20081120-wiedenhofer-mw15-collection-001

Destroyed Shacks next to the Mexican-US border.

Tijuana, Mexico. April 2007.

20081120-wiedenhofer-mw15-collection-002

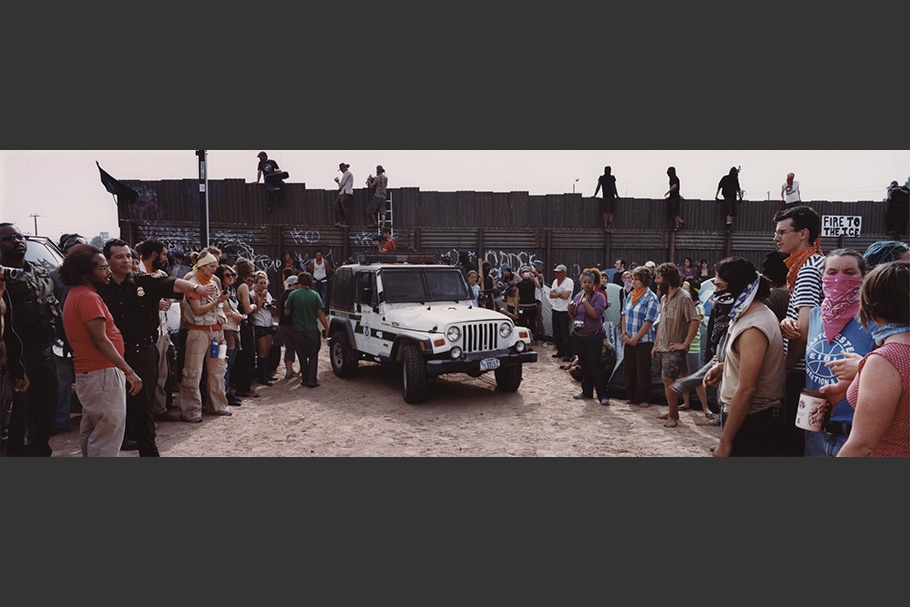

U.S. Border Patrol officers negotiating with activists who had put up a protest camp on both sides of the border. The officers wanted to make sure nobody entered the United States from the Mexican side during the protest.

Calexico, California. November 2007.

20081120-wiedenhofer-mw15-collection-003

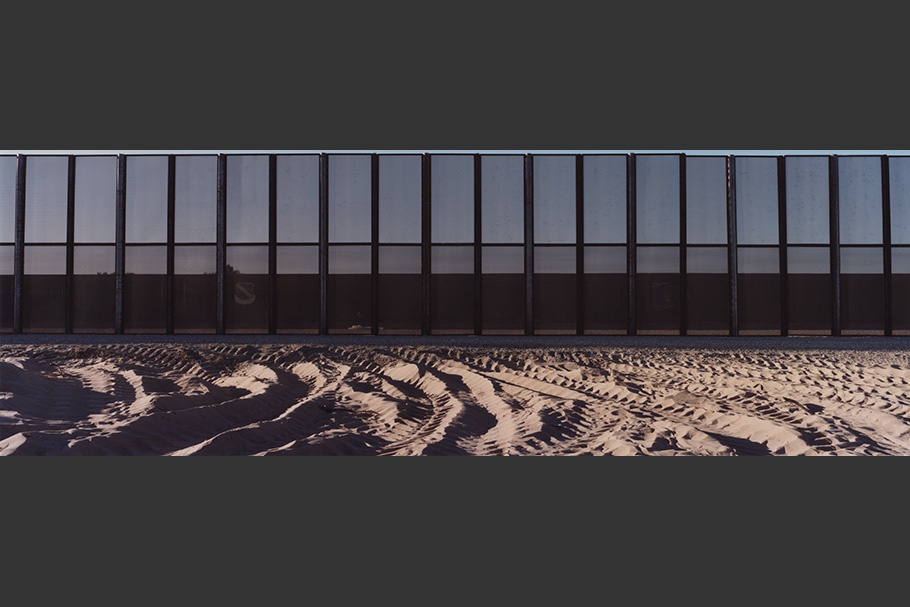

Newly erected fence and old metal wall on the U.S.–Mexico border.

