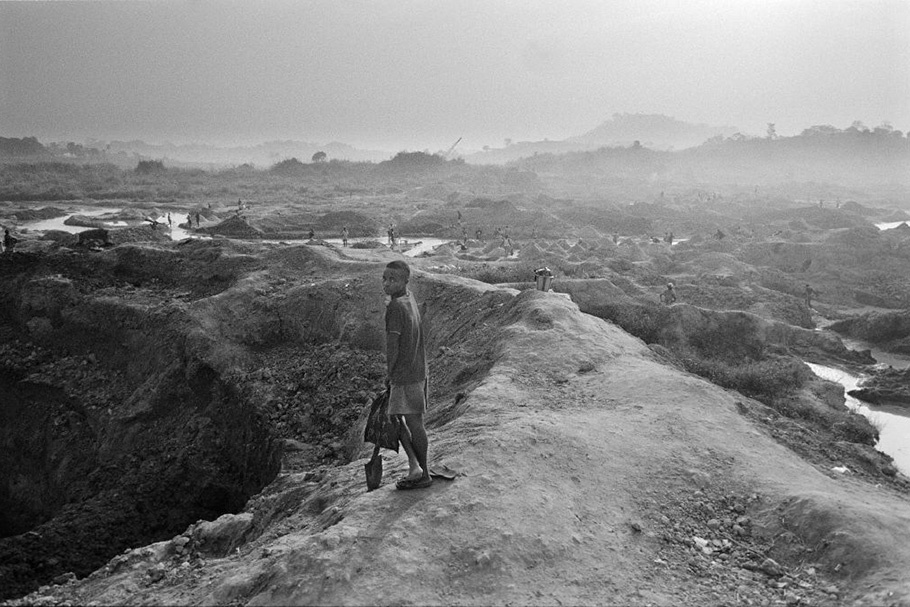

Mines in Koidu.

Sierra Leone, 2004.

20060914-vanlohuizen-mw12-collection-003

Mines in Koidu.

Sierra Leone, 2004.

20060914-vanlohuizen-mw12-collection-004

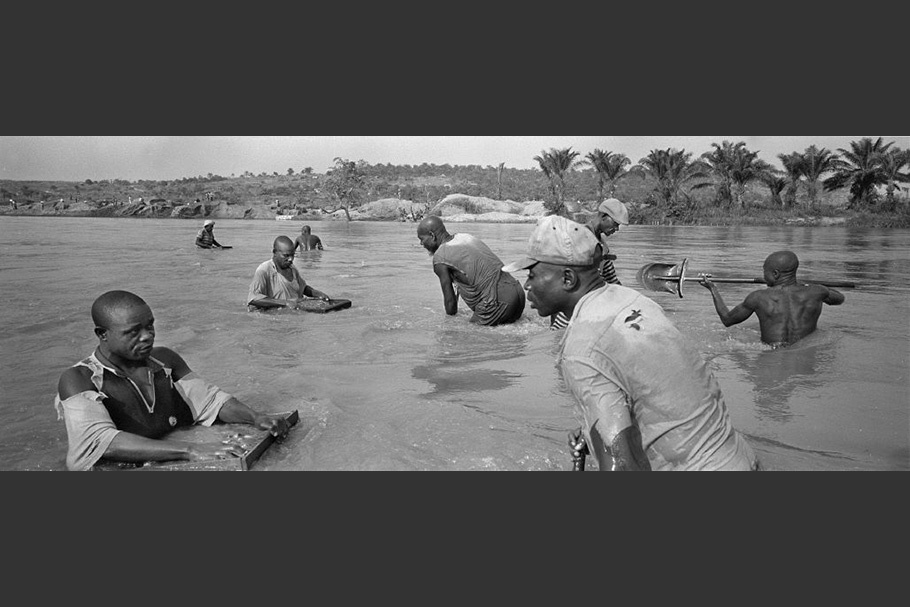

Washing the gravel in the river near Mbuji-Mayi.

Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2004.

20060914-vanlohuizen-mw12-collection-005

Diamond divers at work in the river Cuango.

Angola, 2004.

