20001004-chang-mw04-collection-001

New immigrants often flock to one of the twenty unregulated employment agencies in the area. Each paper slip in the area represents a job offer which is usually either in a restaurant, a garment factory, or a construction site.

20001004-chang-mw04-collection-002

More than 300 garment factories, often located in hidden lofts and garrets, manufacture clothes for most of the nation's major retailers.

20001004-chang-mw04-collection-003

Former employees of Silver Palace Restaurant in Chinatown picket outside the restaurant to seek compensation.

20001004-chang-mw04-collection-004

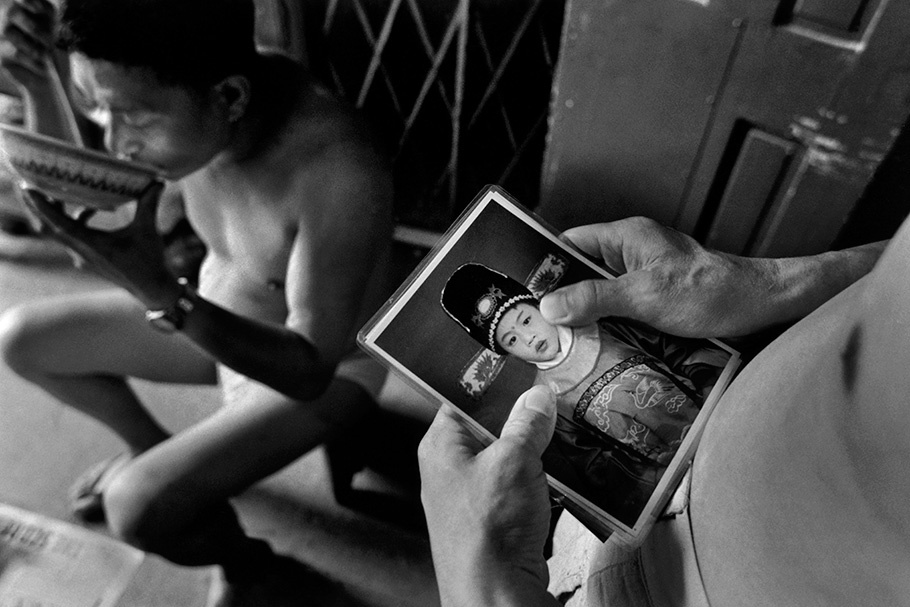

Having not seen his son for more than five years, this immigrant can only watch his kid growing up in photographs, which his family sends him regularly.

20001004-chang-mw04-collection-005

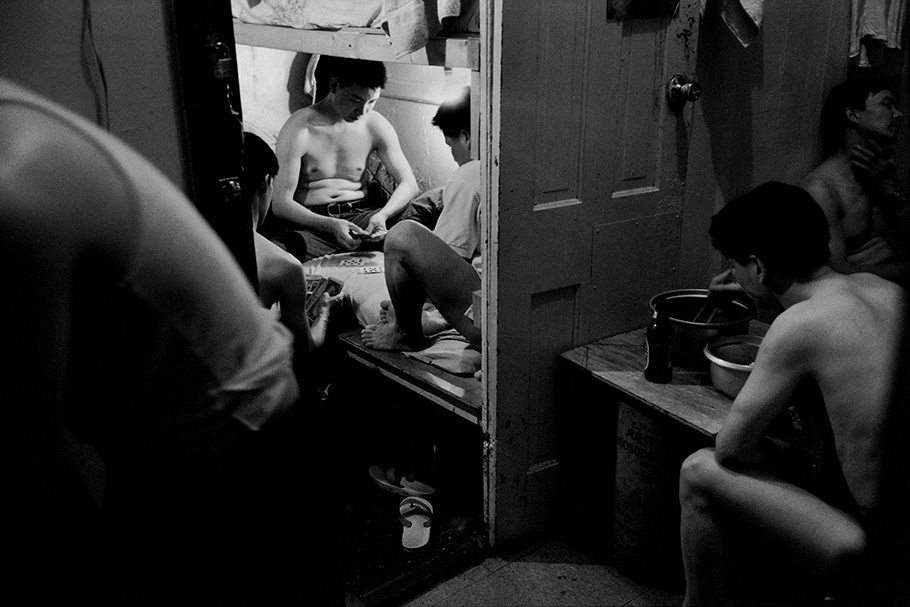

Living in airless cubicles on Bowery in Chinatown, Fujianese spend their lonely evenings playing cards with people from the same village.

