20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-001

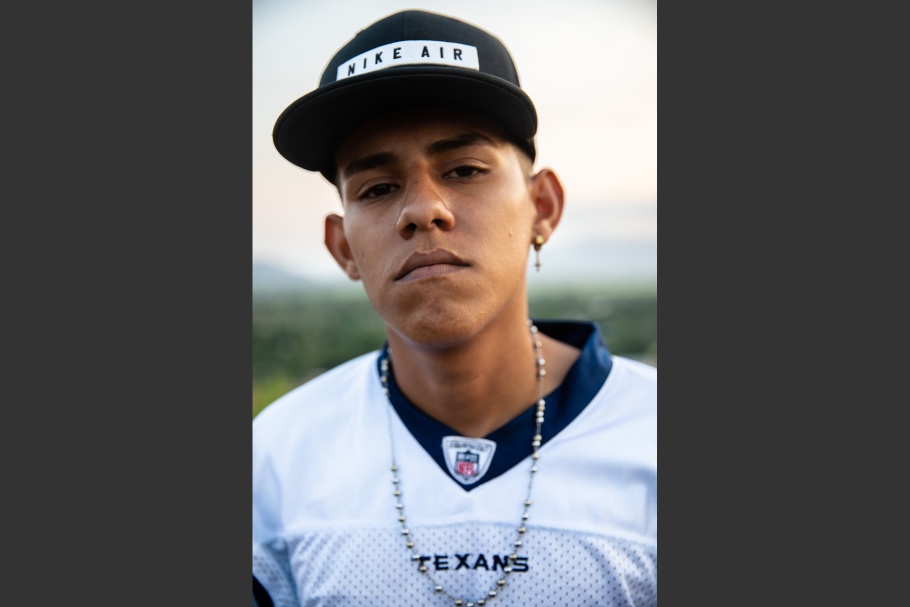

“Luis asked me for direction. I told him, ‘Man, it’s your picture. How do you want the old you to remember the young you?’ He blinked hard and breathed, and his face reset. The thing is, Luis is hilarious and isn’t ever not laughing. But his expression, this face he chose, didn’t line up with the laughs. There was more to it, I felt then and I feel now. The funniest kid from the hardest place suddenly without smile. Luis is Moises’ best friend, and he misses his big brother who left.” —Tomas Ayuso

San Pedro Sula, Honduras, April 2018.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-002

In the barrio, despite the trauma and chaos, there is still beauty. There are mothers doting on their babies, uncles teaching nephews how to kick penalties, and grandmas passing down secret family recipes. Luis, who stayed behind, watches over Moises’ daughter after Moises left for the United States. Standing behind Luis is Cindi, the baby’s mother.

San Pedro Sula, Honduras, April 2018.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-003

Luis laughs while talking to Moises on FaceTime. Moises had made it to the United States border. He’d ridden atop the train 2,000 miles by himself, poised to leave behind the pathos he was born into. Moises had broken from the short, fated life he was meant to suffer at the edge of San Pedro.

San Pedro Sula, Honduras, April 2018.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-004

Moises laces up behind a gang safehouse. Even though he’s not in a gang himself, he grew up among kids who chose to enlist, either voluntarily or by force. Moises is surrounded by the culture that comes with gang life. And where that culture dwells, death is never too far.

San Pedro Sula, Honduras, August 2017.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-005

“Tavo had asked his son Moises to flee the country while he could: ‘I tell him, Baby don’t dress like a fucking gang member. He doesn’t listen. I don’t know if you know this Tomas, but the police here don’t care if you’re in a gang or not. They’ll kill you either way, dump your body in the sugar cane and let the crocodiles take care of the rest. My Moises is a good boy, I raised him good. But he’s surrounded with the homies and that’ll be the end of him,’ says Tavo, with tears. ‘The way I see it, his life got three outcomes: get killed by the cops or a rival gang for thinking he’s a gang member (which he’s not), join a gang because it’s what’s left to protect himself and I’ll kill him, or flee the country and hope for the best.’

