20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-001

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

Minarsih, an Indonesian domestic worker, laughs during a Mother’s Day celebration at Bethune House Migrant Women’s Refuge in Hong Kong. She has a six-year-old son in Indonesia. In 2014, Bethune House accommodated more than 600 migrant women.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-002

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

Erwiana Sulistyaningsih, center, leaves the sentencing hearing for her former employer Law Wan-tung. Wan Chai, Hong Kong, February 27, 2015.

In a lawsuit that received international attention, a judge sentenced Law to a six-year prison term for grievous bodily harm, assault causing actual bodily harm, common assault, and four counts of criminal intimidation. Found guilty of 18 out of 20 counts of abuse of Sulistyaningsih and two other domestic workers, Law was also fined 15,000 Hong Kong dollars (1,930 U.S. dollars) for failing to pay wages or grant Sulistyaningsih days off. Law physically, mentally, and psychologically abused Sulistyaningsih for eight months. She was beaten, underfed, and didn’t receive wages, and her health deteriorated so much that she was eventually unable to walk. Her employer threatened to hurt her family in Indonesia if she told anyone about the abuse and took her to the airport to send her back to Indonesia. There, another Indonesian traveler noticed her and helped her.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-003

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

Migrant workers wait for their flight to the Philippines at Hong Kong International Airport. Hong Kong, January 2, 2017.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-004

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

At weekly sharing sessions at Bethune House Migrant Women’s Refuge in Hong Kong, residents update one another about their court cases and plans for the week. Most domestic worker abuse cases last about a month and often end when the domestic worker decides to drop her case and return to her home country. While the cases are pending, the women are not allowed to work, so they have to rely on charities for food, shelter, and emergency needs such as visas, medical expenses, bail money, and transportation to court.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-005

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

A domestic worker cleans a window inside her employer’s home in Hong Kong. Domestic workers in Hong Kong are often vulnerable to labor trafficking and exploitation.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-006

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

A portrait of Erwiana Sulistyaningsih before the sentencing hearing for former employer Law Wan-tung. Wan Chai, Hong Kong, February 27, 2015.

In a lawsuit that received international attention, a judge sentenced Law to a six-year prison term for grievous bodily harm, assault causing actual bodily harm, common assault, and four counts of criminal intimidation. Found guilty of 18 out of 20 counts of abuse of Sulistyaningsih and two other domestic workers, Law was also fined 15,000 Hong Kong dollars (1,930 U.S. dollars) for failing to pay wages or grant Sulistyaningsih days off. Law physically, mentally, and psychologically abused Sulistyaningsih for eight months. She was beaten, underfed, and didn’t receive wages, and her health deteriorated so much that she was eventually unable to walk. Her employer threatened to hurt her family in Indonesia if she told anyone about the abuse and took her to the airport to send her back to Indonesia. There, another Indonesian traveler noticed her and helped her.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-007

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

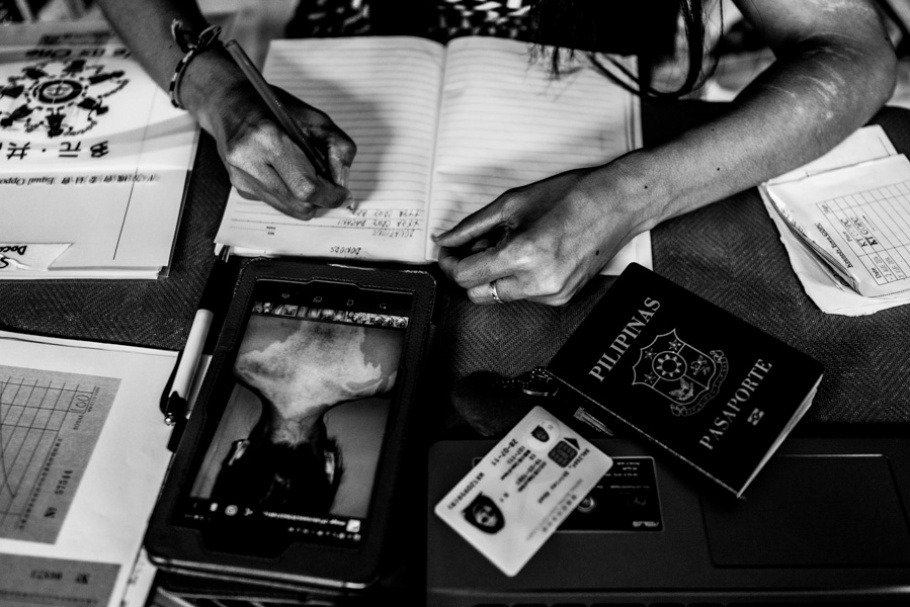

Shirley Dalisay, 31, from the Philippines, prepares her documents for her case against her employer. Dalisay suffered from burns on her back and arms when a pot of boiling hot soup fell on her after her employer “accidentally” put the soup above the shoe rack where she stored her shoes.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-008