20001004-chang-mw04-collection-006

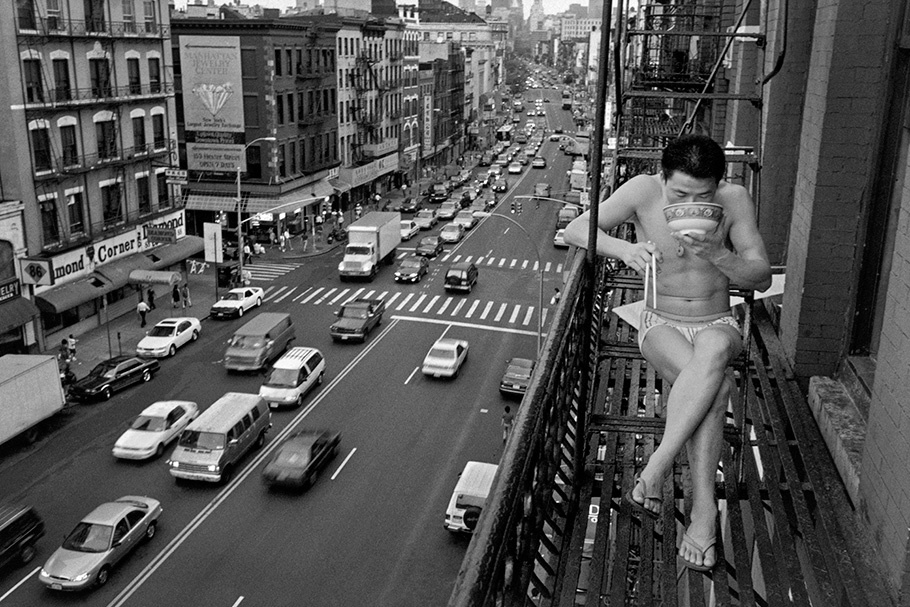

Avoiding blistering summer heat, this newly arrived immigrant eats his supper on the fire escape oblivious to the cars and pedestrians rushing by.

20001004-chang-mw04-collection-007

When the temperature reaches 100F, their squalid tenement, which is subdivided into 32 units, of which only four have windows, turns into an unbearable oven. Subsequently immigrants sleep on fire escapes to avoid heat.

20001004-chang-mw04-collection-008

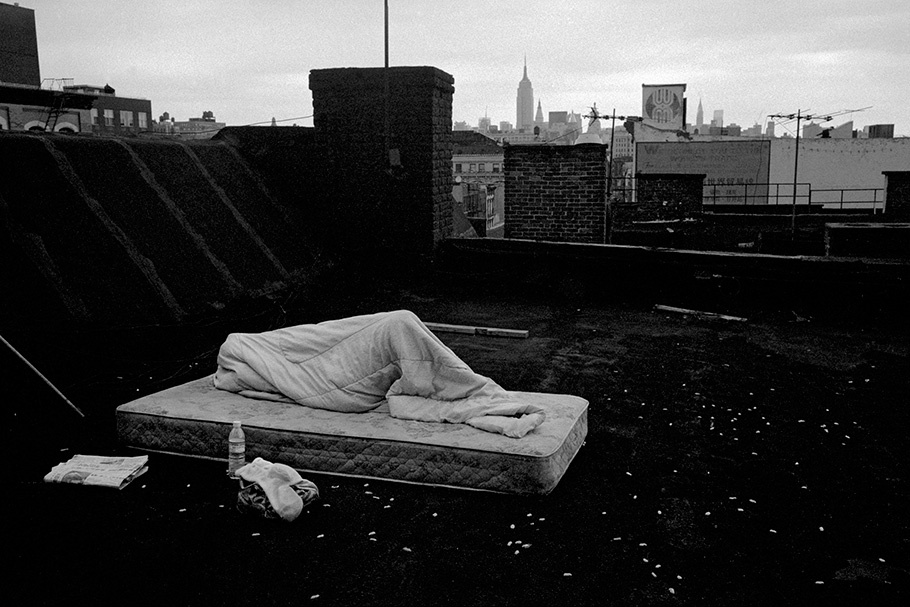

Unemployed and with no one to turn to for help, this immigrant ends up sleeping on the roof of a building for the whole summer.

20001004-chang-mw04-collection-009

American mainstream society seems out of touch and out of reach to this immigrant who cannot speak English and feels that he is trapped on an island within an island.

20001004-chang-mw04-collection-010

Fujianese manage to save every penny they earned from substandard wages by sharing food with the same villagers so that they can pay off their debts.

