20040610-bartletti-mw09-collection-001

Bound to El Norte

Teotihuacan, State of Mexico, Mexico.

September 11, 2000.

Each year, en route to the United States, thousands of migrants like this Honduran boy stow away through Mexico on the tops and sides of freight trains.

20040610-bartletti-mw09-collection-002

Misery's Company

Tegucigalpa, Honduras.

July 24, 2000.

Vultures and children compete for scraps at a Tegucigalpa garbage dump. For many impoverished Honduran children, this dump is their last hope before they seek to escape the slow death of poverty by stowing away on northbound freights.

20040610-bartletti-mw09-collection-003

Orphaned and Addicted

Tegucigalpa, Honduras.

July 20, 2000.

Richard Alberto Funez, 10, waves a toy pistol and acts like a tough guy to the amusement of his buddy Alexis Joel Sanchez, 10. Hundreds of addicted homeless orphans roam the streets of Tegucigalpa scavenging for food and begging for money.

20040610-bartletti-mw09-collection-004

A Sad Farewell

Tegucigalpa, Honduras.

July 22, 2000.

Maria Marcos, 74, sadly recalls the day she pleaded with her 16-year-old grandson not to attempt the harrowing journey through Mexico on freight trains. But Enrique had made up his mind, saying, "I'm going to find Mami." Maria gave Enrique $7.00: all the money she had.

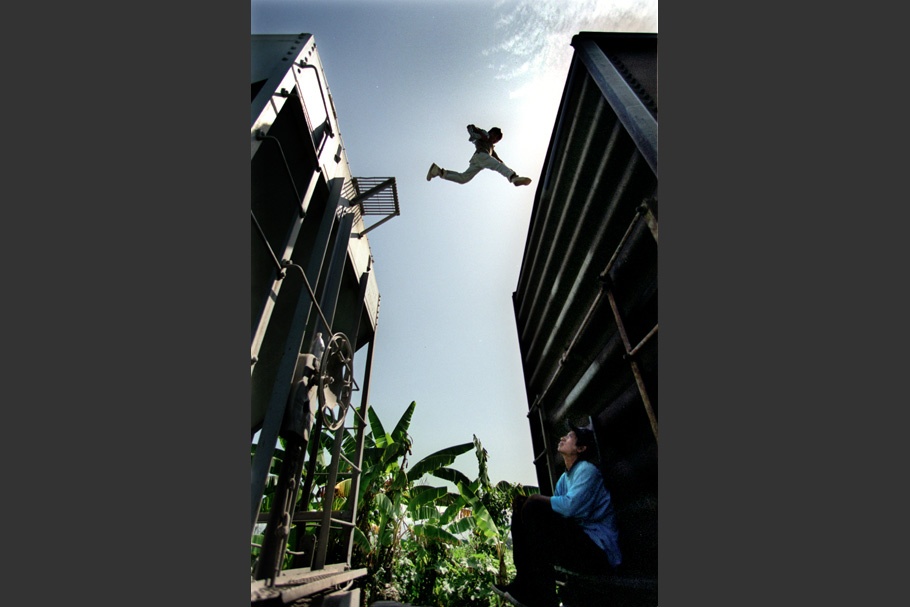

20040610-bartletti-mw09-collection-005

Soaring

Mapastepec, Chiapas, Mexico.

August 5, 2000.

Twelve-year-old Denis Evan Contrarez makes a daredevil leap between freight cars. Denis was left behind with a sister in Honduras when their mother went to California for a higher paying job. He hopes to find her in San Diego.

20040610-bartletti-mw09-collection-006

El Tren Peregrino: The Pilgrim Train

Chiapas, Mexico.

September 6, 2000.

Mexican authorities call freights crowded with migrants El Tren Peregrino (The Pilgrim Train). Undocumented Central Americans use cargo trains as a way past highway checkpoints in the southern part of the country.