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

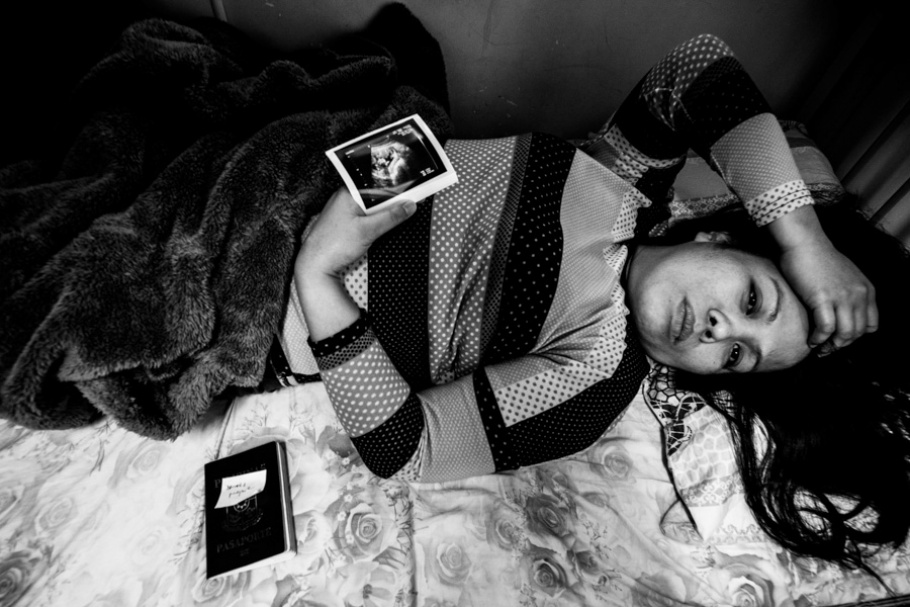

Lilibeth, a domestic worker in Hong Kong who is originally from the Philippines, holds an ultrasound image of her unborn child. She was fired when she asked for maternity leave pay, a payment granted by law. In a statement to police, she said her employer illegally kept her passport and then tore it up so that she could not travel.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-009

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

Aniya checks her reflection with her friend Judy. Aniya was forced by her employer to work in China without proper food, rest, or salary. She cannot read or write. She is now back in Indonesia.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-010

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

Queenie, a Filipina domestic worker, holds her seven-day-old baby, Yuan. When Queenie learned that she was pregnant, she asked her employer to allow her to return to the Philippines. The next day, the police arrived at her workplace and told her that her employer had accused her of stealing an earring. She was ultimately convicted of that crime and sentenced to imprisonment. Queenie believes that her employer wanted to avoid paying for her maternity leave. Prison authorities brought her to a hospital to deliver her baby, who was born on January 1, 2015. Since she had already served out her sentence, she was released from custody a few days later. With nowhere to go, Queenie ended up at the Kowloon Union Church, where a minister saw her crying. She was referred to Bethune House Migrant Women’s Refuge in Hong Kong for shelter and aid.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-011

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

Shirley calls her family back in the Philippines while Sunarwi, an Indonesian migrant worker, prays inside Bethune House Migrant Women’s Refuge. Hong Kong, December 9, 2014.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-012

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

Shirley speaks with her husband Edgar Calwing inside Bethune House Migrant Women’s Refuge. Her husband is also a migrant worker in Taiwan. Their four-year-old child is in the care of their parents in the Philippines. Hong Kong, August 26, 2014.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-013

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

Daisy attends a human trafficking event after mass at Saint James Church in Queens. Queens, New York, July 06, 2015.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-014