Tavo kicks the artisanal soldered pipe bike over and hits his chest with a calloused fist covered in mortar flakes, the other hand gripping my shoulder. ‘I’m a simple farmer, mijo. I have my corn, I have my house, and I have my kids. My hands been worked raw and I’m tired of fighting. Fighting to not starve, fighting for my kids. But if I tell you the truth, I think Honduras left old shits like me behind, and started eating its young.’ Tavo piously clasps his hands in a plea, he looks at the storm above. ‘I can only ask god to have clemency on my Moisa.’ Moises would leave the neighborhood soon after, without telling a soul.”

—Tomas Ayuso

San Pedro Sula, Honduras, August 2017.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-006

Dario’s crescent scar curves from his temple to his jawbone and serves as a reminder. As a child, a police officer mistook him for a lookout and pistol-whipped him. He was another child brutalized in the name of pacification. Wave after wave of crackdowns left the young Dario traumatized and vindictive. Fed up, he chose to join a gang.

San Pedro Sula, Honduras, August 2017.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-007

First as lookouts and later as full-fledged gang members, neighborhood children are groomed at a young age by their brothers, cousins, and neighbors. The slow process of recruitment into gangs is often the only viable option, as communities have little in the way of alternatives for abandoned young people with nothing to lose.

San Pedro Sula, Honduras, August 2017.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-008

Chino (left) and Tito (right), the lookouts, take shelter from the unrelenting San Pedro heat. They lie on beds in houses rendered vacant by gang fighting. Without their weapons, their radios, and their scowls, these fearsome boys from San Pedro are not unlike any other child their age. They play ball, get shy around girls, and fixate on Madrid vs. Barcelona soccer matches across the Atlantic.

The maras (gang), of which these boys belong to the most extremist wing, espouses a militant ideology that does not have an off switch; its members are expected to be on duty until the morgue takes them. Because of high mortality rates, the recruitment age has become younger. Chino joined at 14 years old and receives the privileges that come with being in active duty: respect, fear, and power. Chino grew up in a broken home but now has followers like Tito, who one day hopes to be like him.

San Pedro Sula, Honduras, August 2017.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-009

Moises (left) and Jaime (right) sit atop a hill in their neighborhood to daydream of a future far from the tension of the streets. A half-decade of peaking violence has carved up San Pedro Sula, its low-income districts enduring the harshest scars. Though clashes between gangs and police remain, the persistent top-down pressure of corruption and economic dispossession continues to fray communities, and particularly young people, who live along the periphery of Honduras’ second largest city.

San Pedro Sula, Honduras, August 2017.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-010

Ervin and Orlando, neighbors back home in Honduras, look at the 2,000-mile journey ahead of them. Ervin long feared Mexico; his mother had vanished while traveling through there a decade earlier. In hopes of finding his mother, he’d ask people who’d been there before: “Did you ever come across Marian from Choloma, with long brown hair and great big eyes?”

Tenosique, Mexico, March 2015.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-011

Nico made a brutal decision by choosing to flee rather than join a gang. He clutches a fantasy close to his chest as motivation while on his journey: “I want to become a doctor, I want to be a good man. I want to fight evil in my country, and all of Central America.”

Arriaga, Mexico, March 2015.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-012

This group of men were separated from their families during a midnight raid by border police. They hid sleeplessly in alleys, and pits of waste. Before continuing into the Oaxacan hinterlands, the group’s leader pleaded on behalf of displaced peoples: “We follow a dream. Not a criminal dream but a dream of life. And for this we’re hunted.”

Arriaga, Mexico, July 2015.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-013

“I've been robbed, beaten for my money and shoes. Still, I thank God: As long as there is life and hope, I’ll have what matters.” Israel jumps between cars just as the beastly freight train rouses from its slumber and lurches forward on its journey towards the United States–Mexico border.

