20081120-noorani-mw15-collection-001

A young girl sits on the broken wall of an informal glue factory where workers process waste leathers to make glue in Hazaribagh near the Buriganga River in Dhaka.

Hazaribagh, Dhaka’s leather processing zone, is in the middle of one of the most densely populated residential neighborhoods. About 194 leather processing industries operate here and freely dump untreated toxic wastes directly into the low-lying areas, rivers, and natural canals. The pollution is seriously affecting the lives of thousands of people, bringing the area to the brink of an environmental disaster.

20081120-noorani-mw15-collection-002

Men and women boil waste leather to make glue in the Hazaribagh area near the Buriganga River in Dhaka.

20081120-noorani-mw15-collection-003

Standing on a pile of garbage on the embankment of the river, children burn the garbage to expose metals and collect them with a magnet. Garbage that cannot be recycled any further gets dumped into the severely polluted Buriganga. It is not uncommon to see children as young as 7 years old combing the garbage dumps.

20081120-noorani-mw15-collection-004

A woman jumps over a puddle of chemical and leather waste. She works making glue by boiling waste leather pieces.

20081120-noorani-mw15-collection-005

Nawab Ali, 12, carries buckets of glue manufactured from waste leather, while Jabar, 14, fills buckets from a tank in the Hazaribagh glue factory near the Buriganga River in Dhaka.

Nawab Ali came to Dhaka about a year ago from a village in the Rangpur district in the north of Bangladesh. He first worked in a dry fish–processing factory, but quit because of the poor pay and bad smell. His job in the glue factory is not much better. He earns about 60 taka for a 13-hour work day. His parents work as day laborers for a similar amount, but only when there is work.

20081120-noorani-mw15-collection-006

Sikendar, a fisherman, catches Taki Mach, a tough fish that thrives in polluted water. “No, it’s not difficult to sell these fish,” he said. “Water is polluted, but not fish. They are fresh fish from the river. When you eat, you can see fresh, white meat.”

20081120-noorani-mw15-collection-007

After bathing, a woman and a girl collect murky water from the Buriganga River at Ayena Ghat on the outskirts of Dhaka.

Each day Dhaka dumps thousands of tons of raw sewage into its rivers and other bodies of water, making them extremely polluted for human consumption and use. Yet many poor migrants living on the outskirts of the city have little choice but to use the polluted water.

20081120-noorani-mw15-collection-008

Untreated sewage being released into the Buriganga River. Each day Dhaka’s 12.6 million people produce about 3,200 tons of solid waste, most of which goes into the river. And each day up to 40,000 tons of untreated tannery waste is released directly into the river.

20081120-noorani-mw15-collection-009

A young boy washes vegetables in the contaminated water of the Shitalakhya River on the outskirts of Dhaka. The vegetables will be sold in the local market.

Thousands of people living on the banks of rivers like the Turag and Dhaleshwari as well as the Buriganga and its tributaries are at risk of serious health hazards including intestinal and skin diseases. The water from Buriganga’s three tributaries—the Narai, Debdholai, and Balu—looks like discarded engine oil. Rivers that used to serve as a lifeline for people living on the city’s fringes today are nothing more than open sewers.

20081120-noorani-mw15-collection-010

A woman takes a bath in the Buriganga River in Dhaka.

