19990301-kuwayama-mw02-collection-001

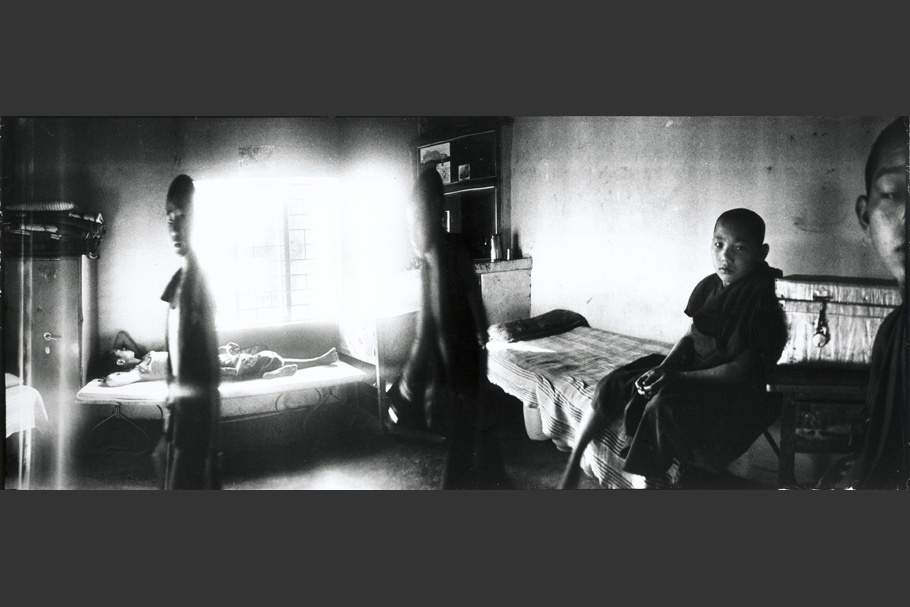

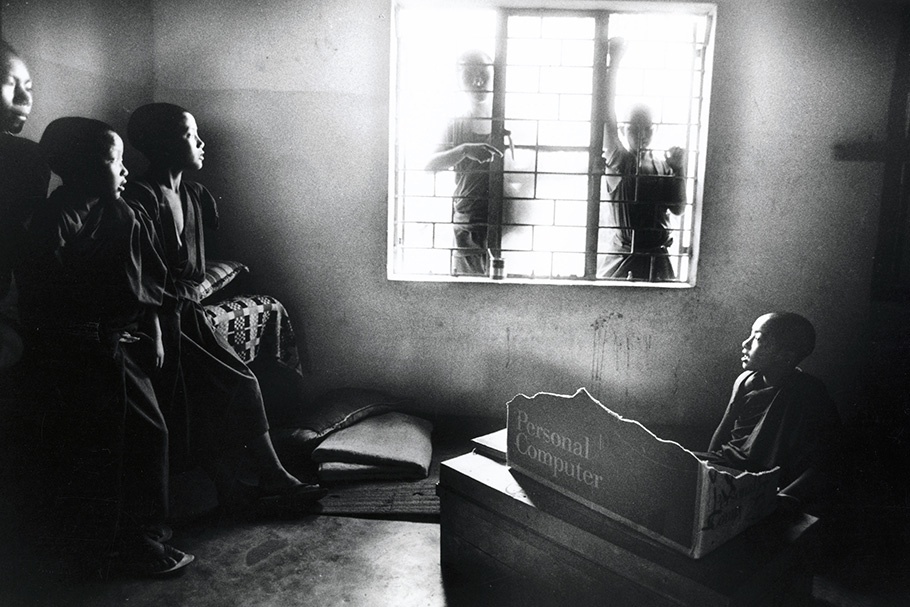

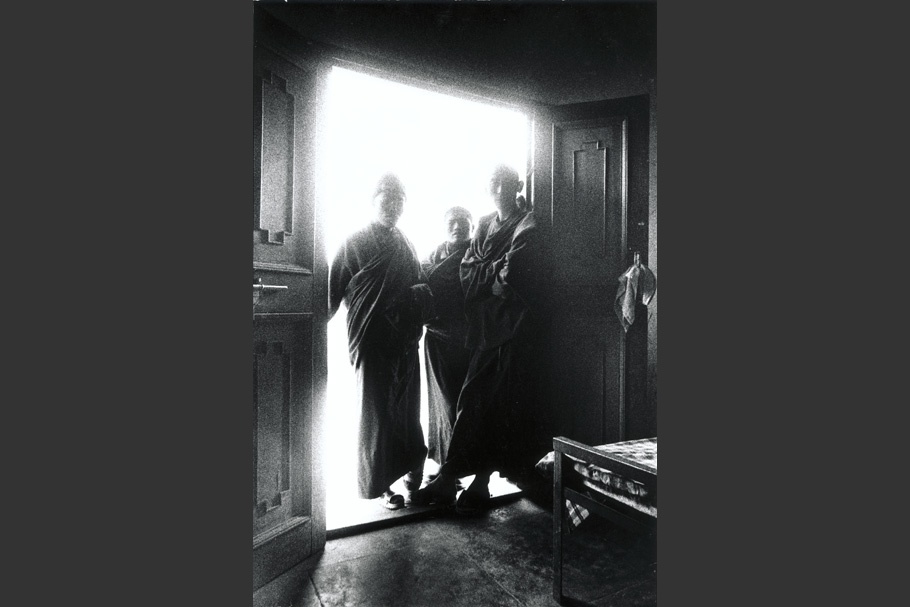

Bylakuppe Tibetan refugee settlement, in the state of Karnataka in southern India. Bylakuppe is home to more than 10,000 Tibetan refugees, including thousands of Buddhist monks and several major Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, including Sera Je and Sera Me, which were named after significant monasteries in the Tibet Autonomous Region, which was occupied by China in 1949.