20040610-bartletti-mw09-collection-007

Chiapas Racers

Chiapas, Mexico.

August 3, 2000.

A Mexican boy and girl race their horse alongside a freight train. This rare moment of joy was applauded by those riding atop the moving train.

Don Bartletti has been a photojournalist with southern California newspapers for 32 years. For the past 21 years, he has worked for the Los Angeles Times. Over his career, Bartletti has covered stories throughout California, Mexico, Central America, South America, and most recently, in Iraq and Afghanistan.

As a resident of San Diego County since high school, Bartletti is concerned with the viewpoints of migrant farm workers and borderland issues. Hundreds of his photographs on the subject have appeared in the Los Angeles Times and other newspapers, and in exhibits across the nation and Mexico. One exhibit toured seven major institutions in the United States, including the Smithsonian, the Ellis Island Immigration Museum, and the Museum of Tolerance.

Bartletti has received more than 50 awards, most notably the Pulitzer Prize for “Enrique’s Journey”, his six-part series on migration from Latin America to the United States. He has also earned the Robert F. Kennedy Award, the Polk Award, the Scripps-Howard Foundation Award, and the Sidney Hillman Foundation Award.

Don Bartletti

Don Bartletti wants to be invisible. He wants you to see through him and his art, to fix upon the images he has created and to ask: “How can such things be?” He credits this vision of photography to the late documentary photographer, Dorothea Lange. “I don’t want readers to necessarily dwell on how I did it,” he says. “In documentary photojournalism, I believe the subject, not the photographer, should be the number one author of the photo.”

Nowhere is this vision clearer than in Bartletti’s photos for “Bound To El Norte.” A boy loses his mother and sets out on a perilous journey to find her. In the vast movement of people from Central America and Mexico, Enrique is one of 48,000 children who come to the United States alone each year. Many are looking for their mothers, who went north seeking work.

Bartletti’s opening picture cries out: How can this be—a lone boy on top of a rolling freight train? It is dangerous and a little eerie. All lines of sight—the train, the tracks, the power lines, the youngster’s vision, and Bartletti’s camera—are focused on a single perspective: the future. What does the future hold? It’s not at all clear. There is fog ahead and a curve.

How can this be? Now Bartletti is in a garbage dump. “One of the more horrible places I’ve ever been.” Children forage for food. Hands blackened by slime, they pick up stale bread and eat it. Sleek, dark buzzards soar overhead, defecating on everyone.

Bartletti took remarkable risks to photograph and report this story. He followed the route from Honduras, through Mexico, and across the Rio Grande taken by Enrique, a Honduran teenager who eventually found his mother in North Carolina. Where Enrique walked, he walked, nearly 100 miles. Bartletti braved thieves, street gangs, and corrupt cops, just as Enrique did. Many of these children are beaten and robbed along the way; girls are raped. Where Enrique rode freight trains, Bartletti rode freight trains, more than 1,200 miles. Many of the children lose arms, legs, hands, or feet when they slip under the wheels climbing aboard; some fall off the top and die.

“I saw one kid get knocked clean off the train. Among stowaways, the train through the Chiapas jungle is legendary; they call it ‘The Beast’. The challenge was to convey a sensation of speed and motion in a still picture. I preset my camera: the focus, the shutter speed. Then I hunkered down with both eyes on the hazard and one finger on the shutter.”

Another photo captures a migrant riding between two boxcars, “I’m staring down from the roof of the next car. Antonio spreads his arms and grips the bar between the two ladders. For two brief seconds, he shuts his eyes, leans his head back, and opens his mouth. I don’t know if he’s moaning, screaming, or praying. I can only hear the wind and the rumble of the racing train.”

Bartletti’s favorite: the hand of a poor peasant reaching out to place an orange into the hand of an even poorer child speeding past on a train. “It’s a split second in time but the photograph preserves a moment of kindness between strangers.”

—From the editors of the Los Angeles Times