20081120-noorani-mw15-collection-011

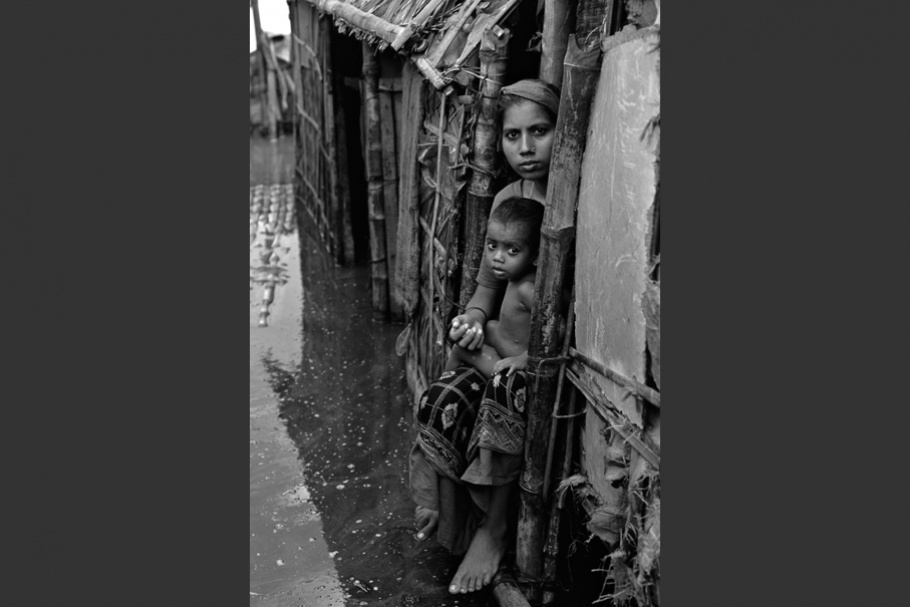

A woman with her child sits in the doorway of her shack in a bamboo slum on the outskirts of Dhaka. Her home is built directly over a pool of chemical waste from a nearby tannery plant. The only way she and her children can get out of the house is by wading through this toxic water.

20081120-noorani-mw15-collection-012

Noorun Nehar, 15, looks through a hole in the curtain enclosing a battery-recycling workshop. Like thousands of others, she survives off the waste materials dumped on the banks of the Buriganga. She has been breaking apart and recycling batteries for three years, earning 300 taka per week.

Shehzad Noorani has a deep interest in social issues that affect the lives of millions of people in developing countries. He has covered major stories resulting from man-made and natural disasters in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Iran, Iraq, Sri Lanka, and Sudan. Other assignments for agencies like UNICEF have taken him to over 30 countries in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

His photography has been exhibited and featured in major international magazines and publications around the world. Noorani received a grant from the Mother Jones International Fund for Documentary Photography for “Daughters of Darkness,” his photography project on the lives of commercial sex workers in South Asia. He has also received an honorable mention from National Geographic’s All Roads Photography Program for “Children of Black Dust.”

Shehzad Noorani

This is a story about the Buriganga, a river that flows through Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. It is a local story with huge international implications. The Buriganga has always been a hub of commercial activity, busy, vibrant, and full of life, but never really clean. Today, the pollution in the river is at its worst.

Dhaka’s industries produce about 40,000 tons of untreated toxic waste daily. Its 12.6 million people produce another 3,200 tons of solid waste each day. The industrial waste and approximately 80 percent of the city’s sewage are released directly into the river, making much of the Buriganga biologically dead. The river has become so polluted that the water has turned black and thick like glue. Lacking government services, thousands of people living along the river have little or no choice but to use this highly contaminated water to wash, bathe, and even drink.

Bangladesh is a country of poor people, except for a few industrialists who recognize and exploit conditions to make huge profits. Labor is cheap and environmental regulations are weak. Some of the world’s largest garment and leather industries thrive in Bangladesh, free to dump their toxic waste into its rivers.

These polluting industries survive on orders from big Western manufacturers, taking shelter behind a self-serving argument: since the countries in the West have been industrializing and polluting for centuries, it is only fair that poor countries should now have the right to do so. The idea that developing countries need to pollute to escape poverty is just an excuse for moving polluting industries from one place to another.

We live in a global village, connected with each other in every possible way. We understand that bad environmental practices in one part of the world can have fatal consequences for people in other parts of the world. To allow industries in developing countries to pollute is not just wrong, but criminal. It does not make sense to control emissions only in the developed world and let developing countries pollute indiscriminately.

What is happening in Bangladesh is happening in countries like India and China on a much larger scale. Developing countries are responsible for about one-third of the world’s greenhouse-gas emissions, but experts predict that if the pace of industrial growth continues, by 2100 they will emit almost three times more than their developed counterparts. According to a study by the University of California, China has already surpassed the United States as the world’s largest carbon polluter. If we don’t improve environmental practices in developing countries, everyone will suffer.

—Shehzad Noorani, November 2008