Circa 1999-2000.

19990301-kuwayama-mw02-collection-002

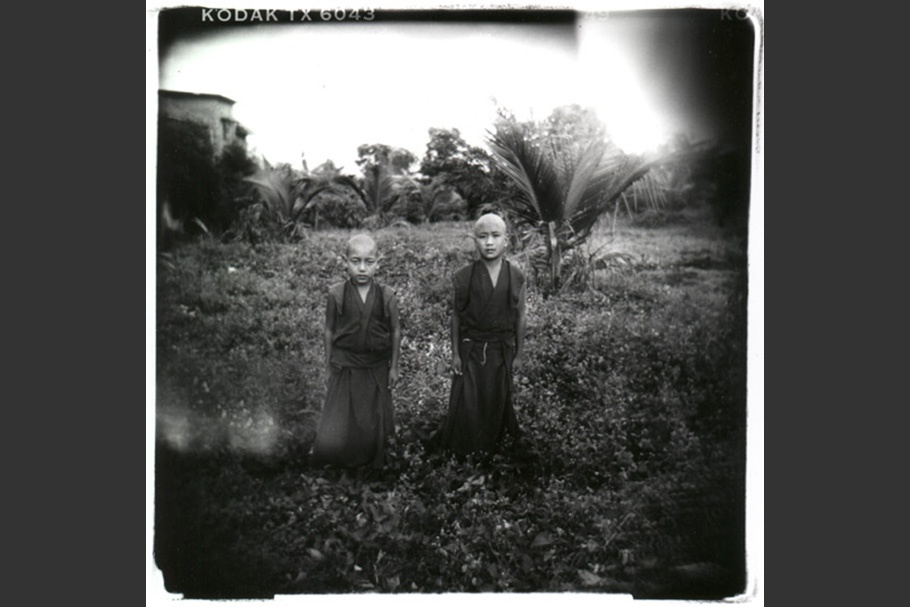

Bylakuppe Tibetan refugee settlement, in the state of Karnataka in southern India. Bylakuppe is home to more than 10,000 Tibetan refugees, including thousands of Buddhist monks and several major Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, including Sera Je and Sera Me, which were named after significant monasteries in the Tibet Autonomous Region, which was occupied by China in 1949.