Arriaga, Mexico, July 2015

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-014

“‘Nothing to do but rest and wait for the next train.’ Jimmy was from the same neighborhood as me. He was attempting to cross into the United States again after having gone back home to Honduras to bury his long-ailing mother. He had been her only son, and she was the reason he’d left home half a decade ago.” —Tomas Ayuso

Amatlan, Mexico, April 2017.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-015

“‘I can't go home,’ he says. He is a marked man. I show him his portrait and he weeps. He had escaped gang life and hadn’t seen a picture of himself in years: ‘I can't believe what my life’s become. I stay awake at night filled with anxiety. I’m not a bad man, I never had a choice.’ On his chest a tattoo reads ‘catracho,’ slang for Honduran.” —Tomas Ayuso

Celaya, Mexico, March 2017.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-016

Marcio, 16 years old, takes his shoes off for the first time in days. Exhausted and despondent, he was unsure whether to continue enduring the horror of traveling. “There are monsters out there, and I’m all alone! Whenever I find shelter, I cry myself to sleep. I lay awake worried my mom might never hear from me again if I were to disappear.”

Celaya, Mexico, March 2017.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-017

“I asked him: ‘What do you see, brother?’ Reverently and transfixed, he said, ‘The dream, brother.’” —Tomas Ayuso

Left: A young man in a rough border town looks over a security wall into Texas.

Right: The natural border between Mexico and Texas.

Reynosa, Mexico, February 2015.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-018

The boys walk through their neighborhood after football practice. Working as footballers for hire, they stick together through thick and thin. Sharing both struggle and opportunity, they’ve made their space at the edge of the megalopolis.

Mexico City, Mexico, July 2017.

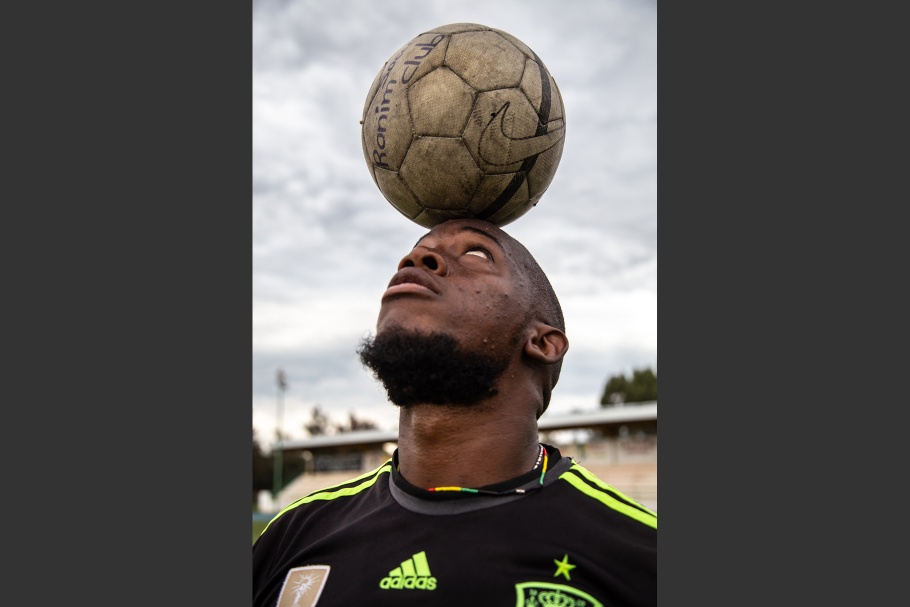

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-019

Misael imposes his will on the pitch against Mexican defenders. He out-maneuvers the rival team and blasts a banger into the back of the net. His team celebrates an early lead as the crowd erupts in xenophobic howls.