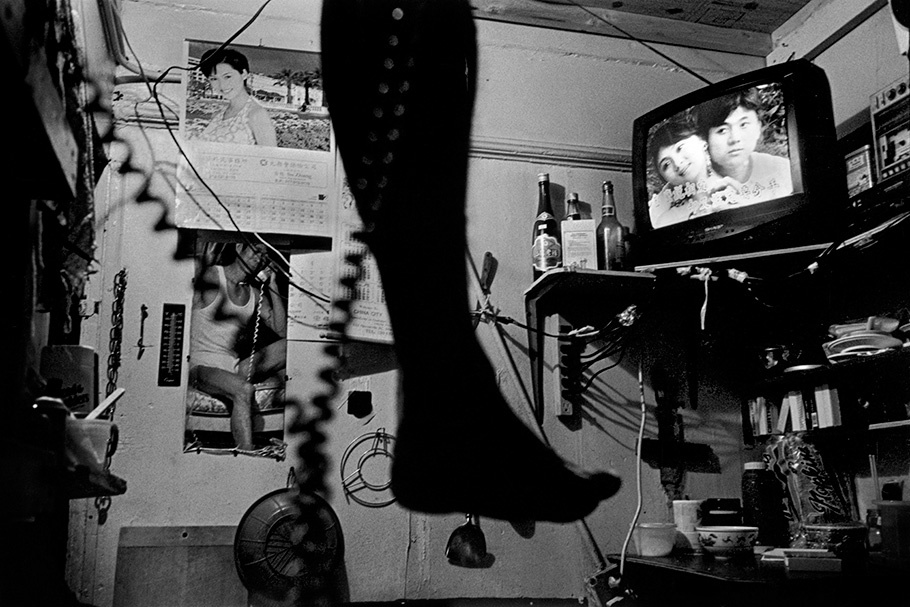

20001004-chang-mw04-collection-011

An immigrant watches a Chinese soap opera on his day off.

After graduating from Soochow University in Taiwan with a Bachelor of Arts in English Language and Literature, Chien-Chi Chang continued his studies at Indiana University, completing a Master of Arts in Education. He was staff photographer at the Seattle Times (1991–1993) and later at the Baltimore Sun (1994–1995). He became a Magnum nominee in 1995. Since then he has completed a project on Chinatown for National Geographic. He has also published photographs in the New York Times Magazine, the New Yorker, and GEO. Chang published “The Chain” in Photographers International, which conveyed the stories of life among 700 patients in a Taiwanese asylum. Chang was also the recipient of the W. Eugene Smith Memorial Fund in Humanistic Photography and was awarded the Visa D’Or in magazine photography at the Visa pour l’Image International Festival of Photojournalism in Perpignan, France. He was the Missouri/NPPA 1999 Magazine Photographer of the Year. Chang also won 1999 World Press Photo’s first place award for Daily Life Story.

Chien-Chi Chang

When I was growing up in a farming village in central Taiwan, I heard endless stories about New York’s Chinatown. They told of an immigrant community so self-contained that it was virtually a nation unto itself. It was a place where anyone could get rich, if only they worked hard enough.

I took a job in the United States in 1991 and discovered a different reality. Tens of thousands of poor Chinese place themselves in the hands of unscrupulous smugglers who often starve and torture them during the long sea journey to the United States. Once here, the immigrants are delivered into a life of indentured servitude and extortion, and soon discover that it would take years to earn enough to pay off the $50,000 smuggling debt. They work seven days a week in Chinatown’s restaurants and garment factories for extremely low wages, and must face the resentment from the legal immigrants.

I asked myself what life must be like for these illegal immigrants when even I, an educated man with a U.S. work permit, had experienced that ache of loneliness, the sting of racial prejudice, the alienation of culture shock?

In 1996 I went to live alongside the “invisible immigrants” who left their families behind in China to sleep in shifts on rows of shared bunk beds crammed into roach-infested Bowery tenements. I profiled my bunkmates and next door neighbors, who worked 16 hours each day, then paid for the right to spend the remaining eight sleeping in a bed that would be occupied by someone else as soon as they left for work.

There is no political agenda behind this project. I only hope to illustrate how in this modern, global age, we cannot separate ourselves from the sufferings of those in other countries, no matter how distant, for, all too soon, the consequences spill over onto our shores.

In some ways, the plight of these illegal immigrants echoes my own history. A family of seven, we lived in a small village and shared a single bed. My parents worked in nearby rice paddies. Before I became a teenager we moved to a large city in Taiwan. Our lives were displaced by the move. We lived in a two-room apartment with another family of six. We faced an uncertain future in a city teeming with thousands of others trying to eke out an existence in the hopes of a better life.

Whether the switch is from rural to city or to a land thousands of lonely miles away, the forces that propel the poor to emigrate, despite the uncertain outcome, is a universal story and one I feel compelled to document.

—Chien-Chi Chang, October 2000