Circa 1999-2000.

19990301-kuwayama-mw02-collection-003

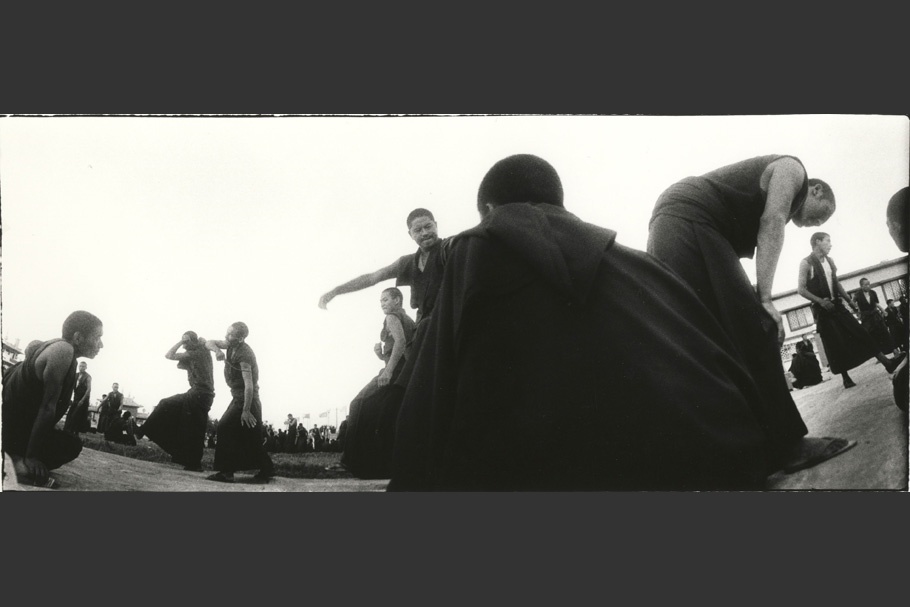

Bylakuppe Tibetan refugee settlement, in the state of Karnataka in southern India. Bylakuppe is home to more than 10,000 Tibetan refugees, including thousands of Buddhist monks and several major Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, including Sera Je and Sera Me, which were named after significant monasteries in the Tibet Autonomous Region, which was occupied by China in 1949.

Circa 1999-2000.

19990301-kuwayama-mw02-collection-004

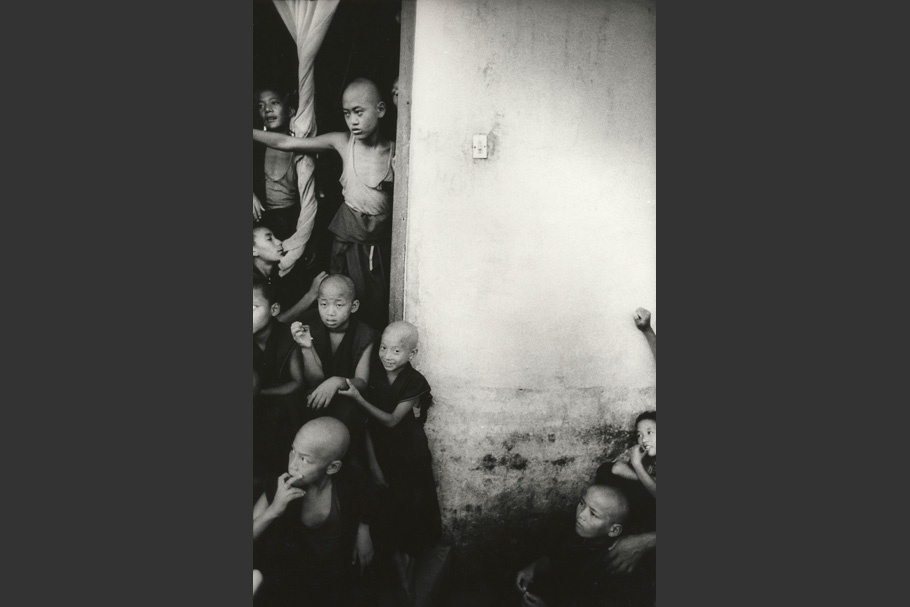

Bylakuppe Tibetan refugee settlement, in the state of Karnataka in southern India. Bylakuppe is home to more than 10,000 Tibetan refugees, including thousands of Buddhist monks and several major Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, including Sera Je and Sera Me, which were named after significant monasteries in the Tibet Autonomous Region, which was occupied by China in 1949.