Mexico City, Mexico, July 2017.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-020

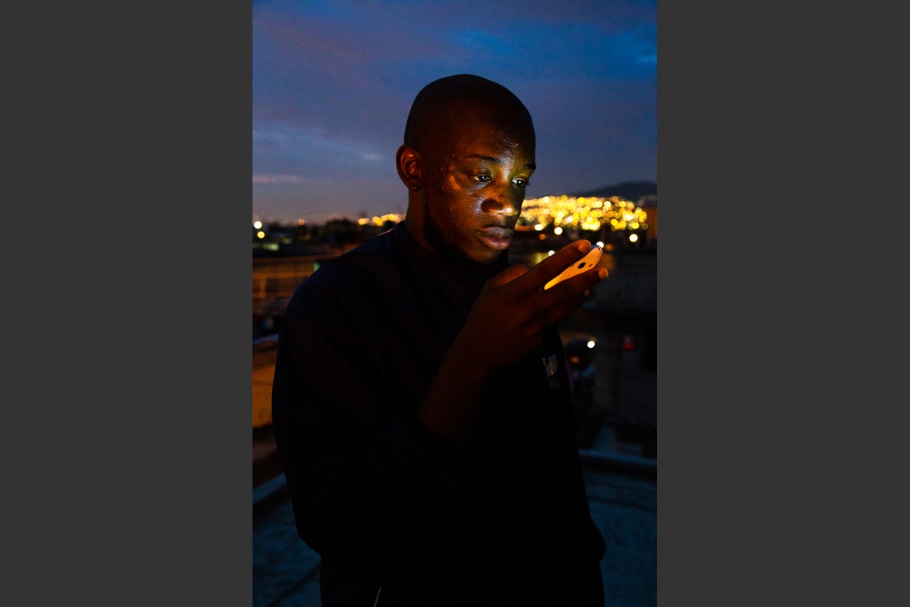

Theo was the first of the boys to make it to Mexico City, foregoing the American dream and choosing to make life in Mexico viable. He misses home, its coast, and culture, but in Mexico he’s earned a second chance at being alive.

Mexico City, Mexico, July 2017.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-021

A cross is wired to the exposed rebar atop the boys’ apartment building to invoke the lord’s protection. Despite living in a rough and tumble neighborhood plagued by many of the issues they fled from in La Ceiba, Honduras, they’ve managed to find peace and family.

Mexico City, Mexico, July 2017.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-022

Theo’s dog tags carry essential information in case something were to happen. Anchored at the bottom is a forlorn message: “MISS U MOM.” Theo doesn’t fear life in exile because he believes that in death he’ll be reunited with his mother who left him far too soon.

Mexico City, Mexico, July 2017.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-023

Duvan speaks to his parents back home via FaceTime. He has just arrived in Mexico with the help of Theo who took him in. After surviving the journey, Duvan could barely contain his excitement. He told his mother just how different Mexico is as she repeated, “Thank God, thank God, thank God.”

Mexico City, Mexico, July 2017.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-024

With varying demanding schedules to sustain themselves, the boys relish any time they’re able to spend together. They talk about love, life back home, and their futures. Through the process of surviving, the boys have become brothers.

Mexico City, Mexico, July 2017.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-025

With cicadas loud in the summer air, the border defense militia, Free Nebraska, begins its watch over the Rio Grande. A member of the militia stands on a river bend on the Texan side, opposite a pine forest in Northern Mexico. There, he waits to intercept any would-be border crossing individuals.

Los Ebanos, United States, August 2015.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-026

Recently the Rio Grande Valley became a common point of unauthorized entry into the United States. After traveling thousands of kilometers through mountains, jungles and deserts, migrants swim across the turbulent river to reemerge on land they’ve long dreamed of but never seen.

Los Ebanos, United States, August 2015.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-027

In this border town, recently arrived people use this cemetery to hide among Christian statues and century-old graves after crossing the Rio Grande. After being displaced, traveling, and crossing the border’s water, they reach America and their life in the shadows begins immediately.

Los Ebanos, United States, August 2015.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-028

Migrants move quickly and cautiously to get as far away as possible from the border, and into their diaspora’s communities in cities across the country.

