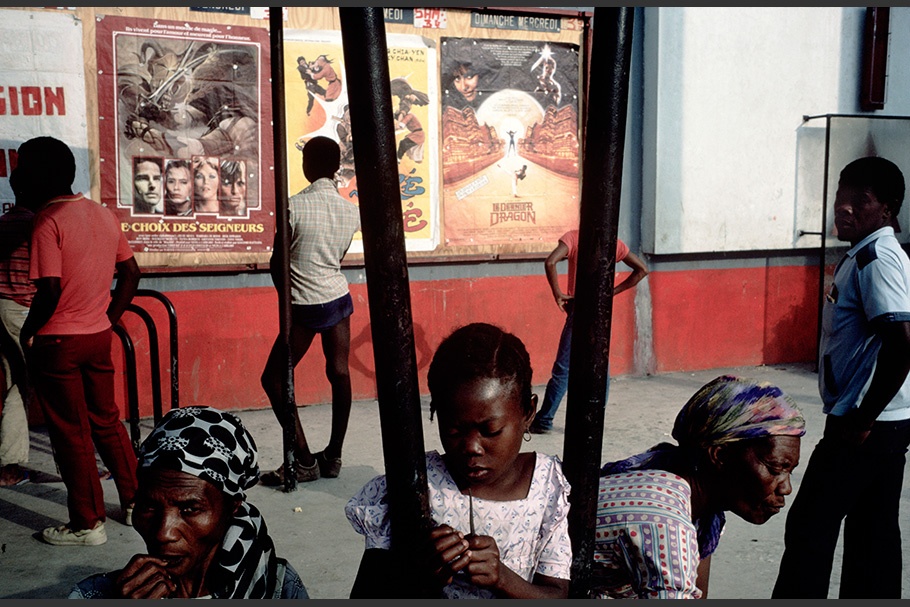

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-001

Port-au-Prince, Cité Soleil, 1986.

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-002

Port-au-Prince, 1986.

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-003

Etroits, La Gonave, 1986.

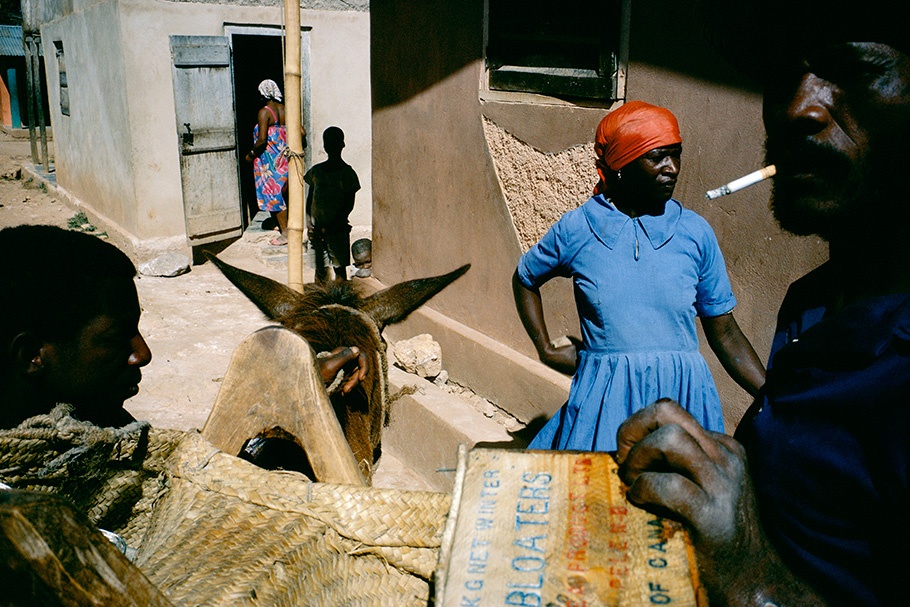

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-004

Bombardopolis, 1986.

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-005

Near Torbeck, 1987.

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-006

Port- au-Prince, Cité Soleil, 1987.

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-007

Port-au-Prince, 1987.

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-008

Arcahaie, 1988.

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-009

Bombardopolis, 1986.

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-010

Memorial for victims of army violence. Port-au-Prince, 1987.

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-011

Anse a Galets, la Gonave, 1986.

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-012

Port-au-Prince, 1987.

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-013

Baie de Henne, 1986.

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-014

Saut d'Eau pilgrimage, 1987.

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-015

Port-au-Prince, 1988.

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-016

Cap Haitien, 1987.

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-017

Cap Haitien, 1987.

20001004-webb-mw04-collection-018

Port-au-Prince, 1994.

Alex Webb was born in San Francisco, California, in 1952. He majored in history and literature at Harvard University and studied photography at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. He attended the Apeiron Workshops in 1972 and began working as a professional photojournalist in 1974. Webb joined Magnum Photos as an associate member in 1976, becoming a full member in 1979. His photographs have appeared in such publications as the New York Times Magazine, Life, GEO, Stern, and National Geographic. Webb has photographed in the United States, the Caribbean, Latin America, Europe, and Africa. He has published four books: Hot Light/Half-Made Worlds (1986), Under A Grudging Sun (1989), From the Sunshine State (1996), and Amazon: From the Floodplains to the Clouds (1997). He has also created a technology-mediated artist’s book, Dislocations (1998–9). Webb received a New York Foundation of the Arts Grant in 1986, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in 1990, and a Hasselblad Foundation Grant in 1998. He won the Leopold Godowsky Color Photography Award in 1998 and the Leica Medal of Excellence in 2000. He has exhibited widely both in the United States and Europe.

Alex Webb

I took the majority of these photographs during two years, 1986 to 1988, following the demise of the Duvalier regime. It was a period initially called "Haiti Libere," reflecting the optimism that suffused the country as Baby Doc Duvalier departed. But ultimately it turned into a time of tragedy, as the army and paramilitary gunmen killed dozens of voters at the polls, destroying the elections of 1987 and paving the way for the army-anointed candidate, Leslie Manigat, in 1988.

Cycles of brief optimism followed by long-term despair seem to recur throughout Haitian history. Since Manigat's accession, Haiti has suffered a series of coups and counter coups, an invasion by the United States, and a series of elections marred by fraud and coercion. The high hopes engendered by the possibility of a savior for Haiti, the priest-turned-politician Aristide, have been dimmed for some by parliamentary factionalism and by the fact that the stalwarts of his party, Lavalas, have not been particularly receptive to the co-existence of alternative points of view. Since the accession of Manigat, I have returned five times to Haiti to photograph. The country remains wracked by dire poverty, a nearly non-existent formal economy, and a crumbling infrastructure. The existence of many Haitians remains marginal, even if some of them now feel they have a champion in Aristide.

It remains to be seen what will transpire with the presumed accession of Aristide this next year. Some of the poor may now have a voice in this leader, but will any other voices be allowed to be heard? Can the unrelenting cycles of Haitian history be broken?

The last words of my introduction to my book Under a Grudging Sun remain all too pertinent: "But I am certainly the wrong person to predict the future of sad and beguiling Haiti. I should perhaps just walk, and watch, and wait..."

—Alex Webb, October 2000