20060914-vanlohuizen-mw12-collection-006

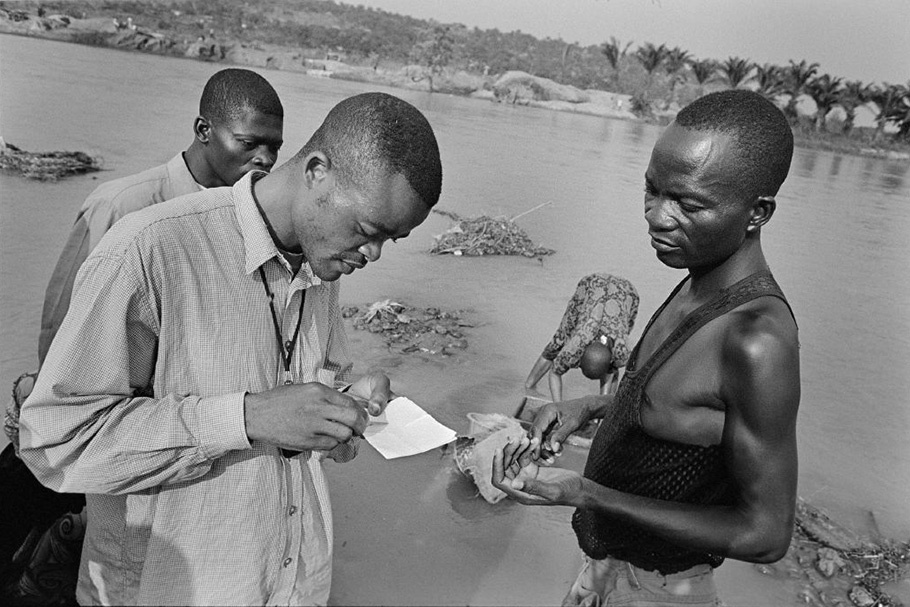

Diamond buyer at the river in Mbuji-Mayi.

Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2004.

20060914-vanlohuizen-mw12-collection-007

Funeral of a miner in Mbuji-Mayi. Many miners die because they drown or sand walls collapse.

Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2004.

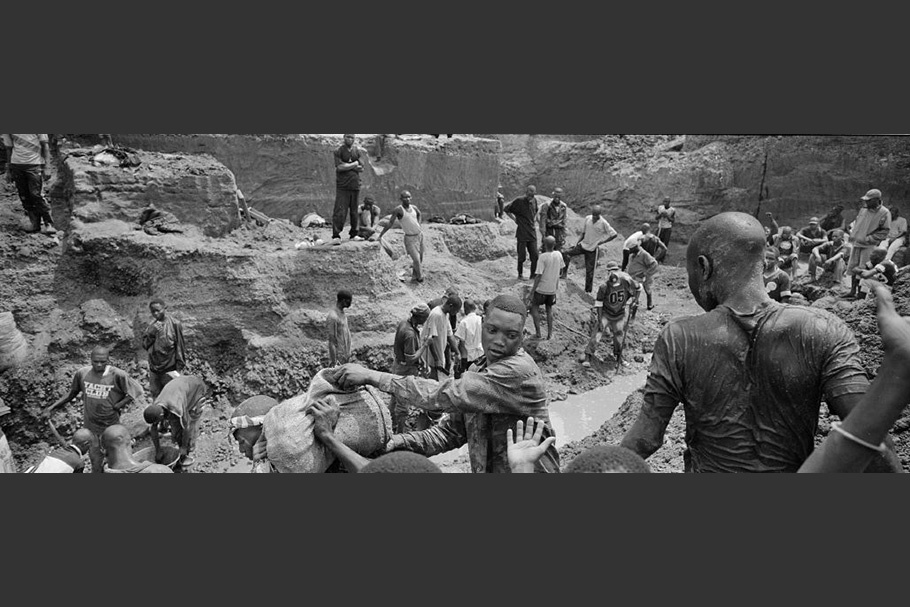

20060914-vanlohuizen-mw12-collection-008

Carrying gravel out of the mine at Bakwa Bowa.

Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2004.

20060914-vanlohuizen-mw12-collection-009

Diamond found at the Sewa river.

Sierra Leone, 2004.

20060914-vanlohuizen-mw12-collection-010

Diamond market in Mbuji-Mayi.

Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2004.

20060914-vanlohuizen-mw12-collection-011

Surat is the main polishing center for diamonds in the world. About 70 to 80 percent of the world diamond production passes through here.

India, 2004.

20060914-vanlohuizen-mw12-collection-012

The exchange for rough diamonds in Antwerp.

Belgium, 2004.