Circa 1999-2000.

19990301-kuwayama-mw02-collection-005

Bylakuppe Tibetan refugee settlement, in the state of Karnataka in southern India. Bylakuppe is home to more than 10,000 Tibetan refugees, including thousands of Buddhist monks and several major Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, including Sera Je and Sera Me, which were named after significant monasteries in the Tibet Autonomous Region, which was occupied by China in 1949.

Circa 1999-2000.

19990301-kuwayama-mw02-collection-006

Bylakuppe Tibetan refugee settlement, in the state of Karnataka in southern India. Bylakuppe is home to more than 10,000 Tibetan refugees, including thousands of Buddhist monks and several major Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, including Sera Je and Sera Me, which were named after significant monasteries in the Tibet Autonomous Region, which was occupied by China in 1949.

Circa 1999-2000.

19990301-kuwayama-mw02-collection-007

Bylakuppe Tibetan refugee settlement, in the state of Karnataka in southern India. Bylakuppe is home to more than 10,000 Tibetan refugees, including thousands of Buddhist monks and several major Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, including Sera Je and Sera Me, which were named after significant monasteries in the Tibet Autonomous Region, which was occupied by China in 1949.

Circa 1999-2000.

19990301-kuwayama-mw02-collection-008

Bylakuppe Tibetan refugee settlement, in the state of Karnataka in southern India. Bylakuppe is home to more than 10,000 Tibetan refugees, including thousands of Buddhist monks and several major Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, including Sera Je and Sera Me, which were named after significant monasteries in the Tibet Autonomous Region, which was occupied by China in 1949.

Circa 1999-2000.

19990301-kuwayama-mw02-collection-009

Tibetan monks at the Tibetan Refugee Reception Center (TRRC) at Ichangu, Nepal, near Kathmandu. The TRRC is generally the first point of arrival for Tibetan refugees who have successfully crossed the Tibet-Nepal border, and they are registered by UNHCR before continuing onwards, usually to refugee settlements in India.

Circa 1999-2000.

Teru Kuwayama attended the State University of New York at Albany from 1988 until 1993. He learned photography with Michael Ackerman at a student collective called Photoservice. His first published photographs were in the international punk fanzine Maximum Rock n' Roll. He began working as a contributing photographer to Life magazine in 1998. In the same year, he exhibited his photos of New York City’s hardcore punk scene at CBGB's 313 Gallery. In 1999, he received an award from the Alexia Foundation for World Peace to support his work on the Tibetan refugee diaspora.

Teru Kuwayama

In 1959, the Dalai Lama and thousands of his followers fled Chinese-occupied Tibet and established a government in exile in neighboring India. In the face of continuing repression and decimation of their country and culture, communities scattered across India. Now, a generation has been born and raised there, living in stateless limbo, in an intensely alien environment.

In 1997 and 1998, I visited the Tibetan settlements of Dharamsala, home of Bylakuppe, the first of the Tibetan government-in-exile in southern India. I also visited the monastic communities, the most visible symbol of Tibetan culture. The monastic tradition has flourished in India, its population growing each year as new refugees make the dangerous journey across the Himalayas.

Many of these new arrivals are children. According to a tradition that continues today, Tibetan families each send a son to join the monastery, even if it means sending them thousands of miles away, and never seeing them again.

These photographs, I hope, are a testament to the struggle of the Tibetan people, their resourcefulness and grace, and their sheer will to endure. Armed with nothing else, they have survived a genocidal onslaught. In exile, they are dependent on the hospitality of a country that cannot feed its own people.

They rely on the recognition and support of the international community, for if the world forgets them, they are lost.

—Teru Kuwayama, spring 1999