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

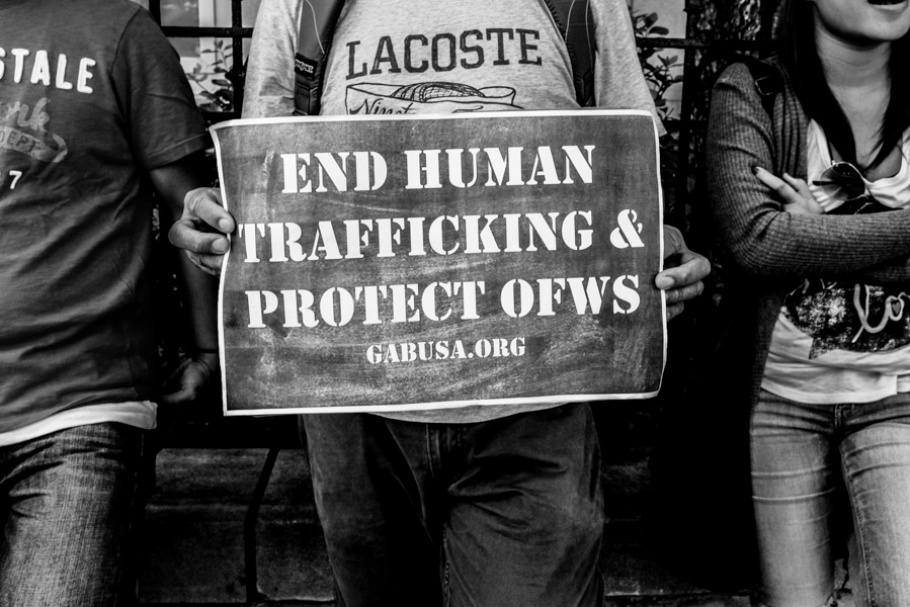

Members of F15, a group of Filipino trafficking survivors, join a rally in New York for Philippines Independence Day. New York, New York, June 8, 2015.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-015

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

Cecil Delgado (left), a member of F15, a group of Filipino trafficking survivors, speaks with other survivors at a rally held in New York for Philippines Independence Day. New York, New York, June 8, 2015.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-016

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

Cherry intended to work in the United States as a teacher but ended up being trafficked instead. She was forced to clean houses to pay for food and lodging. After running away and fighting for her rights, she now works as a teacher in Brooklyn.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-017

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

Daisy Benin inside her employer’s home in New York. She has been working as a nanny for the family after having run away from her traffickers.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-018

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

Members of F15, a group of Filipino trafficking survivors, during barbecue night in Jersey City, New Jersey. Trafficking survivors work to have normal lives despite what they have gone through.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-019

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

Daisy doing her current employer’s laundry. She arrived in the United States seven years ago and was told by her recruiter that she would be working at the Grand Plaza Hotel in Branson, Missouri. Instead, her recruiter took her to work in Panama, Florida. New York, New York, June 27, 2015.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-020

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

To save money in hopes of seeing her children, Ms. Santos lives in a small bedroom in Queens. She has filled her walls with photographs of her children.

20170925-bacani-mw24-collection-021

From the series Modern Slavery, 2014–present.

Judith Dalauz having dinner with her children in their Queens apartment. She came to New York in 2005 to work as a domestic employee for a Japanese diplomat’s family. She was promised a $1,800 per month salary with benefits, but was forced to work 18 hours a day for less than $500 a month. Dalauz had been separated from her children for almost a decade, but was reunited with them in March 2015 when her four children arrived in the United States. Queens, New York, July 25, 2015.

Xyza Cruz Bacani (Filipino, b. 1987) is a street and documentary photographer based in Hong Kong who uses her work to raise awareness about underreported stories. Having worked as a second-generation domestic worker in Hong Kong for almost a decade, she is particularly interested in the intersection of labor migration and human rights. She is currently working on her global project Modern Slavery, two chapters of which have been published in the New York Times Lens blog and other publications.

She is a Magnum Foundation Photography and Human Rights Fellow (2015), and a grantee of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and the WYNG Media Award Commission (2017). The Open Society Moving Walls Grant will support a new body of work on the role of education in promoting peaceful coexistence amidst armed conflict in Mindanao, Philippines.

Xyza Cruz Bacani

According to the United Nations, there were 244 million international migrants in 2015. Three out of every four people who migrate across international borders do so for employment. Yet once abroad, many of these labor migrants—tens of millions—only find low-paying, temporary, and informal work.

Migrant workers are like air, invisible but necessary. Although vital to the socio-economic success of society, they are often treated as lower-class minorities. In many countries, labor migrants are unprotected by local labor laws and vulnerable to exploitation by employers. In extreme cases, they fall victim to trafficking. Having been promised high-paying jobs or other appealing opportunities by recruiters, employers, or contractors, they end up in abusive or exploitative situations through force, fraud, or coercion.

For the past few years, I have used photography to magnify the voices of various labor trafficking survivors—from teachers to managers to domestic workers—in a variety of cities across the globe. The photographs in this exhibition feature survivors in Hong Kong and the New York metropolitan area.

I aim to challenge the stigma and stereotype of “helpless” victims, by focusing on the daily lives of survivors and highlighting those who take great risks to escape exploitation and speak out against the abuse they and others have endured. By joining protests and sharing their experiences, these survivors spread awareness and encourage others to seek help and fight for justice.

—Xyza Cruz Bacani, October 2017