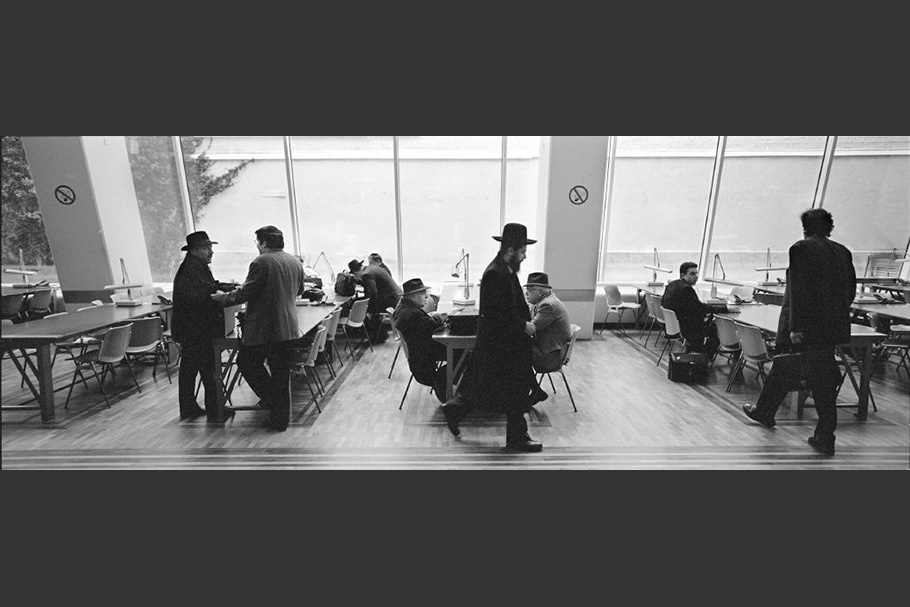

20060914-vanlohuizen-mw12-collection-013

The diamond area in Antwerp.

Belgium, 2004.

20060914-vanlohuizen-mw12-collection-014

An exclusive jewelry store on Fifth Avenue in New York.

United States, 2004.

20060914-vanlohuizen-mw12-collection-015

An exclusive party in London.

England, 2004.

Kadir van Lohuizen, a freelance photographer based in Amsterdam, Holland, began traveling and taking pictures after graduating from high school in 1982. By 1988, he was working as a professional freelance photojournalist. More recently, he has worked on documentary films for television, examining the gas industry in Siberia in 2001 and the ongoing conflict in Colombia in 2002.

He has been awarded several grants throughout his career; most recently, he received a Katrina Media Fellowship from the Open Society Foundations to cover the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Van Lohuizen has earned numerous honors, including the Zilveren Camera 1997, the highest Dutch award in photojournalism, and two World Press Photo awards.

His work has been published in newspapers and magazines throughout the world, and exhibited widely, including at FOAM in Amsterdam and at Visa Pour L’Iimage in Perpignan, France. His most recent book, Diamond Matters, was published by Mets and Schilt Publishers in 2005.

He is a member of Agence VU in Paris.

Kadir van Lohuizen

In the 1990s, I covered the fighting in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), Sierra Leone, and Angola, conflicts that were often dismissed as tribal wars, the final convulsions of the Cold War. By degrees, however, these conflicts turned into struggles over diamonds.

The diamond deposits, for the most part, were controlled by the Angolan and Sierra Leonean rebels, who used the gems as a means to buy weapons. Governments got in on the act, and the terms “blood diamond” and “conflict diamond” were born.

In time, pressure was put on the diamond industry and the relevant authorities to create a certification system to guarantee that only conflict-free diamonds came on the market. Worried by any threat to its image, the industry bowed to public opinion and entered into negotiations with the various regulatory authorities. In 2002, the Kimberley Agreement was signed by a large number of the exporting and importing countries. The agreement reduced smuggling and made the industry more transparent. Today these countries, on the whole, are at peace, and officially rebel movements no longer play a role in diamond exploitation.

Yet working conditions remain appalling. Profits are enormous but very little flows back to the people. They are chased off their land and given little, if any, compensation. A fair trade agreement for diamonds would be the ideal solution, with profits being shared by all in the industry and diamond workers’ rights being protected.

Until recently, the South African company De Beers had a monopoly on the diamond market and was able to dictate prices. But given the large diamond reserves in the world, a collapse of the market and tumbling prices are not inconceivable. Such a collapse would not benefit the African countries, where mineral resources such as diamonds, if used for the common good, can fund reconstruction and economic development.

A year ago, in cooperation with the Netherlands Institute of Southern Africa, I returned to the African countries I had covered during the fighting to follow the diamond trail from mine to ultimate consumer. These photographs attempt to picture the whole industry by depicting the workers, financiers, dealers, and the people who buy and wear diamonds.

—Kadir van Lohuizen, September 2006