San Luis, California. November 2007.

20081120-wiedenhofer-mw15-collection-004

Newly erected metal wall. An additional fence will be built 15 meters away from the wall. The column marks the actual border line.

San Luis, California. November 2007.

20081120-wiedenhofer-mw15-collection-005

Antifence protesters visiting a cemetery near Holtville, Arizona, where immigrants are buried. They died in the Sonoran desert while trying to enter the United States. The white crosses were put up by the Border Angels, an NGO that provides help for immigrants.

November 2007.

20081120-wiedenhofer-mw15-collection-006

Old and new border fence.

Tijuana, Mexico. April 2007.

20081120-wiedenhofer-mw15-collection-007

The Mexican-US border in Nogales, Sonora Mexico.

April 2007.

20081120-wiedenhofer-mw15-collection-008

Mexican migrant waiting near the border to cross into the United States at night.

Tijuana, Mexico. May 2007.

20081120-wiedenhofer-mw15-collection-009

Mexicans walking along the border in Tijuana. Behind them is the newly constructed concrete barrier and the old red metal wall.

April 2007.

Kai Wiedenhöfer, born in Germany in 1966, studied photography at the Folkwang School in Essen and Arabic in Damascus, Syria. Since 1989, his work has focused on the Middle East. He has received numerous awards, including the Leica Medal of Excellence, the Alexia Grant for World Peace and Cultural Understanding, World Press Photo Awards, the Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography, and, most recently, the Fuji Euro Press Award and the Getty Grant for Documentary Photography. He has published two books with Steidl, Perfect Peace (2002) and Wall (2007).

Kai Wiedenhöfer

I photographed the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. It was the most exciting and positive political event I have ever witnessed. This firsthand look at history in the making moved me deeply. It became a formative experience that years later caused me to react with shock and concern at the erection of the separation barrier in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. I photographed this new barrier between 2003 and 2006.

Now I am expanding my photographs of borders into a more comprehensive project to show that walls and fences are no solutions to today’s global political and economic problems. The U.S.–Mexico border is part of that project.

A barrier is a proof of human weakness and error, the inability of people to communicate with each other, to understand and settle differences. The simplest reaction to perceived problems is to build a barrier: to cut oneself off from others, to separate oneself from the threat outside.

Approaching a border raises tensions. We avoid them or try to leave them behind as fast as we can, though we constantly run up against them. Borders create stress, even fear. They run along ideologies, rich and poor, religion and race. Their significance is not just geographic, but psychological. They disfigure our thoughts as well as our landscapes. Without realizing it, we adopt an attitude in defense of borders: those on the outside are bad, we on the inside are good.

Globalization promises to dissolve borders. Yet its reality is deceptive: it enlarges markets but also insecurity in the world. While capital moves freely, people don’t. Many are unable to benefit from economic globalization, and the gap between rich and poor is widening. The U.S.–Mexico border is an example of a divide between the haves and have-nots. By barricading its southern border, the U.S. government is trying to keep have-nots out.

I want to show the conflict that is inherent in borders: on the one hand, we long for unconditional, absolute boundlessness. On the other hand, we feel lost in the boundlessness, and want to separate, distinguish ourselves, our culture, our community.

While fundamentally documentary in character, the project aims to illuminate the psychologies of borders, raise questions, and expose our experiences. Through these images, we should recognize ourselves, not as mere spectators in the erection of barriers, but as participants, sometimes unwilling, but participants nonetheless. While borders are a shield, they are also a cage, trapping even as they appear to protect.

—Kai Wiedenhöfer, November 2008