Los Ebanos, United States, August 2015.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-029

But before truly arriving into the United States, the final migration checkpoints lie inland along northward highways, such as the known checkpoint near Falfurrias, an hour from McAllen, Texas.

Falfurrias, United States, August 2015.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-030

After crossing the final security impasse 100 miles from the border and having survived the thousands of different threats against their lives at home and in exile, displaced people’s right to grow old becomes theirs once more.

Falfurrias, United States, August 2015.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-031

Theo searches for a mobile signal on his rooftop, the electric glow of Mexico City behind him. He asks his estranged family for help to make rent. They refuse. He’ll find a way to pay the landlord with the help of his new chosen family, “Los Boys,” a group of young men from La Ceiba, Honduras, who live together on the outskirts of Mexico City. They had fled the surging violence and dearth of employment opportunities back home and had planned to seek asylum in the United States. But after surviving the harrowing migrant route through southern Mexico and hearing of anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States, they chose to stay in Mexico and earn a living as talacheros, footballers-for-hire in Mexico’s regional football leagues.

Mexico City, Mexico, July 2017.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-032

Away from the clamor on the streets and the pressure of the block, Moises escaped to his spot on a hill above the barrio below. He weighed his options: stay, join a gang, or leave. He reckoned his life was at risk regardless of what he did. With his child on the way and a spike in violence in San Pedro, he decided he would abandon Honduras, as his generation does every day. When the right to grow old isn’t guaranteed, the fight to make it so becomes the only struggle that matters.

San Pedro Sula, Honduras, August 2018.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-033

Orlin lived in Tampa for 10 years doing construction until he was deported to Honduras, without a way back to his family in Florida. While attempting to cross Mexico, he was beaten and tortured by criminals who prey on migrants. Yet, still, he refuses to give up, as his life all but stopped the moment he was separated from his family. “My wife and little girl are my world and every day we’re apart is a day of my life I lose.”

Tenosique, Mexico, April 2017.

20180925-ayuso-mw25-collection-034

“Karla wore a hat for her picture. ‘It’s my brothers, and I want him to see it.’ He had gone missing in Mexico a few weeks prior. It was pained wishful thinking, I thought. I snapped away and had a long chat next to her mother’s comal (“griddle”). Some months later, Karla’s brother would re-emerge and la hermanita (“little sister”) was able to share the picture with her beloved older brother.” —Tomas Ayuso

San Pedro Sula, Honduras, April 2018.

Tomas Ayuso (b. 1986, Guatemala; lives in the Americas) is a Honduran photojournalist. His work focuses on Latin American conflict as it relates to the drug war, forced displacement, and urban dispossession.

Ayuso seeks to bind the disparate threads of communities into the grand interlinked story of the Americas. In covering the different types of violence facing the region’s people, Ayuso hopes to create a record of both continental struggles and local successes.

Ayuso holds an MA in conflict and development from the New School (2012), and is an International Reporting Project Fellow (2016) and a National Geographic Portfolio Grant recipient (2017).

Tomas Ayuso

Triggered by a decade of violence, corruption, and scarcity, Hondurans are fleeing collapsing communities toward perceived shelter across borders at the rate of hundreds per day. This project renders visible the man-made catastrophe of forced migration of a people who refuse to be dehumanized.

Set in Honduras, Mexico, and the United States, this work tracks the vulnerabilities that displaced people face before and after crossing borders and reflects on Honduran identity as it endures the crossing of both physical and internal boundaries. It attests to the fight to preserve life as an act of resistance in itself: migration as a means of survival.

In countless at-risk communities across Honduras, along the migrant route to the United States, and among the far reaches of the recent diaspora are stories that capture the sources and impact of migration. These stories convey what it is like to experience a journey rife with risks and toward potentially hostile destinations.

This work is made with love for my fellow Hondurans as well as indignation about their fate as they fight for their right to grow old.

—Tomas Ayuso, September 2018